In the cradle of the Australian outback, where the red earth cradles secrets as vast as the sky and the wind carries whispers of the unrecoverable, the disappearance of four-year-old August “Gus” Lamont has etched itself into the nation’s soul like a scar from a thornbush. Ten days after the freckle-faced toddler vanished from his family’s remote sheep station near Yunta, the search has withered into a quiet recovery effort, leaving behind not just an empty mound of play dirt, but a single, shattering sentence that replays in the mind of his mother like a looped lullaby: “I’ll have fun at Nana’s, Mom—don’t worry.” Uttered with the guileless certainty of a child clutching a stuffed kangaroo, those five words—simple, trusting, eternal—were the last Sarah Lamont heard from her “little digger.” As the Flinders Ranges stand sentinel over Oak Park Station, casting long shadows on a grief that defies the dawn, the question hangs heavier than the dust: How does a mother, a family, a community claw their way through the abyss when the final echo is one of pure, unshadowed joy?

The innocence of that farewell lingers like the scent of eucalyptus after rain, a poignant counterpoint to the nightmare that swallowed it. It was Friday, September 26, the day before the world tilted on its axis for the Lamonts. Sarah, 38, a veterinary nurse whose days blurred between clinic shifts in Broken Hill and weekend escapes to the family station, had driven the three-hour haul from town with Gus and his siblings—8-year-old Ella and 6-year-old Jack—in tow. The kids, wired from the road trip’s promise of open paddocks and Nana’s scones, tumbled out of the ute amid a chorus of excited squeals. Gus, ever the independent sprite with his mop of sandy curls and a grin that could coax a smile from a stone, had scampered ahead, backpack slung over one shoulder like a pint-sized explorer. As Sarah unloaded the boot—grocery bags bulging with damper flour and vegemite—he tugged at her jeans, blue eyes wide with that four-year-old earnestness. “Mom, I’ll have fun at Nana’s—don’t worry,” he chirped, planting a sticky kiss on her knee before bolting toward the homestead’s veranda, where Maggie Hargreaves waited with open arms.

Sarah replayed it later, in the sterile hush of a hospital waiting room or the dim glow of a vigil candle, wondering if she’d savored it enough. “It was so him,” she confides now, her voice a fragile thread in the homestead’s kitchen, where the air still holds the faint tang of roast lamb from that last family tea. “No fears, no fuss—just pure light. He hugged me tight, like he knew I’d need it to hold onto.” Tom Lamont, 42, the station’s steadfast overseer with hands roughened by wire fences and wool shears, nods from across the scarred pine table, his eyes distant. “Our boy was built for this life—fearless in the dirt, kind to the lambs. That goodbye… it’s what keeps us breathing, even when it rips us open.” The words, unremarkable in the moment, have since become a talisman: etched on memorial ribbons, whispered in prayers at Yunta’s roadside chapel, and scrawled in chalk on the pub’s blackboard—”Gus’s Promise: Fun Awaits.”

By Saturday afternoon, September 27, the promise curdled into terror. Around 5 p.m., as the sun slanted golden across the 10,000-hectare expanse of Oak Park—its mallee trees gnarled like ancient fingers, its dry creeks mere ghosts of wetter seasons—Gus was last glimpsed by Maggie, knee-deep in a mound of red soil from recent repairs. Clad in a blue Minions T-shirt (a hand-me-down from Jack, emblazoned with the yellow mischief-makers), light grey pants tucked into boots, and a broad-brimmed hat against the glare, he waved his shovel like a scepter, erecting an empire of dirt clods. Maggie, 68, the widow whose unyielding spirit had shepherded three generations through droughts and deluges, had turned away for a mere 30 minutes to tend a ewe in the nearest paddock. “Stay put, digger,” she’d called, her heart light with the rhythm of routine. But when she returned at 5:30, the mound mocked her empty—Gus’s castle half-formed, his laughter silenced by the gathering dusk.

