THE VANISHING OF GUS LAMONT: Cracks in the Family Facade as Police Probe Deeper into Outback Mystery

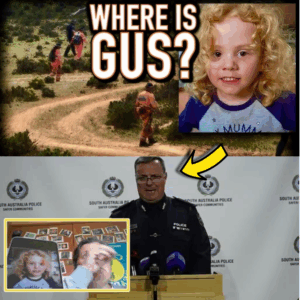

In the relentless red dust of South Australia’s Flinders Ranges fringe, where the outback’s vast emptiness can swallow a soul whole, four-year-old Augustus “Gus” Lamont’s playful afternoon turned into a national nightmare on September 27, 2025. Around 5 p.m., under a sky streaked with the day’s fading light, Gus was spotted by his grandmother Shannon Murray frolicking on a simple mound of dirt just outside the family’s isolated Oak Park Station homestead—43 kilometers south of the tiny outpost of Yunta, some 300 kilometers north of Adelaide. Clad in a blue long-sleeved Minions shirt from Despicable Me, light grey pants, boots, and a grey broad-brimmed hat, the shy yet adventurous toddler embodied the innocent joy of rural life. But by 5:30 p.m., when Shannon stepped out to call him in for dinner, the yard was eerily empty. Gus had vanished in that razor-thin 30-minute window, igniting one of the most baffling missing child cases in Australian history. Twelve days later, on October 9, the official story from his fractured family is fraying at the seams, with police quietly expanding their lens beyond the scrubland to the homestead’s own shadowed corners.

Oak Park Station sprawls across 60,000 hectares of flat, unforgiving gibber plains and spinifex grass, a sheep property where isolation is both livelihood and curse. The modest homestead, a weatherboard relic amid endless horizon, housed Gus’s mother Jess Lamont, his one-year-old brother Ronnie, and his grandparents Shannon and Josie Murray. Josie, a transgender woman who transitioned years ago, shared a deep bond with the boys, helping raise them in this remote haven. But harmony was illusory. Gus’s father, Joshua Lamont, lived 100 kilometers away in Belalie North near Jamestown—a two-hour drive over dusty tracks—estranged from the daily scene due to explosive clashes with Josie. Locals whisper of heated arguments over the property’s dangers: roaming dingoes, flash floods in dry creek beds, and the sheer remoteness that Joshua deemed unfit for young children. Though Jess and Joshua remain a couple, the tensions simmered, with Joshua absent that Saturday, only learning of the disappearance hours later when police roused him from sleep. No frantic family call—just official notification after the sun had set and searches had begun.

The family’s narrative unfolds like a script from a rural drama: momentary distraction inside the house, Gus wanders off, they scour the property for three full hours—sheds, mounds, gullies—before dialing triple zero around 8:30 p.m. Darkness had descended by then, the mercury dropping from 28 degrees Celsius daytime heat to a frigid 10 degrees at night. Rescue mobilized at warp speed: South Australian Police’s Polair helicopter with infrared scanners thumped overhead, State Emergency Services volunteers (up to 30 daily), Aboriginal trackers attuned to the land’s whispers, trailbikes ripping across 1,200 kilometers of terrain, all-terrain vehicles, and even 48 to 50 Australian Defence Force personnel for intensive sweeps. Drones, including a cutting-edge infrared model borrowed from high-profile murder probes, mapped the vastness, while divers probed nearby dams and waterholes. It was, by Assistant Commissioner Ian Parrott’s account, one of SA Police’s largest, most grueling operations ever.

Hope flickered briefly with clues that evaporated like morning dew. A single child-sized footprint, etched 500 meters from the homestead, hinted at a path toward a fence line—but trackers like Aaron Stuart dismissed it as anomalous, noting isolated prints don’t materialize alone; where one treads, a trail follows. Another small boot print near a dam, 5.5 kilometers west, spurred a frantic targeted search on October 6, but forensics ruled it unrelated too. No hat snagged on spinifex, no clothing fibers in the dirt, no echoes of a crying child on the wind-swept plains. Not even wedge-tailed eagles, those opportunistic outback sentinels, betrayed unusual scavenging. SES veteran Jason O’Connell, who logged 90 hours with his partner alongside Joshua—described as “devastated” beyond words—proclaimed the bafflement: “A four-year-old doesn’t disappear into thin air; he has to be somewhere.” Yet after 10 days, on October 7, Parrott announced the scale-back to recovery mode. Medical experts, citing survival timelines for a preschooler sans food, water, or shelter in extreme conditions, pegged odds at near zero. The Missing Persons Investigation Section under the Major Crime Branch took over, with drone data still under analysis—results potentially weeks away.

