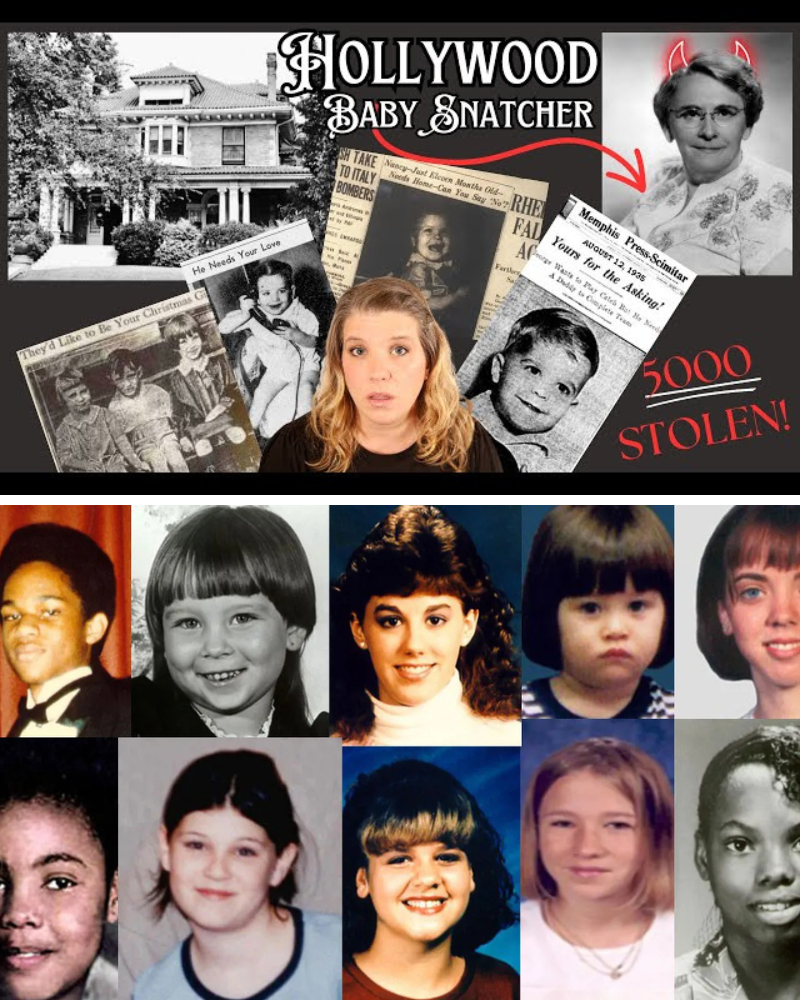

For over two decades, from the Roaring Twenties through the post-World War II boom, a shadowy figure haunted the doorsteps of desperate single mothers across Tennessee, Arkansas, and Mississippi. Posing as a benevolent social worker, she dangled promises of aid—medical care, financial relief, a brighter future for their newborns—only to vanish with the infants in tow, leaving behind fabricated tales of tragedy. “Your baby didn’t make it,” she’d claim, or “We’ve found a loving home; sign here for the best.” But the truth, unearthed in a bombshell 1950 investigation, was far grimmer: Beulah George “Georgia” Tann, director of the Tennessee Children’s Home Society’s Memphis branch, orchestrated the largest child-trafficking ring in U.S. history, abducting and selling at least 5,000 children to wealthy families nationwide for fees up to $10,000 (over $130,000 today). Operating from a grand Victorian mansion at 1556 Poplar Avenue—a once-stately home that masked unimaginable horrors—Tann’s empire preyed on the vulnerable, falsified records, and buried secrets that would take generations to exhume. The scandal, exposed just before her death, prompted sweeping adoption reforms but left a trail of fractured families, lost identities, and untold grief that echoes to this day.

Tann’s operation, which flourished from 1924 until her demise in 1950, was a masterclass in deception and exploitation. Born in 1891 to a prominent Mississippi judge, the ambitious but unqualified Tann (who failed her teaching certification) arrived in Memphis in 1922, leveraging family connections to snag the executive director role at the Tennessee Children’s Home Society—a legitimate orphanage chain with branches in Knoxville, Chattanooga, and Jackson. Under her watch, the Shelby County branch ballooned into a profit machine, but not through charity. Tann targeted poor, unwed mothers—often in hospitals, jails, or shantytowns—convincing them their babies were “better off” elsewhere. Nurses on her payroll flagged “desirable” infants (blond, blue-eyed, healthy), while deputies and doctors fabricated abandonment claims or death certificates. One mother, Alma Jo Davis, handed over her newborn Billy Joe Woodbury in 1945 for “temporary care,” only to be told he perished; decades later, she learned he’d been sold to a California couple. Another, Mary— a fictionalized composite from survivor accounts—arrived at the mansion with bread in hand to retrieve her child, only to face blank stares from staff: “No record of any such baby.”

