In the scorched, labyrinthine badlands of southern Utah, where the desert sun etches ancient secrets into red rock canyons and forgotten relics of America’s atomic age rust in silence, a discovery in August 2019 shattered a decade of silence. Deep within the sealed shafts of an abandoned uranium mine near Temple Mountain, a group of geology students stumbled upon a scene straight out of a nightmare: two skeletons, fully clothed and seated side by side on rusted folding chairs, as if frozen in eternal conversation. The remains belonged to Sarah Bennett, 26, and Andrew Miller, 28—adventurous sweethearts from Colorado who had vanished without a trace during a weekend getaway in May 2011. Their bodies, preserved in the mine’s dry, toxic embrace, offered a chilling epilogue to one of the American Southwest’s most baffling missing persons cases. For nearly eight years, families agonized, investigators chased shadows, and conspiracy theories festered like open wounds. Now, with the truth unearthed from the earth’s unforgiving vault, the story of Sarah and Andrew stands as a stark reminder of how the wilderness can claim lives with indifferent cruelty, leaving only echoes in the dust.

Sarah Bennett and Andrew Miller were the epitome of young love in bloom—a couple whose shared passion for the outdoors painted their lives in vibrant strokes of adventure and spontaneity. Sarah, a vivacious graphic designer from Denver with a cascade of auburn curls and a laugh that could light up the dimmest room, had grown up hiking the trails of Rocky Mountain National Park, her camera always slung over her shoulder to capture fleeting sunsets and wildflower meadows. At 26, she was the free spirit in her circle of friends, the one who dragged everyone on impromptu road trips, her Instagram feed a mosaic of cliffside yoga poses and starry-night campfires. Andrew, 28, was her perfect counterbalance: a software engineer with a lanky frame, wire-rimmed glasses, and a quiet intensity that masked a deep well of curiosity. Hailing from Boulder, he traded coding marathons for weekend escapes into nature, where he found solace sketching geological formations or debating the ethics of off-grid living. They met two years earlier at a sustainability conference in Fort Collins, bonding over vegan tacos and a mutual disdain for urban sprawl. “They were soulmates,” Sarah’s older sister, Emily Bennett, would later recall in a tearful interview. “Always planning the next horizon, hand in hand.”

By the spring of 2011, Sarah and Andrew had been living together in a cozy loft apartment overlooking Denver’s Platte River, their walls adorned with framed prints of Zion’s slot canyons and Arches’ delicate arches. Work had been grinding—endless deadlines for Sarah’s freelance gigs, buggy code for Andrew’s startup—but they craved renewal. “We need to unplug, just us and the stars,” Sarah texted a friend on May 13, attaching a photo of their packed Subaru Outback, its roof rack groaning under tents and coolers. Their destination: the San Rafael Swell, a 75-mile-long anticline of warped sandstone in Emery County, Utah, often called the “Utah Grand Canyon” for its otherworldly hoodoos, petrified dunes, and labyrinth of slot canyons. This remote expanse, pockmarked by relics of the 1950s uranium boom that fueled America’s Cold War arsenal, promised solitude and surreal beauty. It was a three-day jaunt: drive from Denver on Friday, camp under the Milky Way, hike hidden trails, and return by Sunday evening. They stocked up on energy bars, a paper map of the area (GPS signals were notoriously spotty), and Sarah’s trusty Nikon D3100 for those “magic hour” shots. Friends waved them off with hugs and jokes about not getting lost in the “moonscape.”

The last traces of the couple surfaced at a dusty gas station in Green River, Utah, around 4 p.m. on Friday, May 20. Surveillance footage, grainy but poignant, captured them in high spirits: Andrew pumping gas into the Subaru, Sarah leaning against the hood in cutoff shorts and a faded Patagonia tank, both breaking into laughter over some shared quip. She grabbed a stack of trail mix and that Emery County map from the convenience store, paying with a flourish of cash. “Adventure awaits!” she scrawled in a quick note to Emily, snapping a selfie with the pump in the background. Then, nothing. No check-ins, no texts, no posts. By Monday morning, when they missed work and ignored frantic calls, alarm bells rang. Emily filed a missing persons report with Denver PD, who looped in Utah authorities. “They wouldn’t just ghost us,” Andrew’s brother, Michael Miller, insisted, his voice cracking over the phone. What followed was a frenzy of desperation: family road trips scouring canyon rims, pleas on milk cartons and Craigslist, even a psychic who claimed visions of “glowing rocks.”

