YUNTA, South Australia – In the vast, unforgiving expanse of the Australian outback, where red dust stretches endlessly under a merciless sun, a family’s worst nightmare has unfolded into a nation’s collective heartbreak. Six days ago, on the crisp morning of September 29, 2025, four-year-old August “Gus” Lamont vanished without a trace from his grandparents’ remote sheep station, some 30 kilometers south of the dusty town of Yunta in South Australia’s mid-north. What began as a routine day of play amid the shearing sheds and weathered homestead has spiraled into one of the most harrowing missing persons cases in recent memory, leaving behind just one chilling remnant: a solitary child-sized footprint etched into the parched earth, approximately 500 meters from the family home.

As of October 5, the search for little Gus – a cherubic-faced boy with tousled blond hair, bright blue eyes, and an infectious giggle that echoed through the isolated property – presses on with renewed desperation. Police have scaled back the massive operation that mobilized hundreds of volunteers, helicopters, drones, and cadaver dogs, but they returned to the scene yesterday in a bid to chase down fresh leads. “Our hearts are aching,” said Assistant Commissioner Grant Stevens during a somber press conference on October 4. “We’re not giving up on Gus. Every possibility is being explored, but time is not on our side in this environment.”

The outback, often romanticized in Australian lore as a land of rugged adventure, reveals its brutal side in stories like this. Temperatures here soar past 30 degrees Celsius even in early autumn, and the terrain – a labyrinth of saltbush scrub, dry creek beds, and rocky gullies – swallows secrets whole. Gus’s disappearance has gripped the nation, evoking memories of past tragedies like the 2019 loss of three-year-old Egyptian boy Anthony Mifsud in nearby bushland. But Gus’s case carries an extra layer of torment: that lone footprint, discovered on the third day of the search by a sharp-eyed ground team combing the paddocks. It measured roughly the size of a four-year-old’s shoe, pressed lightly into the cracked soil as if the child had paused, perhaps looking back, before stepping into oblivion.

Eyewitness accounts from the Lamont family paint a picture of a typical Sunday morning shattered in an instant. Gus, the youngest of three siblings, had been staying with his grandparents, seasoned pastoralists who run a 10,000-hectare sheep station carved out of the Flinders Ranges’ fringes. His parents, Sarah and Tom Lamont, both in their early 30s, were nearby tending to a ewe in labor when the unthinkable happened. “He was right there, playing with his toy truck in the dirt yard,” Sarah recounted in a tearful interview aired on national television late last week. “I turned my back for maybe two minutes to help with the lambing. When I looked again, he was gone. Just… gone.”

The property, a weathered timber homestead flanked by wind-bent gums and rusted windmills, sits miles from the nearest neighbor. No fences breach the horizon, and the nearest sealed road is a 45-minute drive away on unsealed tracks that turn treacherous after rain. Gus was last seen around 9:30 a.m., dressed in a grey akubra hat – a miniature version of the ones his grandfather favors – a blue T-shirt emblazoned with Minions from Despicable Me, his favorite film, and light grey cargo pants. He had no shoes on, which experts say could explain the footprint’s clarity but also heightens fears of dehydration or injury in the thorny undergrowth.

The initial response was swift and overwhelming. Within hours, local police from the South Australia force cordoned off the area, enlisting the State Emergency Service (SES) for ground searches and the Police Air Wing for aerial sweeps. By midday on September 29, over 100 volunteers – neighboring farmers, Indigenous trackers from the local Adnyamathanha community, and even off-duty firefighters – fanned out across the 500-hectare property. Drones equipped with thermal imaging buzzed overhead, while mounted police on horseback navigated the uneven gullies where vehicles couldn’t go. Divers were even called in to scour two nearby dams, though water levels were low and visibility poor.

That first footprint breakthrough came on October 1, a glimmer of hope amid the despair. Found near a cluster of mallee trees, it pointed vaguely eastward, toward a dry watercourse that snakes through the property. Forensic teams cast molds of the print, confirming it matched the tread pattern of a child’s bare foot – no shoes, no socks, just the soft imprint of a small sole against the sun-baked ground. “It was haunting,” admitted one SES volunteer, speaking anonymously to protect the family’s privacy. “Like he’d been there, looking for something, or someone. But then nothing. No scuff marks, no broken branches, no sign of struggle. It’s as if the earth opened up and took him.”

The discovery fueled a surge in activity. Search teams redoubled efforts along the watercourse, using ground-penetrating radar to probe for hidden sinkholes or abandoned mine shafts – relics from the area’s silver mining heyday in the 1880s. Cadaver dogs, imported from Victoria, were deployed, their handlers somber as they navigated the scent trails. One dog alerted near the footprint site, but follow-up digs turned up only rabbit burrows and rusted fence wire. By October 2, the operation had swelled to 300 personnel, with helicopters from the Australian Defence Force joining the fray, their rotors whipping up dust devils that blanketed the horizon.

Yet, as the sun set on the sixth day, the mood has shifted from frantic optimism to a heavy, unspoken dread. On October 3, police announced a scaling back of the active search, transitioning to what they delicately termed a “recovery phase.” Resources would be reallocated, with a smaller team maintaining patrols and a dedicated tip line manned 24/7. “We’ve covered every inch we can with the tools at our disposal,” Stevens explained. “But the outback is vast, and Gus is so small. We’re asking the public to keep sharing his image, to keep the pressure on.”

