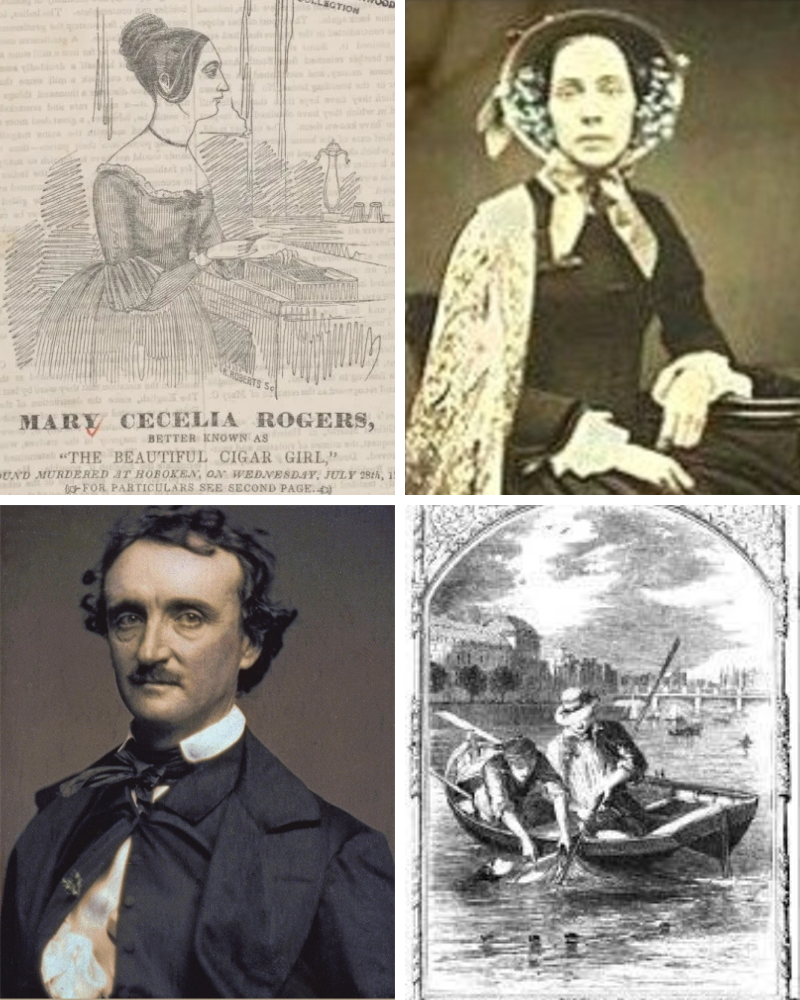

In the sweltering summer heat of July 1841, Manhattan buzzed with a scandal that gripped the penny press and parlor conversations alike: The brutal murder of Mary Cecilia Rogers, a 20-year-old tobacco shop clerk dubbed “The Beautiful Cigar Girl” for her striking looks and flirtatious charm. Her body, discovered floating in the Hudson River off Hoboken, New Jersey, on July 28—bruised, strangled, and clad in a torn dress—ignited a media frenzy, unsolved theories, and a nation’s fascination with violent mystery. Edgar Allan Poe, then a struggling writer in Philadelphia, devoured every headline, transmuting the tragedy into “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt” (1842-43), a novella that pioneered deductive reasoning in fiction, analyzing real clues amid a Parisian veil. Yet Poe’s own life ended in baffling obscurity eight years later, on October 7, 1849, transforming the architect of mysteries into one himself—a delirious figure in borrowed clothes, incoherent on Baltimore streets, his death at 40 shrouded in speculation that endures nearly two centuries on.

Mary Rogers’ story was tabloid gold in an era when “true crime” was nascent sensationalism. Born in 1820 in Lyme, Connecticut, to a widowed mother, Mary moved to New York at 16, working at her cousin’s cigar store on Broadway. Her beauty—raven hair, porcelain skin, and a smile that drew poets and politicians—made her a celebrity; Nathaniel Hawthorne allegedly modeled her in tales, while suitors like cork cutter Daniel Payne and boardinghouse lodger Alfred Crommelin vied for her hand. On July 25, 1841, Mary vanished after telling her fiancé Payne she was visiting aunt in the countryside. Three days later, Hoboken beachcombers spotted her corpse: Garroted with a corset stay, dress ripped (suggesting assault), body weighted but buoyed by tides. The New York Herald screamed “MYSTERIOUS MURDER!”—sales soared, theories proliferated: Gang rape by ruffians? Botched abortion (rumors of a secret pregnancy)? Suicide pact gone wrong?