The search effort ballooned into a multi-agency spectacle, one of the largest in Utah’s recent history. Emery County Sheriff’s deputies, bolstered by Colorado Search and Rescue volunteers, deployed helicopters with thermal imaging, bloodhounds sniffing faded scents, and ground teams hacking through tamarisk thickets. Drones buzzed over the Swell’s 2,000 square miles of badlands, while fixed-wing planes circled from dawn to dusk. The terrain was a searcher’s nightmare—twisting slot canyons no wider than a shoulder, sheer drops into forgotten mineshafts, and flash-flood scars that could swallow a vehicle whole. Uranium mining scars added peril: open adits laced with radon gas, unstable tailings piles that could avalanche at a touch. “It’s like the land eats people,” a grizzled ranger told reporters, shaking his head at the operation’s base camp near Castle Dale. Over 200 volunteers combed the area for weeks, erecting billboards along I-70 with Sarah and Andrew’s faces—her impish grin, his thoughtful gaze—pleading for tips. Crime Stoppers lines lit up with leads: a sighting at a Moab diner (false), a wrecked Subaru in a wash (abandoned junker), whispers of cartel foul play near the border (baseless hysteria). But the desert yielded zilch. By July, the active phase wound down, morphing into a cold case file gathering dust in a Moab substation.

Years blurred into a limbo of quiet torment for those left behind. Emily Bennett channeled her grief into advocacy, founding the “Echoes in the Swell” foundation to fund GPS trackers for hikers and awareness campaigns on mine hazards. “Every spring, I drive out there, screaming their names into the wind,” she confessed in a 2015 podcast, her voice hollow. Michael Miller, once a rising architect, spiraled into isolation, quitting his firm to freelance from a cabin in the Rockies, haunted by voicemails of Andrew’s easy baritone debating craft beers. Conspiracy mills churned online: UFO abductions in the Swell’s “energy vortex,” organ-harvesting rings preying on tourists, even a government cover-up tied to Cold War uranium secrets. Tabloids feasted, dubbing it “The Uranium Lovers’ Curse.” Families held annual memorials at a pullout overlooking the Swell, releasing lanterns that danced like fireflies against the dusk, whispering prayers for closure. “We just want to bring them home,” Emily pleaded at a 2017 vigil, clutching a faded photo of the couple at their engagement dinner—Sarah’s ring glinting under string lights.

The breakthrough came not from high-tech wizardry or dogged detectives, but from wide-eyed academia. In August 2019, a dozen geology undergrads from the University of Utah’s Henry E. Huntington Department embarked on a field expedition to Temple Mountain, a uranium hotspot where ore veins once glittered like fool’s gold during the 1950s boom. Led by Professor Elena Vasquez, a specialist in paleogeology, the group was mapping seismic risks in legacy mines—shafts sealed post-1970s regulations but riddled with illegal entries by thrill-seekers and scavengers. Armed with hard hats, Geiger counters, and ropes, they rappelled into the Vanadium Queen Mine, a 300-foot-deep adit bored in 1953, its entrance barred by a chain-link fence tagged with faded warnings: “DANGER: NO TRESPASSING. RADIATION HAZARD.” Curiosity drew them deeper; one student, 21-year-old Jamal Ruiz, spotted a glint amid the rubble—a shattered lantern half-buried in tailings.

What they uncovered next froze the team in collective horror. Illuminated by headlamps, two skeletal figures sat slumped on corroded camp chairs, facing each other across a makeshift table of dynamite crates. Male and female, clad in desiccated hiking gear—her in a teal windbreaker, him in cargo pants and a flannel shirt—the bones articulated in seated repose, as if mid-chat over trail mix. Beside them: a Nikon camera with exposed film rolls intact, a thermos etched with “S&A Forever,” and a crumpled map marked with penciled routes to “Secret Arch.” The mine’s rear had collapsed in a rockfall, forming a airtight seal that mummified the scene, shielding it from scavengers and weather. “It was like walking into a tomb,” Professor Vasquez recounted later, her voice steady but eyes distant. “They looked… peaceful. Like they’d chosen to stay.” Geiger readings spiked—elevated radon—but no acute poisoning. The students radioed out, and within hours, FBI forensics swarmed the site, rappelling down with body bags and evidence kits.

