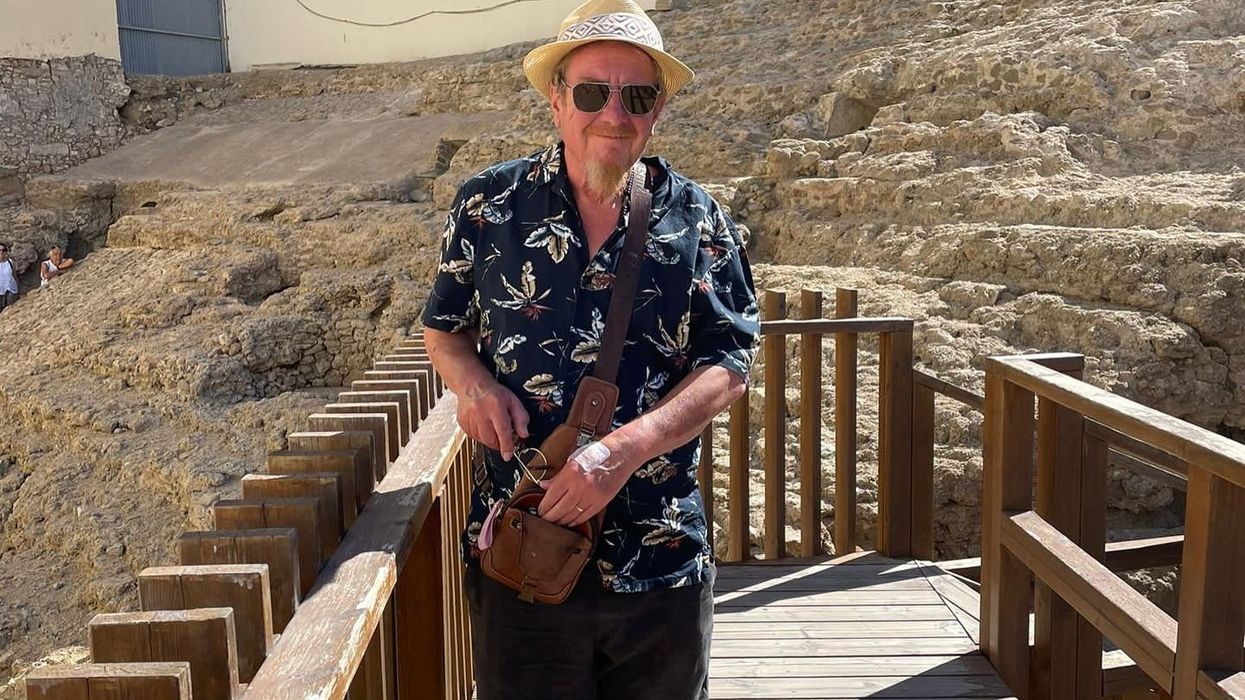

A former high-profile BBC presenter living with Parkinson’s disease claims he was publicly denied boarding-denied by Turkish Airlines staff at London Heathrow because he could not produce an on-the-spot letter from his GP confirming he was “fit to fly.” Passengers looked on in disbelief as the retired broadcaster, visibly shaking from his condition, was told he posed a “safety risk” and would not be allowed on the flight to Istanbul without the document, despite having flown the same route without issue many times before.

The incident, which took place last month at Terminal 2, has reignited fierce debate about how airlines treat passengers with neurological conditions and whether rigid bureaucracy is quietly discriminating against people with disabilities.

The presenter, who spent more than twenty years reading the news on flagship BBC programs and has chosen to keep his name private while legal proceedings are considered, described the episode as the most humiliating experience of his life.

“I was trembling anyway because of the Parkinson’s, but when the gate agent started raising her voice and announcing to everyone around that I might ‘become incapacitated’ during the flight, I felt like the ground disappeared beneath me,” he said. “People were filming on their phones. Children were asking their parents what was wrong with the ‘shaking man.’ I haven’t felt that small since the day I was diagnosed.”

According to the retired journalist, he presented his electronic boarding pass and passport as usual. Everything was normal until a supervisor was called over after he asked for assistance boarding early – a common request for passengers with mobility issues or neurological conditions. What followed was a 40-minute standoff in full view of other passengers.

“They kept repeating that Parkinson’s is a ‘variable condition’ and that can deteriorate mid-flight’ and that new internal policy required a medical certificate dated within ten days of travel,” he explained. “I told them I’ve flown Turkish Airlines a dozen times since diagnosis, including long-haul to Australia, and no one has ever asked for this before. They simply shrugged and said ‘rules are rules.”