Investigations floundered. Coroner Richard Cook ruled homicide by strangulation and drowning; evidence included a sailor’s knot on her petticoat, hinting at waterfront thugs. Payne, despondent, overdosed on laudanum at the scene weeks later. A “deathbed confession” from Hoboken innkeeper Frederica Loss—claiming Mary died from a botched procedure at her roadhouse, body dumped by accomplices—emerged in October, but Loss recanted amid bribes suspicions. No arrests stuck; the case fizzled, emblematic of 1840s policing woes—corrupt constables, no forensics, class biases shielding elites.

Poe, obsessed, relocated the drama to Paris in “Marie Rogêt,” serializing it in Snowden’s Ladies’ Companion (November 1842-February 1843). His detective C. Auguste Dupin—debuted in “Murders in the Rue Morgue” (1841), genre’s genesis—dissects newspaper clippings, debunking suicide (tides would bloat differently), favoring gang assault over abortion (no medical evidence). Poe predicted a “naval officer” lover and dark-skinned assailant, eerily aligning with later whispers of Mary’s beau, a ship captain. He revised post-Loss confession, endorsing the abortion theory—proving fiction’s fluidity with fact. Critics hailed it as “ratiocination’s triumph”; sales boosted Poe’s fame, influencing Conan Doyle’s Sherlock (who nods Dupin). Yet accuracy faltered: Poe ignored cultural contexts, like New York’s seedy cigar culture fostering harassment.

Poe’s own end mirrored his tales’ ambiguity. By 1849, broke and bereaved (wife Virginia died 1847), he lectured in Richmond, courting widow Sarah Royster. On September 27, he boarded a Baltimore train; next seen October 3, delirious outside Gunner’s Hall tavern, in ill-fitting clothes (not his), muttering “Reynolds!”—a code? Election judge? Delusion? Dr. John Moran admitted him to Washington College Hospital; Poe raved of “darkness” and “wife,” dying four days later. Official cause: “congestion of the brain” (euphemism for alcohol poisoning). Theories abound: Cooping (election gangs drugging voters, forcing polls in disguises—1849 was voting day)? Rabies (hallucinations match)? Murder by Royster’s brothers? Poisoned by political foes? His medical notes vanished; autopsy denied. Biographer Rufus Griswold’s smears (calling him mad drunk) muddied waters.

In 2025, forensics retry: A 1990s study suggested rabies (no bite scars, but hydrophobia fits); DNA on letters hints epilepsy. Podcasts like “Unresolved” dissect cooping—Poe’s anti-Whig stance made enemies. Mary’s case, too, revives via “The Beautiful Cigar Girl” (2006 book by Daniel Stashower), positing abortion by Dr. Cook’s kin. Both enigmas fuel genre: True crime’s boom (podcasts hit 1 billion downloads 2024) owes Poe, whose Dupin birthed CSI logic.

Mary (1820-1841) and Poe (1809-1849): Victims of era’s shadows—violence unchecked, deaths unexplained. Poe’s quoth: “The death of a beautiful woman is unquestionably the most poetical topic.” His legacy? Eternal riddle, where fact blurs fiction, leaving us breathless in pursuit.

News

Rihanna Responds to a Fan Saying, “They Saying It’s 2016, Rih”: What Her Viral Reply Really Means

When a fan recently commented, “They saying it’s 2016, Rih,” few expected Rihanna to respond. She often ignores random online…

Rihanna’s Unmatched Face Card: How One Look Became a Cultural Phenomenon

Few celebrities command attention the way Rihanna does. Across red carpets, candid street photographs, and unfiltered social media moments, one…

400,000 FRANCS FOR RELEASE: PROSECUTORS SEEK BAIL FOR OWNERS AFTER DEADLY CRANS-MONTANA NEW YEAR FIRE

Prosecutors in Sion have requested a total of 400,000 Swiss francs in bail to grant provisional freedom to Jacques and…

📰 RCMP RELEASES NEW TIMELINE DETAILS IN LILLY AND JACK SULLIVAN CASE AS ALLEGED MESSAGES SPARK FRESH CLAIMS

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has entered another sensitive phase as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police released new…

JUST NOW: Investigators Flag Timeline Issues and Re-Examine Key Details in the Disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has taken an unexpected and unsettling turn, according to the latest update released…

A new wave of controversy erupted online this week after the daughter of an NBA legend reportedly came forward with what she described as troubling information involving Stefon Diggs and his relationship with Cardi B.

According to circulating social-media claims, she suggested that Cardi B should reconsider her involvement with the NFL star, citing alleged…

End of content

No more pages to load