The floodlights at Bears Stadium cut through the November fog like beacons in a coal miner’s dream, illuminating a field scarred by cleats and ambition. On the sidelines, where Travis Turner’s booming commands once echoed like thunder rolling off the Cumberland Plateau, stood a huddle of teenagers—helmets clutched like talismans, eyes fierce with a mix of grief and grit. Union High School’s Bears had just dismantled their rivals from Gate City, 28-14, in the Region 2D semifinals, extending their season to a perfect 12-0. The crowd of 2,500, bundled against the mountain chill, erupted in a chant that shook the rickety bleachers: “Bear Pride! Bear Pride!” But as the final whistle blew, senior quarterback Eli Jenkins dropped to one knee at midfield, his voice cracking over the din into a portable mic. “Coach Turner… wherever you are, we’re trying our best to make you proud. Please come back. We need you.”

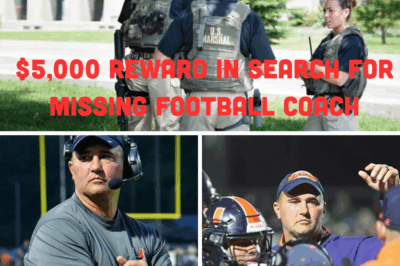

The plea, raw and unscripted, hung in the crisp air—a desperate postcard tossed into the abyss where their 46-year-old mentor had vanished nearly two weeks prior. Travis Turner, the towering architect of this undefeated juggernaut, had slipped into the laurel-choked woods behind his Appalachia home on November 20, a Glock 19 tucked in his waistband and the weight of unthinkable accusations pressing on his broad shoulders. Now, as the U.S. Marshals Service dangled a $5,000 reward for tips leading to his arrest, the Bears marched on without him, their victories a bittersweet symphony of loyalty and loss. In this forgotten corner of Virginia’s coalfields, where football is salvation and secrets fester like black lung, a team’s unbroken streak has become both tribute and torment: proof that the lessons of a fallen hero endure, even as the man himself remains a ghost.

Big Stone Gap clings to the edge of Wise County like a miner’s cap to a helmet—rugged, resilient, and riddled with veins of history both proud and painful. Nestled in the Powell Valley, 400 miles southwest of Richmond, this town of 5,300 souls was once the beating heart of Appalachian coal country, its hills stripped bare for the black gold that fueled America’s industrial roar. The 1980s bust left scars deeper than any dragline: shuttered shafts, opioid shadows, and a youth exodus that hollowed out Main Street. But come Friday nights, the hollows fill with hope. Bears Stadium, a concrete coliseum etched with the ghosts of glory seasons, becomes a cathedral where the faithful gather to exorcise the week’s woes. Union High, a brick-and-mortar bastion enrolling 400 students from clapboard homes and trailer parks, has long been the town’s North Star. And Travis Turner? He was its unwavering flame.

Born in 1979 to Tom Turner, a Hall of Fame coach whose quarterback whispers had sculpted legends at Appalachia High, Travis inherited the family fire like a blood oath. A lanky kid with a cannon arm, he slung passes through high school defenses that couldn’t touch him, earning a scholarship to the University of Virginia’s Wise campus. There, amid the haze of mountain mornings, he bulked up to 235 pounds of coiled muscle, majored in physical education, and dreamed of a life turning boys into men. By 2011, at 32, he planted his flag at Union High as head coach and PE teacher, transforming a middling program into a dynasty. Three region championships, a state semifinal in 2023, and an undefeated regular season this fall—his ledger read like scripture. “Coach didn’t build a team,” said junior lineman Caleb Mullins, his drawl thick as sorghum. “He built brothers. Taught us that every snap’s a second chance, no matter how deep the hole.”

