In the vast, unforgiving expanse of South Australia’s Mid-North outback, where red dust stretches to infinity and the silence is broken only by the occasional bleat of sheep, the disappearance of four-year-old Gus Lamont has cast a long, haunting shadow over a community accustomed to isolation. Today, as search teams reconvene under the relentless sun, a former homicide squad detective has unveiled a chilling theory that injects new urgency—and darker possibilities—into the case. Gary Jubelin, renowned for his relentless pursuit in high-profile missing persons investigations, suggests that young Gus’s fate may involve not just a tragic accident, but potential human intervention or even the predatory dangers of the wild. As police expand their hunt across the sprawling Oak Park Station, Jubelin’s words echo like a warning: the truth may be closer, and more sinister, than anyone dares to imagine.

Gus Lamont, with his mop of curly blond hair, infectious grin, and boundless energy, vanished without a trace on the evening of September 27 from his family’s remote sheep station, Oak Park, located 43 kilometers south of the tiny town of Yunta. The boy, described by loved ones as “cheeky” and “adventurous,” was last seen by his grandmother around 5 PM, playing happily on a mound of red dirt behind the homestead. Dressed in a blue Minions long-sleeved shirt, light gray pants, sturdy boots, and a wide-brimmed gray sun hat to shield him from the harsh outback rays, Gus was the picture of innocent exploration in a landscape that can swallow the unwary whole. His family—mother Jess, one-year-old brother Ronnie, and grandparents Josie Murray and her partner—called him in for dinner just 30 minutes later, only to find him gone. What began as a frantic family search escalated into one of South Australia’s largest ever operations, a testament to the nation’s collective heartache over lost children.

The initial response was swift and monumental. South Australia Police (SAPOL), alongside the State Emergency Service (SES), volunteers, Indigenous trackers, and even the Australian Defence Force (ADF), mobilized hundreds of personnel. Helicopters buzzed overhead with thermal imaging cameras, drones mapped the rugged terrain in high definition, and ground teams on foot, horseback, and ATVs combed over 47,000 hectares—an area larger than many cities. Divers probed nearby dams and water tanks, cadaver dogs sniffed for scents, and experts in outback survival analyzed every footprint and disturbance in the dust. For 10 grueling days, the effort persisted under blistering days and freezing nights, with locals in Yunta transforming their pub into a command center for care packages and morale boosts. Social media hashtags like #FindGus amassed millions of views, and national broadcasters provided round-the-clock coverage, turning the boy’s smiling face into a symbol of hope and horror.

Yet, no trace emerged. A single small footprint discovered 500 meters from the homestead initially sparked optimism, but forensics deemed it inconclusive—possibly from an animal or a prior visitor. Other leads, such as unusual vehicle sightings on the dusty Barrier Highway, fizzled under scrutiny. By October 4, SAPOL Deputy Commissioner Linda Williams delivered the gut-wrenching update: based on expert advice, survival odds in the harsh environment—where dehydration claims lives in hours and temperatures plummet at dusk—were “minimal.” The active search scaled back, transitioning to a recovery mode under the Major Crime Investigation Branch’s Missing Persons Unit. “We will never abandon hope,” Williams assured, but the shift marked a somber pivot from rescue to resolution.

Now, two weeks later, that hope flickers anew. On October 13, SAPOL announced the resumption of ground searches, set to begin today, October 14, in an expanded area of Oak Park Station beyond the original 470-square-kilometer zone. Bolstered by ADF troops experienced in desert maneuvers and advanced technology like ground-penetrating radar, the operation aims to scour previously inaccessible Crown land and adjacent properties. “New information and a re-evaluation of the terrain have prompted this,” Williams stated in a press briefing, though details remain guarded. Insiders speculate that forensic reviews of soil samples and family interviews have yielded subtle clues, prompting a “for completeness” sweep westward toward Belalie North, where Gus’s father, Joshua Lamont, resides about 100 kilometers away.

It’s against this backdrop that Gary Jubelin’s theory emerges, a stark reminder that not all outback vanishings are mere mishaps. Jubelin, a veteran detective who spearheaded the search for missing toddler William Tyrrell in New South Wales—a case that gripped Australia with its own web of theories and frustrations—spoke candidly to news.com.au about Gus’s plight. Drawing parallels to Tyrrell’s 2014 disappearance from a rural foster home, Jubelin posited a multifaceted scenario: “Police would be looking at, did young Gus disappear through misadventure, wander off, or was there some form of intervention, either human intervention or even, given the nature of the land out there, perhaps wildlife.” His words carry the weight of experience; in the Tyrrell case, Jubelin pursued leads from abduction to accident, ultimately resigning amid controversy but never wavering in his belief that foul play lurked.

The “wildlife” angle is particularly chilling in South Australia’s outback, a region teeming with feral dogs, dingoes, and kangaroos capable of traversing vast distances. Jubelin elaborated: “When a young child of Gus’s age disappears, it’s a horrible thing, and it has so many ramifications for all the people that knew Gus and are related to Gus. So, I fully understand why the police are doing what they’re doing.” He stressed the need for exhaustive re-examination, echoing another former officer, Aaron Stuart, who told The Advertiser: “I honestly believe the answer is back there on the property. Go back, rethink it, re-interview everybody, but take them back not 30 minutes, take them back a week.” Stuart, with decades tracking fugitives in the bush, advocates rewinding the timeline to uncover overlooked details—perhaps a visitor, a vehicle, or a family dynamic that holds the key.

