The fluorescent hum of a dispatcher’s headset cut through the winter night like a siren’s wail on February 5, 2007, in the quiet suburbs of Abilene, Texas. It was just past 11:30 p.m., the echoes of Super Bowl cheers still fading from televisions across the Lone Star State, when a young boy’s voice cracked over the line to 911. “My sister… she’s hurt bad,” the caller stammered, his words tumbling in a frantic rush. “I think she’s dying. Help, please!” The dispatcher, seasoned in the grim routine of emergencies, fired off questions: location, injuries, what happened? But the boy’s responses spiraled into something surreal – whispers of a “pumpkin-headed demon” and stabs in the dark. Within minutes, Abilene Police Department officers converged on a modest ranch-style home at 1234 Elmwood Drive, their flashers painting the snow-dusted lawn in staccato blue. What they uncovered inside wasn’t just a crime scene; it was a nightmare etched in a child’s savagery: 4-year-old Ella Bennett lay lifeless in her pink canopy bed, her tiny body bearing the brutal marks of 17 stab wounds, strangled and sexually assaulted by her own brother, 13-year-old Paris Lee Bennett. As the truth unraveled – Paris’s calculated confession, his chilling motive to shatter his mother’s heart – Abilene awoke to a horror that would scar a family, ignite debates on juvenile psychopathy, and echo through true crime chronicles for nearly two decades.

Eighteen years later, the case remains a haunting footnote in Texas’s annals of familial tragedy, resurfacing this month with the premiere of HBO’s “Fractured Bloodlines,” a three-part docuseries that peels back layers of generational trauma. Directed by Emmy-winner Katie Green, the film interweaves archival footage – grainy 911 tapes, courtroom sketches, Paris’s eerily composed interviews – with intimate confessions from Charity Lee Bennett, the mother caught in the crossfire of her son’s rage. “I birthed two miracles and a monster,” Charity, now 48, reflects on camera, her voice a fragile thread amid the ruins. “Ella was my light; Paris, the eclipse.” The series, which debuted to 2.3 million viewers on September 15, has reignited national fascination, drawing parallels to cases like the Menendez brothers or Eric Smith, while probing deeper: Can evil be inherited? And in a state that tried Paris as an adult, where does redemption end and retribution begin?

The Bennett home, a single-story haven in Abilene’s Elmwood neighborhood – a pocket of blue-collar families orbiting Hardin-Simmons University – stood as a testament to Charity’s improbable resurrection. Born in 1977 to a fractured union, Charity’s childhood was a crucible of violence. Her father, James Robert Bennett Jr., a 35-year-old oil rig worker, was gunned down in 1983 in a suspected contract killing orchestrated by her mother, Kyla Claar Bennett, then 32. Kyla, a former beauty queen turned homemaker, was charged with conspiracy to murder but acquitted in a controversial 1984 trial marred by botched forensics and a star witness’s recantation. Charity, just 6, testified tearfully, her small hand clutching a teddy bear as she described the “angry whispers” in the house. Acquitted but ostracized, Kyla spiraled into isolation, leaving Charity to navigate foster homes and a gnawing conviction: “Mom did it. I saw the shadow in her eyes.” By 15, Charity plunged into heroin’s haze, a suicide pact with the needle her escape. But a month shy of her self-imposed deadline, a pregnancy test upended her despair. Paris arrived on October 10, 1993 – a colicky infant with Charity’s dark curls and a cry that pierced her resolve. “He saved me,” she later wrote in her 2017 memoir, My Perfect Child. Sobriety bloomed; by 18, she was a certified nursing assistant, piecing together a life from night shifts and NA meetings.

Ella Christina Bennett entered the world on March 15, 2002, a towheaded cherub with dimples that melted strangers at the grocery store. Charity, now 25 and remarried briefly to a welder named Travis Lee (divorced by 2005), doted on her daughter as the balm to Paris’s growing tempests. Paris, a straight-A student at Bowie Junior High, masked his maelstroms behind a precocious charm – debating teachers on quantum physics, devouring Nietzsche at 11. But fissures cracked early: at 9, he strangled the family cat during a tantrum; at 10, he menaced classmates with a pocketknife, whispering threats of “eternal sleep.” Charity chalked it to “boyish energy,” enrolling him in counseling that he manipulated with feigned remorse. “He was my golden boy,” she confessed in the HBO series. “Smart as a whip, but his eyes… sometimes they’d go vacant, like staring through you to hell.” Relapse loomed in 2004 when Travis’s infidelity shattered the home; Charity turned to cocaine for six months, leaving Paris, then 11, to diaper Ella and microwave her bottles. “I was the parent,” Paris later sneered in a 2019 Piers Morgan interview. “Mom chose powder over us. That debt? I’d collect.”