That 30-minute enigma gnaws at the core. On open, flat terrain where sounds carry kilometers, how does a four-year-old—good walker or not, but never before straying from home—evaporate without a cry piercing the dusk? By 6:30 p.m., twilight yields to pitch black; tired legs falter, hunger bites, fear roots a child in place. Statistics scream: 90% of missing under-fives surface within the hour, often nearby, found by kin. Gus’s case mocks this—three hours of family-led probing before external aid, despite satellite phones standard on such stations. Why the delay? And Joshua’s late alert fuels whispers: was it oversight in chaos, or something calculated amid feuds? Family friend Fleur Tiver hails the Murrays as “kind, gentle, reliable, truthful,” slamming online trolls peddling foul play. Neighbor Alex Thomas decries “vitriol” accusing the “gentle and loving” clan, begging compassion for rural realities. Yet former homicide detective Gary Jubelin, scarred by the William Tyrrell saga, reads police phrasing—”concurrent inquiries to rule out every option,” “further lines of enquiry”—as code for probing intervention, not just misadventure.

Police tread carefully: Parrott lambasts “keyboard detectives” for tormenting the “clearly distraught” family, who’ve greenlit every request. Acting Commissioner Linda Williams affirms full cooperation, vowing no surrender. But actions diverge from words. The pivot to Major Crime signals scrutiny: phone logs, vehicle tracks from the battered Land Rovers, homestead forensics for digital breadcrumbs or overlooked nooks. Josie Murray, breaking silence, insists, “We’re still looking for him,” rebuffing volunteers at the gate for privacy. In Yunta’s tight 100-soul community, Josie’s identity stirs conservative murmurs, amplifying speculation in custody-tinged shadows. Was a boiling argument—over safety, access, the boys’ future—the spark in that half-hour void? Online forums erupt: dingo snatch? Hidden crevice? Or human hand, veiled by grief’s curtain?

Twelve days etch eternity. Gus’s first photo, released six days post-vanishing—tousled blond hair, gap-toothed grin—plasters hearts nationwide. The outback devours: explorers, stockmen, the unwary. But Gus, knee-high and bookish, defies wilderness lore. Searcher O’Connell’s gut: “He’s not on that property”—no fox howls, no raptor dives signaling remains. If not the land’s maw, then where? Police’s infrared redux or forensic deep-dive may unearth truths, but the family’s unified front—Jess’s silence, Josie’s resolve, Shannon’s last glimpse—cracks under timeline’s weight. Tensions with Joshua, unspoken in officialdom, loom like thunderheads.

For Gus, the cherub lost in 30 impossible minutes, Australia’s pulse quickens. The homestead’s quietude, once alive with toddler glee, now harbors questions. As investigators peel isolation’s layers, one certainty endures: in misadventure’s void, doubt festers. The outback’s silence demands answers—from the wild, or worse, from within. Little Gus waits; time erodes hope, but truth must emerge.

News

William Reveals Lady Louise’s Hidden Estate Inheritance – Camilla’s Fury Erupts Over Queen’s Final Snub.

Prince William has reportedly broken decades of royal silence by disclosing previously undisclosed details about a private inheritance bestowed upon…

“Be Kind”: Melanie Sykes’ Raw Confession of Severe Hair Loss & Constant Pain Leaves Fans Devastated.

Melanie Sykes, the beloved British television presenter and model once known for her radiant confidence and infectious energy on shows…

Two Weeks of Silent Stalking Ended in Targeted Execution: Tipp City Police Confirm Grisly Ambush on Ex-Teacher.

Tipp City Police have officially labeled the early-morning shooting death of 37-year-old Ashley Flynn a premeditated, targeted assassination after uncovering…

Suicide Note’s Heartbreaking Confession: Why a Utah Mom Killed Her Cheerleader Daughter in Vegas Hotel.

The discovery of a handwritten suicide note has cast a somber light on the murder-suicide that claimed the lives of…

Virginia Giuffre’s Family: “Broken Hearts Lifted” After Andrew’s Arrest – “He Was Never a Prince”.

The family of the late Virginia Roberts Giuffre released a poignant statement Thursday expressing profound relief and gratitude following the…

King Charles Vows ‘Full Support’ for Andrew Probe: ‘Law Must Take Its Course’ After Birthday Arrest.

King Charles III has publicly pledged the royal family’s “full and wholehearted support and co-operation” to authorities investigating his younger…

End of content

No more pages to load