Identification was swift and soul-crushing. Dental records matched Sarah’s orthodontics and Andrew’s wisdom tooth extraction; mitochondrial DNA from femur samples sealed it. The Nikon yielded haunting images: selfies at sunset over the Swell, shadowy mine interiors lit by flashlight, a final shot of the couple arm-in-arm at the entrance, captioned “Into the unknown—love you more.” Autopsies pegged time of death to late May 2011, cause “undetermined” but likely a cascade: disorientation in the maze-like mine, a slip into darkness, injuries from falling debris, compounded by dehydration and hypothermia in the unventilated shaft. No foul play—radon exposure chronic but not lethal, no trauma beyond fractures from the collapse. “They went exploring, got turned around, and the mountain took them,” the coroner summarized grimly. How they entered remains a riddle; the fence was intact, suggesting a side breach or curiosity overriding caution.

News of the find ripped through the nation like a haboob, dominating cable cycles and true-crime pods. Families converged on Moab for a somber repatriation, Emily clutching Sarah’s camera like a talisman, Michael staring at the map as if it held absolution. “Eight years of hell, and now this,” Emily told reporters, tears carving tracks in the dust on her cheeks. “They were right there, all along—holding hands, even in death.” Funerals followed: a joint service in Denver under a big-top tent, with eulogies blending grief and gratitude. Sarah’s ashes scattered in the Rockies she adored; Andrew’s interred beside his grandparents in Boulder, a plaque reading “Explorer Eternal.” The mine was dynamited shut, its scar a federal monument etched with their names.

The legacy endures in ripples. Emily’s foundation ballooned, partnering with the Bureau of Land Management for “Lost in the Swell” apps—GPS beacons and mine maps for adventurers. Utah upped patrols in mining districts, installing seismic sensors and warning kiosks at trailheads. True-crime enthusiasts dissected the case on Reddit’s r/UnresolvedMysteries, spinning yarns of “ghost miners” guiding the couple deeper. For locals, it’s folklore now—the “Chair of Lovers,” a cautionary whisper around Green River campfires. In a world of instant connectivity, Sarah and Andrew’s story underscores the wild’s whisper: beauty beckons, but boundaries bite. Eight years trapped in silence, they emerged not as victims, but as spectral sentinels—reminders that some horizons, once crossed, close forever. In the Swell’s eternal hush, their chairs sit empty, waiting for the next wanderers to heed the warning carved in stone: Enter at your peril.

News

The Maid Who Fought Back: Sophia Ramirez’s Unjust Firing and the Billionaire’s Life-Changing Gesture

In the shadow of Seattle’s gleaming skyscrapers, where the tech titans of the Pacific Northwest weave fortunes from lines of…

From Deathbed Betrayal to Triumphant Return: Emily Hargrove’s Miraculous Survival and Calculated Revenge

In the sterile corridors of Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital, where the hum of ventilators and the scent of antiseptic blend…

Chaos Behind the Curtain: Meghan Markle’s ‘Royal Diva’ Demands at Balenciaga’s Paris Show Leave Anne Hathaway Stunned

In the opulent haze of Paris Fashion Week, where the air crackles with the scent of Chanel No. 5 and…

Duchess to influencer: Meghan Markle reveals plans to release ‘short social media films’ after Netflix ended $100m deal

In the sun-kissed enclaves of Montecito, where eucalyptus groves whisper secrets to the Pacific breeze and the Sussexes’ $14.7 million…

Meghan Markle Shares Heartfelt Photos and Videos of Princess Lilibet on International Day of the Girl

In the sun-dappled serenity of Montecito’s sprawling estates, where bougainvillea vines climb sun-warmed walls and the Pacific breeze carries whispers…

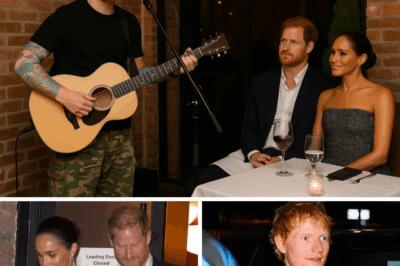

Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s Intimate Soho House Dinner with Ed Sheeran in New York

In the heart of Manhattan’s vibrant Meatpacking District, where the Hudson River’s gentle lapping meets the hum of high-society whispers,…

End of content

No more pages to load