Super Bowl Sunday, February 4, 2007, dawned deceptively ordinary. Charity, 29 and thriving as a server at Buffalo Wild Wings, pulled a double shift for the game’s frenzy – wings flying, tips stacking. Paris and Ella stayed home with 19-year-old babysitter Alyssa McCall, a neighbor’s daughter earning gas money. Paris, lanky in his Huskies hoodie, played the dutiful brother: helping Ella color unicorns, sharing SpongeBob reruns. But as kickoff neared, his mask slipped. Around 10 p.m., with Charity elbow-deep in ranch dressing at work, Paris cornered Alyssa in the kitchen. “Mom called – emergency at the restaurant. She said go home; she’ll text you,” he lied smoothly, his voice a velvet trap. Alyssa, flustered and phone-silent, grabbed her purse and bolted, waving goodbye to a giggling Ella in her princess pajamas. Alone now, Paris paced the dim hallway, his mind a cauldron. Earlier that week, Charity had grounded him for shoplifting – a petty theft of comics from a Walmart – and denied his plea for a PlayStation. “She’ll pay,” he seethed to a mirror. But killing Charity? Too messy, too final. “Hurt her where it bleeds deepest,” he later explained with clinical detachment. Ella – the “princess” who stole Mom’s lap, the rival for every bedtime story – became the proxy.

Sometime before 11:30 p.m., Paris crept into Ella’s room, the nightlight casting ballerina shadows on walls papered in butterflies. She stirred as he loomed, a steak knife pilfered from the drawer glinting in his fist. “Playtime, Ellie,” he whispered, a predator’s lullaby. What followed was a frenzy of unfathomable cruelty: he raped and sexually assaulted the screaming child, then strangled her flailing form before plunging the blade 17 times into her chest, neck, and abdomen. Blood soaked the unicorn sheets; Ella’s final gurgles faded to silence. Paris, splattered and serene, wiped the knife on her teddy bear and dialed 911. “911, what’s your emergency?” the dispatcher prompted. “My sister’s been stabbed,” he gasped theatrically. “I… I saw a demon – pumpkin head, on fire. It was her! I had to stop it!” As instructions for CPR flowed – “Pinch her nose, two breaths” – Paris faked compressions, counting aloud while pacing the bloodied carpet. Officers burst in at 11:42 p.m., finding him curled fetal by the body, feigning catatonia. “The demon’s gone,” he murmured. But his eyes – cold, appraising – betrayed the ruse.

Charity’s phone buzzed at 12:15 a.m. as she wiped down the bar, the Super Bowl’s confetti still virtual on screens. “Ma’am, you need to come to Abilene PD,” the sergeant said, his tone a lead weight. She arrived in her grease-stained polo, collapsing in the lobby as detectives relayed the horror. “Ella? No… Paris?” Charity wailed, her world inverting. Interrogated at headquarters, Paris shed the act like snakeskin. “I did it,” he admitted flatly to lead detective Maria Gonzalez. “Wanted Mom to suffer. Killing Ella? Double hit – baby dead, big brother caged.” Motive crystallized: resentment’s venom, laced with a budding psychopathy that savored control. Gonzalez, a mother of three, later recounted the chill: “He smiled describing the stabs – like recounting a video game level. No tears, just triumph.”

The investigation unfolded with mechanical precision. Forensics confirmed the timeline: Paris’s prints on the knife, semen traces linking the assault, no forced entry – a family implosion. Alyssa’s statement corroborated the manipulation; neighbors recalled Paris’s eerie solitude, once caught dissecting squirrels in the backyard. Psych evals painted a damning portrait: Paris scored off the charts for antisocial personality disorder, with traits of psychopathy – superficial charm, lack of empathy, grandiose self-worth – flagged since age 8. “Homicidal ideation since kindergarten,” one report noted, citing journals where he fantasized “erasing rivals” with household blades. Charity, gutted, revealed the generational echo: her father’s murder, her mother’s acquittal. “Is this the curse?” she sobbed in therapy tapes. Paris, remanded to Taylor County Juvenile Detention, awaited transfer; at 13, Texas law thrust him into adult court for capital murder.

The August 2007 trial in Abilene’s ornate courthouse was a media maelstrom, gavel falling amid flashbulbs and protesters clutching teddy bears emblazoned with “Justice for Ella.” Prosecutor David Montague framed Paris as a “miniature monster,” replaying the 911 tape – his demonic delusions crumbling under cross-examination. “You faked the voices, didn’t you?” Montague pressed. Paris, in a ill-fitting suit, smirked: “Demons are real. I just summoned one.” Defense attorney Laura Parker urged mercy – brain scans showing underdeveloped prefrontal cortex, the “kid brain” defense – but Charity’s testimony sealed fate. “He was my son,” she wept, clutching Ella’s locket. “But he chose this. For me.” On August 17, Judge Sam Medina sentenced Paris to 40 years at the Polunsky Unit – no parole until 2047, when he’ll be 54 – a compromise dodging the death penalty for juveniles post-Roper v. Simmons (2005). “May God forgive what the law cannot,” Medina intoned. Paris, unbowed, quipped to reporters: “See you in 40. I’ll read law books.”