A fellow passenger, Sarah Mitchell, 34, from Manchester, witnessed the entire scene. “It was awful,” she said. “He was perfectly polite, well-dressed, clearly not drunk or aggressive; just a gentleman in his late 60s whose hands were shaking. The staff treated him like he was some kind of threat. I heard one of them say loudly, ‘We cannot take the risk if you have a seizure or become incontinent.’ The poor man went bright red.”

Eventually, after heated phone calls and involvement of Heathrow ground staff, the presenter was escorted away from the gate and rebooked onto a British Airways flight the next day, at his own additional expense of nearly £800. Turkish Airlines reportedly refused to rebook or reimburse him because he had been “medically denied boarding.”

Turkish Airlines has a section on its website about passengers with reduced mobility and medical conditions, stating that “in some cases” a medical clearance form (MEDIF) or recent doctor’s letter may be required for certain illnesses. However, Parkinson’s disease is not explicitly listed as one of the conditions that automatically triggers this requirement, and many patients say they routinely fly the carrier without extra paperwork.

Disability campaigners have called the incident yet another example of airlines hiding behind vague “safety” rules to avoid the minor inconvenience of helping disabled passengers.

“It’s bureaucratic ableism dressed up as policy,” said Tom Hendry, policy director at the neurological charity Nerve UK. “Parkinson’s is not epilepsy. Most people with Parkinson’s are perfectly capable of flying. Tremor and stiffness do not make someone a safety risk. Requiring a fresh GP letter every time someone wants to travel is prohibitive; many GPs now charge £30–£50 for such letters and can’t always produce them at short notice.”

He added: “This gentleman is a seasoned traveller who has managed his condition for years. To treat him as if he might suddenly become incapacitated mid-Atlantic is not evidence-based; it’s prejudice.”

The Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) says airlines are within their rights to request medical clearance if they have genuine concern about a passenger’s fitness to fly without assistance, but campaigners argue the rules are applied inconsistently applied and often used as an excuse to offload passengers who might need minor help.

Since the incident, the former presenter has instructed solicitors specializing in disability discrimination. “I spent decades holding powerful people to account on the BBC,” he said. “The irony is not lost on me that, now that I’m the vulnerable one, a corporation can humiliate me in public and claim it’s just following procedure.”

Turkish Airlines issued a brief statement saying: “The safety of our passengers and crew is our highest priority. In certain medical situations, we require documentation to ensure a safe flight for all. We regret any distress caused and are investigating the matter.”

Yet for the retired broadcaster, the damage goes beyond one spoiled trip. “I used to love travel,” he admitted, voice cracking. “Now I’m terrified to book another flight in case the same thing happens again. Parkinson’s already takes so much from you. It shouldn’t take your dignity too.”

As disability advocates are calling for clearer, unified international rules so that people with stable chronic conditions are not subjected to arbitrary gate-side interrogations. Until then, thousands of passengers with Parkinson’s, multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy and similar conditions say they live in fear of being publicly shamed the next time they try to board a plane.

For one of Britain’s once most-trusted voices, a simple journey home for Christmas has become a nightmare he says he will never forget, and a stark reminder that, even in 2025, having an invisible disability can still mean being treated as invisible cargo rather than a human being.

News

The Final Text Emily Finn Sent Her Best Friend Seconds Before Austin Lynch Pulled the Trigger – Long Island’s Thanksgiving Nightmare That Will Never Be Forgotten.

At 11:07 a.m. on the day before Thanksgiving, Emily Finn’s iPhone lit up with a message that would become the…

Emily Finn’s Eerie Final Text to Her Best Friend – The Chilling Warning Her Mother Can’t Stop Replaying in Her Nightmares.

In the quiet hours before Thanksgiving turkey and family laughter filled the air, 18-year-old Emily Finn slipped out of her…

King Charles’s Desperate Midnight Palace Huddle as Harry’s Lawyers Pull the Ultimate Legal Trigger.

In the shadowed opulence of the Belgian Suite, where portraits of stern-faced ancestors seemed to whisper warnings from the walls,…

Ruth Codd’s Gut-Wrenching TikTok Bombshell – The Traitors Star’s Second Amputation That Left Fans in Floods of Tears.

In a video that’s already racked up 2.7 million views and counting, Ruth Codd – the foul-mouthed Irish firecracker who…

Amanda Owen’s Heart-Melting Birthday Post to Ex-Husband Clive Just Broke the Internet – Are Yorkshire’s Most Famous Farmers Secretly Back Together?

Nine little words from Amanda Owen have sent the entire nation into a romantic tailspin. Late last night, as the…

Bradley Walsh Sparks Total Mayhem with Shock Strictly Backstage Visit – Is the BBC About to Drop the Biggest Hosting Bombshell Ever?

Chaos erupted behind the glitterball last Saturday night when Bradley Walsh, grinning like a man who knows something the rest…

End of content

No more pages to load