Turner’s sideline persona was pure theater: a 6-foot-3 bear of a man in purple-and-gold polos, veins bulging during two-minute drills, his gravelly sermons blending Sun Tzu with Sunday school. Practices started at dawn on dew-slick fields, ascending Black Mountain for hill sprints that tested lungs and legacies. Film rooms glowed late into the night, where he’d pause plays to dissect not just footwork, but fortitude: “Pain’s temporary, quitters eternal.” Off-field, he was the glue—organizing youth camps for at-risk kids, plowing snow from widows’ driveways, and hosting fish fries where boosters swapped stories over catfish and hushpuppies. Married to Leslie Caudill since 2005, they raised three children in a neat rancher on the fringe of Appalachia, a hamlet of 1,700 where the Clinch River murmurs secrets to the willows. Leslie, a bookkeeper with a smile like morning light, was his quiet co-pilot; their home echoed with the clatter of cleats and the strum of Travis’s old guitar, crooning Merle Haggard on porch swings.

The 2025 season dawned like a revival. The Bears opened with a 42-7 rout of Twin Springs, Jenkins threading needles through defenses like his coach had taught. By October, they were 8-0, Turner’s schemes—a Wing-T hybrid laced with misdirection—leaving opponents grasping at shadows. The town buzzed: tailgates at the Wooden Spoon Cafe spilling onto sidewalks, purple streamers whipping from pickup mirrors. Travis, ever the showman, led pre-game huddles with a ritual prayer: hands stacked, eyes closed, invoking “strength for the fight, grace for the fall.” No one saw the storm clouds gathering. Whispers in the hollers spoke of odd hours on his laptop, late-night drives that veered toward Norton motels. But in Big Stone Gap, heroes don’t harbor horrors; they hoist trophies.

November 18 shattered the idyll. Virginia State Police swarmed Union High like a nor’easter, badges glinting as they seized devices from Turner’s cluttered office—laptops humming with encrypted files, phones buzzing with silenced alerts. The tip had come months earlier, anonymous from the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children: browser histories veering into the abyss, chats with decoys posing as vulnerable teens. By evening, warrants crystallized the nightmare—five counts of possessing child sexual abuse material, five for using a computer to solicit a minor. Penalties? Up to 50 years per charge, a life sentence in leg irons. Travis, summoned to the Appalachia PD annex for “routine questions,” arrived stone-faced, his F-150 idling like a getaway car.

He never emerged the same. Witnesses glimpsed him striding out at dusk, face drained of color, climbing into the truck and gunning toward home. There, with Leslie stirring chili in the kitchen and the kids lost in homework, he knelt by the safe, withdrawing the Glock—purchased for “home protection” after a rash of break-ins. A hurried embrace, a choked “I love you,” and he was gone, boots crunching gravel toward the treeline. The woods behind the rancher—a tangled maze of rhododendron and ridge rock, part of the Jefferson National Forest—swallowed him whole. Leslie, pacing by 9 p.m., dialed 911: “He’s not right. Said somethin’ about ending it all.” Searchers mobilized at midnight: K-9s snuffling trails, drones whirring infrared arcs, volunteers from the Powell Valley Rescue Squad hacking briars by headlamp. Nothing. No boot prints in the mud, no glint of steel in the understory.

Dawn brought the deluge. Warrants unsealed, Turner’s name scorched across WVVA headlines: “Bears Coach Flees Felonies.” Wise County Schools yanked his bio from the website, placing him on indefinite leave—”no contact with students or property.” The FBI looped in, their Norfolk forensics team sifting gigabytes: illicit images cached in Tor shadows, solicitations laced with coaching lingo twisted into enticement. No local victims surfaced—small mercies in the minefield—but the probe spiderwebbed to Roanoke clinics and Bristol camps. Community fault lines cracked: at the Dairy Queen, graybeards nursed coffees, murmuring of “long-known rumors,” a former assistant alleging “weird vibes” at sleepovers. Protests flickered—pink-clad moms from Norton demanding audits, signs reading “Safeguard Our Sons.” Yet the field called louder. Assistant coach Harlan “Hank” Whitaker, a burly ex-linebacker with Turner’s schemes tattooed in his brain, took the helm. “Next man up,” he barked at the first practice sans Travis, his voice a pale echo. “That’s what he preached. We live it now.”