The Poplar Avenue mansion, with its terra-cotta roof and pillared porch, served as both facade and fortress. To outsiders, it was a beacon of benevolence; inside, it was a “house of horrors.” Children endured squalid conditions: Overcrowded dorms with minimal sanitation, inadequate food leading to malnutrition, and rampant illness in unventilated rooms. At least 500 died under Tann’s care—official tallies cite pneumonia and dysentery, but whistleblowers alleged neglect and experimental “treatments” to “toughen” them for sale. Survivor Deveraux “Devy” Eyler, abducted at birth in 1937, recalled in her 2010 memoir being shuttled in unmarked vans, dosed with sedatives, and paraded like merchandise at “adoption parties” for elite buyers. Tann curated elaborate backstories—claiming babies were “orphans of the wealthy” fallen on hard times—to fetch premium prices, pocketing 80-90% of fees while funneling scraps to the society. Her network extended coast-to-coast: Among unwitting buyers were celebrities like Joan Crawford (whose adopted twins were later revealed as Tann victims) and June Carter Cash.

Tann’s impunity stemmed from ironclad protection. She cultivated ties with Memphis power brokers: Juvenile Court Judge Camille Kelley rubber-stamped custody orders (often without hearings), while political boss E.H. “Boss” Crump—mayor for decades—shielded her from scrutiny. Eugenics ideology fueled the fire; Tann, a self-proclaimed “expert” on child placement, targeted “undesirables” (poor whites, immigrants) to “improve” the gene pool for affluent adopters. When rumors surfaced—via 1930s complaints from birth mothers or a 1937 state report flagging irregularities—investigations fizzled. Tann even lobbied for sealed adoption records, a law passed in 1951 that buried evidence deeper.

The empire crumbled in 1950, mere months before Tann’s death from cancer on September 15. Governor Gordon Browning, facing reelection pressure and tipped off by a Kansas probe into a stolen child, dispatched investigator Robert Taylor to Memphis. Taylor’s report—detailing falsified documents, missing funds ($1 million skimmed), and child graves—ignited a firestorm. The society shuttered, Kelley escaped charges (dying in 1955), and Crump’s machine crumbled. Reforms followed: Tennessee’s 1951 adoption laws mandated oversight, background checks, and open records (partially; full access came in 2020). Nationally, Tann’s model influenced ethical standards, but scars lingered—victims like NASCAR driver Gene Tapia, whose son was snatched during his WWII service, or wrestler Ric Flair, trafficked as an infant.

Decades on, the fallout festers. Sealed files thwarted reunions until “Unsolved Mysteries” (1989 episode) and “60 Minutes” (1991) sparked a deluge of tips to Tennessee’s Right to Know, a volunteer group reuniting families. Alma Sipple, duped in 1945, reunited with daughter Irma (now Sandra) after 44 years via the show. Books like Lisa Wingate’s “Before We Were Yours” (2017)—a fictionalized account topping bestseller lists—and “The Baby Thief” (2007) by Barbara Raymond revived awareness, leading to 2018-2019 survivor reunions in Memphis where adoptees like Norma Sue’s daughters scattered ashes along the Mississippi. Yet pain persists: Adoptees battle identity crises, birth mothers grapple with fabricated grief. A 2023 Hastings Women’s Law Journal piece calls for reparations—a victim fund from state coffers—to address “unquantifiable losses.”

Today, the Poplar mansion—now a parking lot for an apartment complex—stands as a ghostly relic, marked by a discreet plaque from the Tennessee Historical Commission. The society’s name lives on innocently in a modern Nashville orphanage, but Tann’s shadow looms in debates over sealed records and adoption ethics. As one survivor, Virginia Williamson, told Business Insider in 2019: “She played God with our lives.” In 2025, with DNA testing unraveling more secrets (a 2024 Genealogy for Justice project identified 200+ Tann victims), closure inches closer—but for thousands, the mansion’s dark whispers endure, a speechless testament to unchecked power and unbreakable human bonds.

News

Rihanna Responds to a Fan Saying, “They Saying It’s 2016, Rih”: What Her Viral Reply Really Means

When a fan recently commented, “They saying it’s 2016, Rih,” few expected Rihanna to respond. She often ignores random online…

Rihanna’s Unmatched Face Card: How One Look Became a Cultural Phenomenon

Few celebrities command attention the way Rihanna does. Across red carpets, candid street photographs, and unfiltered social media moments, one…

400,000 FRANCS FOR RELEASE: PROSECUTORS SEEK BAIL FOR OWNERS AFTER DEADLY CRANS-MONTANA NEW YEAR FIRE

Prosecutors in Sion have requested a total of 400,000 Swiss francs in bail to grant provisional freedom to Jacques and…

📰 RCMP RELEASES NEW TIMELINE DETAILS IN LILLY AND JACK SULLIVAN CASE AS ALLEGED MESSAGES SPARK FRESH CLAIMS

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has entered another sensitive phase as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police released new…

JUST NOW: Investigators Flag Timeline Issues and Re-Examine Key Details in the Disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has taken an unexpected and unsettling turn, according to the latest update released…

A new wave of controversy erupted online this week after the daughter of an NBA legend reportedly came forward with what she described as troubling information involving Stefon Diggs and his relationship with Cardi B.

According to circulating social-media claims, she suggested that Cardi B should reconsider her involvement with the NFL star, citing alleged…

End of content

No more pages to load