Panic ignited like dry spinifex. Sarah, inside prepping veggies for the evening barbie, rushed out at Maggie’s frantic summons, her knife clattering to the floor. Tom, returning from the troughs on his quad bike, joined the fray, his shouts—”Gus! Mate, where are ya?”—carrying over the ewes’ indifferent bleats. The siblings, ushered indoors with assurances masking dread, pressed faces to the window glass. Flashlights bloomed in the twilight as the family fanned out: under the veranda’s clutter of boots and billycans, behind the shearing shed’s rusted flanks, along the faint track to the windmill where Gus once “fished” for tadpoles. By 7 p.m., with night cloaking the horizon like a funeral veil, Tom gripped the satellite phone and dialed triple zero, his voice cracking: “My four-year-old’s gone missing—Oak Park Station, south of Yunta. Send everything.”

South Australia Police answered the call with outback urgency, their response ballooning into Operation Red Dirt—a colossal endeavor that mobilized 300 souls at its zenith. Utes and helicopters converged on the unsealed gravel track, kicking up plumes that gilded the stars. SES volunteers in hi-vis swarmed the grids, Indigenous trackers from the Adnyamathanha people read the land’s subtle script—scuffed pebbles, bent grasses—while cadaver dogs strained leashes toward phantom scents. ADF choppers thumped from Adelaide, their thermal cams scanning for heat blips amid the cooling earth; drones buzzed like mechanical cicadas, mapping sinkholes and shafts from the silver-rush ghosts of the 1880s. Divers plumbed the dams’ murky hearts, environmentalists charted flash-flood gullies, and psychologists encircled the Lamonts like a human hedge against collapse. For five days, hope flickered: a solitary footprint, child-sized and 500 meters out in a spinifex clump, teased a path northeast. “It matches his boots,” Superintendent Mark Syrus declared, fueling #FindGus to 5 million posts, with PM Anthony Albanese halting a summit to plead for sightings.

But by October 3, the footprint crumbled under forensics—no tread sync, likely a goanna’s pad or a volunteer’s slip—plunging the effort into recovery’s grim hush. Assistant Commissioner Ian Parrott, face etched with the weight of impossible odds, addressed Yunta’s hall: “No trace after 168 hours, in 35-degree days and sub-zero nights… medical experts say survival’s improbable.” The scale-back left the station echoing: helicopters grounded, grids abandoned, volunteers dispersing with sunburns and shattered resolve. Online sleuths spawned cruelties—conspiracies fingering the family, trolls dredging custody whispers—but locals like Fleur Tiver, 66, whose clan neighbored the Lamonts since the 1800s, rallied fierce: “They’re salt-of-the-earth—kind, true. Leave ’em to grieve.”

For Sarah, the void is a living wound, Gus’s words a double-edged blade that comforts and cleaves. In the homestead’s front room, where his toys lie untouched—a plastic ute mid-track, a Minions puzzle half-solved—she curls with his kangaroo plush, inhaling its faint milk-and-dirt scent. “Those words… they’re my anchor and my anchorite,” she murmurs, tears tracing paths down cheeks hollowed by sleepless vigils. The finality hits in waves: no body to bury, no closure to claim, just absence amplified by the outback’s indifference. How to surmount it? Psychologists from Adelaide’s rural outreach, arriving weekly in a dusty LandCruiser, guide her through the stages—denial’s fog yielding to anger’s gale—but theory buckles against the raw. “It’s not stages,” Sarah snaps gently, “it’s a storm that circles back.”

Grief’s alchemy begins in fragments, pieced from community clay. Tom, channeling his grazier’s grit, has transformed the shearing shed into a war room: maps pinned with red string, a ledger of tips from the hotline’s 8,000 calls. “We search on,” he vows, even as private eyes—funded by a GoFundMe cresting $450,000—probe the ranges’ fringes. The siblings, Ella and Jack, navigate with crayon resilience: Ella’s journals brim with “letters to Gus” (“Come home for damper, bro”), Jack’s nightmares soothed by stories of “Nana’s fun adventures.” Maggie, self-flayed by her brief absence, finds solace in the ewes—milking at dawn, whispering confessions to the lambs: “I turned away, but love don’t.” Family friends shuttle in from Broken Hill, bearing lasagnas and levity: barbie nights under the gums, where tales of Gus’s escapades—once “rescuing” a joey from a fence—elicit laughs amid the lump in throats.