The Bears answered. November 22’s quarterfinal against Honaker was a 35-10 clinic: Jenkins, a 6-foot-2 senior with a rocket arm, diced the secondary for 280 yards and four scores, his stiff-arm on a goal-line stand channeling Turner’s fabled “Bear Claw” tackle. The crowd, half in stunned silence, half in defiant roar, waved purple pompoms like war banners. Post-game, the team gathered at midfield, jerseys swapped for hoodies, as chaplain Reverend Amos Hale led a circle: “Lord, for the wanderer, guide his steps. For these boys, steel their hearts.” The semifinals followed on the 29th, that Gate City grinder where Jenkins’ third-quarter bomb to wideout J.D. Hale sealed the deal. As the clock hit zero, the stadium fell hushed; then Jenkins’ mic-drop plea pierced the night, livestreamed to 10,000 viewers on the school’s Facebook. “We try our best to make you proud, please come back.” Tears streaked war paint; boosters sobbed in the stands. By dawn, #ComeBackCoach trended locally, a digital dirge laced with prayers and pleas.

The U.S. Marshals’ entry on December 1 cranked the urgency. Their Western District poster—Travis’s mugshot, brown hair tousled, eyes shadowed like storm clouds—plastered I-64 billboards and Piggly Wiggly bulletin boards. “$5,000 REWARD,” it screamed in block caps, with caveats: “Armed and dangerous. Use extreme caution.” Tips flooded the lines—1-877-WANTED2 humming with cranks (sightings at Kingsport truck stops) and confessions (a cousin’s vague “he’s headin’ west”). Ground teams scoured 20 square miles of Jefferson Forest, ATVs churning mud, bloodhounds baying at phantom scents. Leslie, hollow-cheeked at the First Baptist prayer vigil, offered only whispers: “He’s hurting. Pray he finds peace.” The kids, shuttled to kin in Norton, skipped school for counseling, their silence a shield against the town’s prying eyes.

Yet amid the manhunt, the Bears’ streak gleams like fool’s gold—a 12-game skein unbroken, state semifinals looming December 6 against Glenvar High in Salem. Whitaker’s tweaks—more no-huddle to honor Turner’s tempo—have the squad humming, but ghosts lurk in every huddle. “Feels like he’s watchin’ from the ridge,” Mullins confided after drills, scanning the treeline. Jenkins, Turner’s handpicked heir, pores over old game tapes, mimicking the coach’s drawl: “Fight like your name’s on it.” The town rallies ’round: Wooden Spoon specials dubbed “Bear Claw Burgers,” boosters wiring $2,000 for travel, a mural on the water tower—purple bear mid-roar, scripted below: “Undefeated in Heart.”

In Big Stone Gap, where coal dust still cakes the lungs and football mends the fractures, Travis Turner’s vanishing is a wound that win or lose, time alone might cauterize. The Bears charge toward a championship he blueprinted, their victories a defiant hymn: We endure, we excel, we echo you. But in quiet midfield moments, as frost rims the goalposts and the mountains stand sentinel, the plea lingers—a quarterback’s cry into the void. “Please come back.” For a team, a town, a legacy teetering on the edge of legend and lament, the game’s not over till the whistle—and the wanderer—returns.

News

The Harrowing Search for George Smyth in Romania’s Shadowed Bucegi Mountains

The wind howled through the jagged spires of the Bucegi Mountains like a lament, whipping snow into blinding veils that…

Fractured Field: New Revelations in the Travis Turner Disappearance Shake Virginia’s Heartland

The November frost clung to the chain-link fence surrounding Bears Stadium like a shroud, muting the purple-and-gold banners that once…

US Marshals offering $5,000 reward in search for missing Virginia football coach

In the mist-shrouded hollers of Wise County, where the Appalachian Mountains rise like ancient sentinels guarding secrets too dark to…

Whispers in the Dark: The Unconfirmed Nightmare Haunting the Anna Kepner Cruise Tragedy

The fluorescent hum of the Grove Church’s fellowship hall had long faded, but the echoes of laughter and sobs from…

Shadows on the Horizon: The Chilling Threat That Pierced a Family’s Cruise Nightmare

The fluorescent lights of the Grove Church in Titusville buzzed faintly overhead, casting a sterile glow on a sea of…

Whispers from the Brink: Austin Lynch’s Agonized Plea Echoes Through a Community’s Grief

The sterile hum of fluorescent lights in Stony Brook University Hospital’s ICU ward felt like a cruel metronome, marking time…

End of content

No more pages to load