The Lamont family, thrust into a media storm they never sought, has become a symbol of quiet resilience. Photos of Gus – grinning toothily in one, cradling a lamb in another – were released publicly for the first time on October 2, a desperate bid to jog memories from passing motorists on the Barrier Highway. Sarah, a primary school teacher on leave from her job in Broken Hill, New South Wales, has barely slept, her voice hoarse from pleading appeals. “Gus loves his mummy,” she said in a video posted to a dedicated Facebook group that has amassed over 50,000 members in days. “He calls for me when he’s scared. If you’re out there, baby, hold on. We’re coming.”

Tom, a shearer by trade with callused hands that speak of decades in the wool industry, has shouldered the brunt of coordinating with authorities. The couple’s older children, seven-year-old Mia and five-year-old Jack, have been shuttled to relatives in Adelaide, shielded from the grim reality. Grandparents Reg and Ellen Lamont, both in their 70s, remain at the homestead, their faces etched with grief. “We’ve lived here 40 years,” Reg told reporters clustered at the gate. “Never lost a stock animal we couldn’t find. But a child… that’s different. That’s our blood.”

The case has ignited a firestorm of speculation online, with social media awash in theories ranging from the plausible to the paranoid. Some whisper of wild dogs – dingoes that prowl the ranges in packs – though experts dismiss this, citing no signs of predation. Others float darker notions: abduction by opportunistic drifters along the Stuart Highway, or even involvement from within the family circle. A family friend, speaking out on October 4, issued a fierce rebuke. “These cruel rumors about foul play are tearing us apart,” said the friend, who asked not to be named. “The Lamonts are good people. Focus on helping, not hurting.”

Local Indigenous elders from the Adnyamathanha nation have lent their traditional knowledge to the search, sharing stories of the land’s “songlines” – ancient pathways that guided their ancestors through the desert. One elder, speaking at a community vigil in Yunta’s lone pub, described the outback as “a place that hides what it doesn’t want found.” Ceremonial smokes were lit at the homestead, blessings invoked to call Gus home. “The spirits know where he is,” the elder said. “We just need to listen.”

Across South Australia, the outpouring of support has been staggering. The hashtag #BringGusHome trended nationwide on October 3, with celebrities like actor Hugh Jackman and cricketer Pat Cummins sharing Gus’s photo. In Adelaide, a convoy of 200 vehicles formed a “light parade” on October 4, headlights piercing the night as drivers honked in solidarity. The simple plea – “Leave a light on for Gus” – has become a mantra, porch lights flickering from Perth to Sydney in a chain of human warmth against the cold vastness.

Schools in the mid-north have incorporated the story into lessons on bush safety, emphasizing the “stick together” rule for children in rural areas. Experts from the Australian Institute of Criminology have weighed in, noting that child disappearances in remote regions often stem from misadventure rather than malice – wandering off in pursuit of a butterfly or a lost toy. “The footprint suggests he moved under his own steam,” said child psychologist Dr. Liam Harper in a radio interview. “Gus might have been chasing a kangaroo joey or exploring a new gully. But six days without water… it’s a race against biology now.”

As night falls on October 5, the homestead stands sentinel under a canopy of stars, its windows aglow with that promised light. Volunteers linger in the yard, sipping tea from thermos flasks, unwilling to abandon hope entirely. Somewhere in the whispering scrub, that single footprint endures – a fragile testament to a boy’s fleeting presence, a haunting echo urging the world not to forget. For the Lamonts and the nation holding its breath, the hunt for Gus is more than a search; it’s a vigil for innocence reclaimed from the wild.

In the end, whether miracle or tragedy awaits, this story has reminded Australia of its dual soul: a land of breathtaking beauty laced with peril, where communities forge unbreakable bonds in the face of the unknown. Gus Lamont, with his Minions shirt and boundless curiosity, has touched hearts far beyond the outback’s red horizon. And as long as one light burns, so does the flicker of possibility that he’ll come toddling back, dust-caked and smiling.

News

Highway of Heartbreak: A Stepfather’s Agonized Cry Echoes the Senseless Loss of 11-Year-Old Brandon Dominguez in Las Vegas Road Rage Nightmare

The morning sun crested over the arid sprawl of Henderson, Nevada, casting long shadows across the Interstate 215 Beltway—a concrete…

House of Horrors: The Skeletal Secret of Oneida – A 14-Year-Old’s Descent into Starvation Amid Familial Indifference

In the quiet, frost-kissed town of Oneida, Wisconsin—a rural pocket 15 miles west of Green Bay where cornfields yield to…

Shadows Over Moselle: Housekeeper’s Explosive Theory Challenges the Murdaugh Murder Narrative

In the humid twilight of rural South Carolina, where Spanish moss drapes like funeral veils over ancient live oaks, the…

A Tragic Plunge into the Tasman: The Heartbreaking Story of a Melbourne Man’s Final Voyage on the Disney Wonder

The vast, unforgiving expanse of the Tasman Sea, where the Southern Ocean’s chill meets the Pacific’s restless churn, has long…

DNA Traces and Hidden Horrors: Shocking Twists Emerge in Anna Kepner’s Cruise Ship Death Investigation

The gentle sway of the Carnival Horizon, a floating paradise slicing through the Caribbean’s azure expanse, masked a sinister undercurrent…

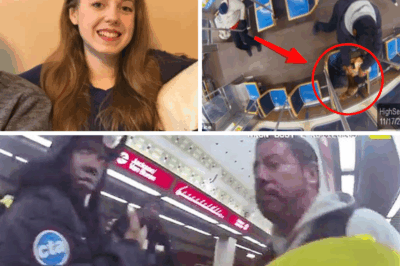

Inferno on the Blue Line: Eyewitnesses Recount the Agonizing Seconds as Bethany MaGee Became a Living Flame

The fluorescent hum of Chicago’s Blue Line train, a nightly lullaby for weary commuters, shattered into primal screams on November…

End of content

No more pages to load