Broader lifelines weave through faith and fellowship. Sarah, raised in the saltbush chapels of rural Methodism, clings to Psalms 34:18—”The Lord is close to the brokenhearted”—recited at the station’s makeshift altar, a eucalyptus cross hung with Gus’s hat. Yunta’s pub, the Royal Exchange, has morphed into a grief guild: punters swapping shifts at the homestead, locals like Ray Donovan logging ute-kilometers on “Gus patrols.” Survivalist Michael Atkinson, runner-up on Alone Australia, bucks the odds with bushcraft tips: “Kids hunker in thickets—train dogs on his scent anew.” Online, #GusStrong surges with virtual hugs, but Sarah mutes the noise, curating a private album of his giggles—voicemails of “Mom, look what I found!” beamed from the clinic.

Healing’s horizon, though, demands deliberate strides. Counselors prescribe “legacy rituals”: Sarah plants a spinifex garden by the mound, each sprout a nod to Gus’s castles; Tom etches his words on a homestead plaque—”Fun Awaits”—a beacon for Ella and Jack’s play. Experts from the Australian Centre for Grief and Bereavement advocate “continuing bonds”: talking to Gus at dusk, as chimps hoot in the ranges, or channeling his spirit into advocacy—pushing for satellite trackers on remote stations, subsidies for play-safe fencing. “Pain doesn’t vanish,” one therapist notes, “but it transmutes—into purpose, memory’s fierce guardian.” For Sarah, it’s tentative: journaling the ache, yoga under the stars to reclaim her breath, a vow to “worry less, hug more” with the living.

As October’s chill bites the paddocks, the outback seems to lean in, its vastness a mirror to the heart’s expanse. No miracle unearthed Gus—no footprint path, no dam’s secret—but his words endure, a child’s covenant against despair. Sarah, rocking on the veranda at twilight, gazes where he last waved: “You had fun, didn’t you, buddy? And we’ll find ours again—for you.” The Lamonts, forged in this forge of loss, teach a hard-won truth: surpassing sorrow isn’t erasure, but embrace—carrying the light of “don’t worry” through the gathering dark. In Yunta’s dust-choked dawn, candles flicker anew, not just for the lost, but for the living who loved him whole. Gus Lamont: your fun echoes eternal, guiding the way home.

News

Highway of Heartbreak: A Stepfather’s Agonized Cry Echoes the Senseless Loss of 11-Year-Old Brandon Dominguez in Las Vegas Road Rage Nightmare

The morning sun crested over the arid sprawl of Henderson, Nevada, casting long shadows across the Interstate 215 Beltway—a concrete…

House of Horrors: The Skeletal Secret of Oneida – A 14-Year-Old’s Descent into Starvation Amid Familial Indifference

In the quiet, frost-kissed town of Oneida, Wisconsin—a rural pocket 15 miles west of Green Bay where cornfields yield to…

Shadows Over Moselle: Housekeeper’s Explosive Theory Challenges the Murdaugh Murder Narrative

In the humid twilight of rural South Carolina, where Spanish moss drapes like funeral veils over ancient live oaks, the…

A Tragic Plunge into the Tasman: The Heartbreaking Story of a Melbourne Man’s Final Voyage on the Disney Wonder

The vast, unforgiving expanse of the Tasman Sea, where the Southern Ocean’s chill meets the Pacific’s restless churn, has long…

DNA Traces and Hidden Horrors: Shocking Twists Emerge in Anna Kepner’s Cruise Ship Death Investigation

The gentle sway of the Carnival Horizon, a floating paradise slicing through the Caribbean’s azure expanse, masked a sinister undercurrent…

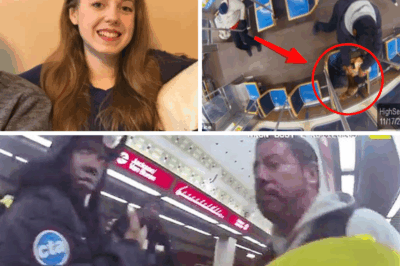

Inferno on the Blue Line: Eyewitnesses Recount the Agonizing Seconds as Bethany MaGee Became a Living Flame

The fluorescent hum of Chicago’s Blue Line train, a nightly lullaby for weary commuters, shattered into primal screams on November…

End of content

No more pages to load