These theories inject a layer of dread into what many hoped was a simple wandering case. The outback’s perils are legion: dry creek beds that flood unpredictably, abandoned mine shafts camouflaged by spinifex, and temperatures swinging from 28°C (82°F) daytime highs to 10°C (50°F) lows. Gus, small at under a meter tall and 18 kilograms, was a “good walker” per family friends, but in this terrain, even short distances spell danger. Wildlife involvement evokes echoes of the Azaria Chamberlain case, where a dingo snatched a baby from a tent in 1980, leading to decades of legal turmoil. Human intervention, meanwhile, raises specters of abduction—though police deem it low-probability in such isolation—or accidental harm covered up in panic.

The Lamont family’s dynamics add complexity. Gus lived primarily at Oak Park with Jess and Ronnie, under Josie’s care—a transgender woman known locally as “tough as nails” for managing the station through hardships. Joshua, a former country musician performing as Billy Tea, lives separately in Belalie North due to reported tensions over the children’s safety. “Josh doesn’t think it’s safe out there,” a family friend confided anonymously. Lamont has been “furious” but cooperative, pushing for westward expansion. Jess, in a poignant statement via police, pleaded: “Our little boy is the light of our world. Please, help us find him.”

Community support remains fervent. In Yunta, a speck with a pub and fuel stop, residents organize volunteer drives and vigils. Fleur Tiver, a 66-year-old neighbor, expressed relief: “Expanding makes sense—this land hides secrets.” Nationally, parallels to cases like Daniel Morcombe or Cleo Smith—both resolved after years—fuel optimism. Yet, misinformation plagues: viral posts claim dingo attacks or family cover-ups, debunked by AAP fact-checkers as “cruel hoaxes.”

As teams assemble at dawn today, the mood blends resolve and realism. SAPOL vows forensic combing, with private resources from Lamont aiding. Jubelin’s theory, while unsettling, sharpens focus: “The answer is there,” Stuart insists. For a nation transfixed, Gus’s story embodies vulnerability in vastness. If you have information, call Crime Stoppers at 1800 333 000. In the outback’s endless horizons, one boy’s light must not fade.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2)/august-gus-lamont-100225-2-3c5079ae56b64bdca5f441f3180f6637.jpg)

The financial and emotional toll is immense, but the drive persists. Volunteers like Jason O’Connell, who logged 1,200 kilometers in the initial push, lace up boots again: “We told ourselves he’s out there. Now, we know we must look harder.” Indigenous trackers, with land knowledge spanning generations, lead the way, reading signs in the saltbush that tech misses.

Jubelin warns against complacency: “These cases turn on details—a shoe print, a whisper. Human or animal, intervention changes everything.” Wildlife experts note dingo packs roam the region, capable of dragging small prey miles. Human foul play? Police probe visitors to the station, though isolation makes strangers rare.

For the McCanns—wait, Lamonts—the wait is agony. Josie broke silence: “We’re devastated, but believing.” Joshua pledges: “I’ll search forever.” As stars pierce the outback sky, one question lingers: Where is Gus? In a land of secrets, today’s hunt may unlock it.

The resumption signals SAPOL’s commitment. With ADF’s desert expertise, drones resume flights, radar penetrates soil. “No stone unturned,” Williams promises. As Yunta’s pub buzzes with hope, Australia holds breath. Gus, with his Minions shirt and fearless spirit, deserves answers.

News

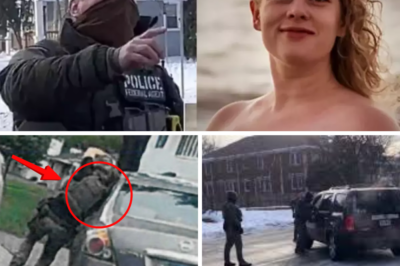

ICE Agent Involved in Fatal Shooting of Renee Good Previously Dragged 300 Feet by Vehicle in Bloomington Incident

Minneapolis, Minnesota – January 20, 2026 — The U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agent who fatally shot 37-year-old Renee…

Renee Good’s Family Refuses to Back Down: They’ve Quietly Retained One of America’s Top Attorneys — and Are Now Preparing to Release the Final Audio Recording That Could Change Everything

The family of Renee Nicole Good, the 37-year-old Minneapolis mother fatally shot by a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)…

Zion Foster Breaks Social Media Silence with Heartwarming Video of Daughter Story Amid Reports of Split from Jesy Nelson

London, January 20, 2026 — In his first public post since reports emerged of his separation from Jesy Nelson, musician…

Jesy Nelson Confirms Split from Fiancé Zion Foster Amid Heartbreaking Reality of Twins’ SMA Diagnosis

In a development that has left fans reeling, former Little Mix singer Jesy Nelson has confirmed the end of her…

A Teacher Everyone Trusted — Then She Vanished: The Tragic Case of Linda Brown and Lingering Questions After Her Lake Michigan Death

In the tight-knit Bridgeport community of Chicago, Linda Brown was more than just a special education teacher at Robert Healy…

Ex-Husband in Ohio Dentist Murders Allegedly Used Fake Details to ‘Disguise’ Himself Before Killings, Expert Says

Columbus, Ohio – January 20, 2026 — New revelations in the high-profile double murder case involving an Ohio dentist and…

End of content

No more pages to load