The aftermath cascaded like dominoes of despair. Charity, fired from Buffalo Wild Wings amid whispers, fled Abilene for anonymity in New Mexico, her nights haunted by Ella’s laughter and Paris’s stare. Relapse tempted; instead, she channeled grief into the Ella Foundation, a nonprofit aiding parents of violent children – counseling hotlines, therapy grants, awareness campaigns. “I forgave him,” she wrote in My Perfect Child, a 2017 bestseller blending memoir and manifesto. “Not for him – for me. But contact? No. He’s a black hole.” Paris, now 32, thrives in prison’s peculiar ecosystem: earning a psychology degree via correspondence from Sam Houston State, publishing essays on “empathy engineering” in inmate journals. His 2019 sit-down with Piers Morgan – eyes gleaming, voice velvet – chilled viewers: “Killing Ella? Best decision. Mom’s pain was poetry.” The interview, viewed 15 million times, branded him “America’s Youngest Psychopath.”

Generational ghosts loomed larger in 2017’s “The Family I Had,” Katie Green’s Oscar-nominated doc tracing Charity’s lineage: Kyla’s acquittal, James’s unsolved echoes, Paris’s inheritance. “Violence isn’t viral; it’s vascular,” Green posits, interviewing Kyla – now 70, frail in a Wisconsin trailer – who rasps, “I loved my Robbie. Charity’s wrong.” The film grossed $1.2 million, funding scholarships in Ella’s name. True crime pods like “Crime Junkie” and “My Favorite Murder” dissected it yearly, amassing millions of downloads; Reddit’s r/TrueCrime threads swell with 5,000+ comments, debating nature versus nurture.

Abilene heals haltingly. Elmwood Drive’s home sold in 2008, razed for a park – “Ella’s Meadow,” swings creaking under wildflowers. Annual vigils draw 200, balloons ascending with verses from Psalm 34: “The Lord is close to the brokenhearted.” Charity, remarried to a quiet engineer named Mark, mothers a son, Phoenix, born 2012 – her “phoenix from ashes.” “Ella taught forgiveness; Paris, boundaries,” she says in HBO’s finale, hugging Phoenix amid sunflowers. Paris writes sporadically – letters Charity burns unread. “He’s caged, but free in his mind,” she muses. “I pray for his soul, not his release.”

As October’s chill grips Texas plains, the Bennett saga endures – a cautionary mosaic of love’s fragility and evil’s precocity. Ella, forever 4, smiles from faded photos: dimples defiant. Paris, 32, plots appeals from Polunsky’s steel. Charity, 48, advocates onward, her voice a beacon in the void. In Abilene’s quiet nights, whispers linger: What breaks a child? And can a mother’s grace mend the un-mendable? The 911 call, that panicked prelude to pandemonium, echoes eternally – a boy’s feigned frenzy unveiling a family’s fatal fracture.

News

Highway of Heartbreak: A Stepfather’s Agonized Cry Echoes the Senseless Loss of 11-Year-Old Brandon Dominguez in Las Vegas Road Rage Nightmare

The morning sun crested over the arid sprawl of Henderson, Nevada, casting long shadows across the Interstate 215 Beltway—a concrete…

House of Horrors: The Skeletal Secret of Oneida – A 14-Year-Old’s Descent into Starvation Amid Familial Indifference

In the quiet, frost-kissed town of Oneida, Wisconsin—a rural pocket 15 miles west of Green Bay where cornfields yield to…

Shadows Over Moselle: Housekeeper’s Explosive Theory Challenges the Murdaugh Murder Narrative

In the humid twilight of rural South Carolina, where Spanish moss drapes like funeral veils over ancient live oaks, the…

A Tragic Plunge into the Tasman: The Heartbreaking Story of a Melbourne Man’s Final Voyage on the Disney Wonder

The vast, unforgiving expanse of the Tasman Sea, where the Southern Ocean’s chill meets the Pacific’s restless churn, has long…

DNA Traces and Hidden Horrors: Shocking Twists Emerge in Anna Kepner’s Cruise Ship Death Investigation

The gentle sway of the Carnival Horizon, a floating paradise slicing through the Caribbean’s azure expanse, masked a sinister undercurrent…

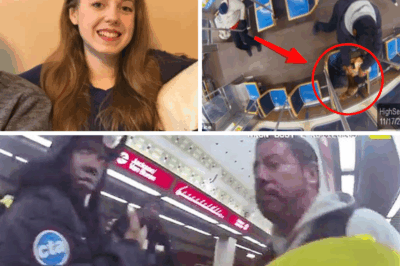

Inferno on the Blue Line: Eyewitnesses Recount the Agonizing Seconds as Bethany MaGee Became a Living Flame

The fluorescent hum of Chicago’s Blue Line train, a nightly lullaby for weary commuters, shattered into primal screams on November…

End of content

No more pages to load