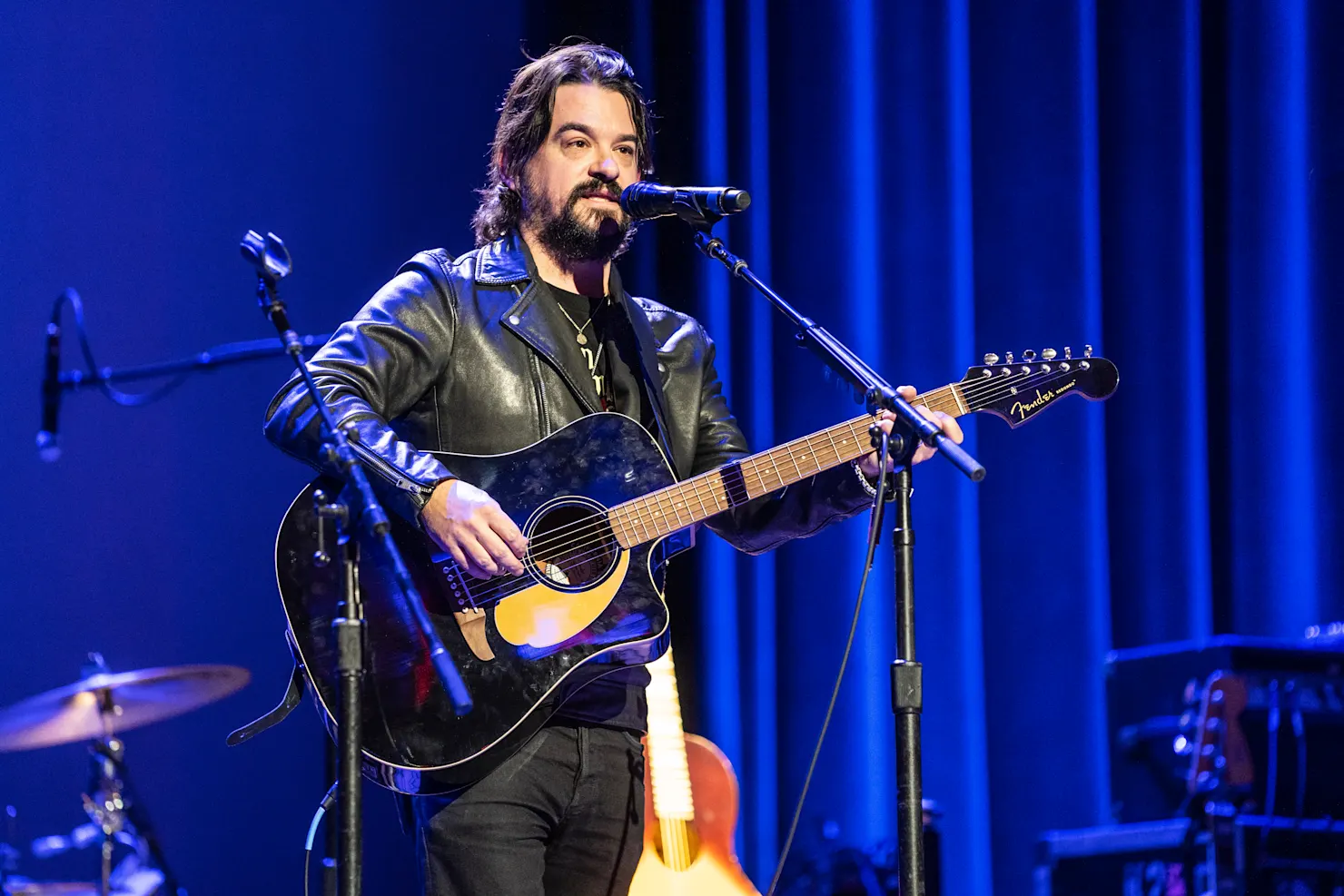

The weight of a name like Waylon Jennings isn’t just carried; it’s worn like a well-scuffed pair of boots—comfortable, battle-tested, and impossible to outgrow. For Shooter Jennings, whose given name is Waylon Albright Jennings III, that legacy has been both a beacon and a burden since his father’s death in 2002. At 45, the Grammy-winning producer and singer-songwriter has spent decades carving his own path in the shadows of the Outlaw Country pioneer who helped redefine the genre with hits like “Luckenbach, Texas (Back to the Basics of Love)” and “Good Hearted Woman.” But now, after sifting through hundreds of dusty multitrack tapes in a Hollywood studio last summer, Shooter is flipping the script: resurrecting his dad’s unreleased recordings from the 1970s and ’80s, a golden era of creative freedom, into a three-album series that promises to peel back the myth and reveal the man. “This isn’t just music,” Shooter told Grok News in an exclusive interview from his Nashville home. “It’s so much heart—conversations frozen in time, full of the gentleness and fire that made Dad who he was.”

The project kicked off quietly in the summer of 2024, when Shooter secured a rare stretch of downtime amid his packed schedule producing albums for artists like Brandi Carlile, Tanya Tucker, and Charley Crockett. Holed up in Studio 3 at Sunset Sound in Los Angeles—now affectionately dubbed “Snake Mountain” in honor of his father’s nomadic spirit—he turned his attention to a backlog of analog tapes transferred to digital drives back in 2008. What started as a casual hunt for a handful of lost tracks ballooned into a treasure trove: over 300 finished songs, demos, and live cuts from Waylon’s prime, recorded between 1973 and 1984 with his tight-knit band, The Waylors, and collaborators like pedal steel wizard Ralph Mooney, songwriter Tony Joe White, and Waylon’s wife (and Shooter’s mom) Jessi Colter. “I thought I’d find maybe five songs to sprinkle into a tribute,” Shooter admitted, strumming idly on a beat-up acoustic that once belonged to his dad. “Instead, it was like opening a time capsule. These weren’t rejects—they were keepers, polished and passionate, just waiting for the right moment.”

The first fruit of this labor, Songbird, dropped on October 3, 2025, via Shooter’s Black Country Rock label in partnership with Thirty Tigers. Clocking in at 10 tracks, the album draws its title from Waylon’s tender cover of Fleetwood Mac’s Christine McVie-penned classic, a gentle ballad that Shooter enhanced with subtle backing vocals from Elizabeth Cook and Ashley Monroe— the only fresh additions to the otherwise archival material. Mixed entirely in analog on a 1976 DeMedio API board—the same vintage gear Waylon would’ve geeked out over—Songbird captures the raw intimacy of sessions laid down after Waylon wrested creative control from RCA Records in a David-vs.-Goliath contract battle. Songs like the wistful “If You See Me Getting Mighty Down on Myself” and the soul-stirring “What Makes a Man Wander” showcase Waylon’s baritone at its most vulnerable, far from the rowdy outlaw persona that dominated headlines. “Dad was always the good guy underneath it all,” Shooter reflected. “These tapes show his soft side—the lover, the dreamer—not just the rebel.”

Production stayed true to the era’s grit. Shooter brought back surviving Waylors—guitarist Gordon Payne, bassist Jerry Bridges, keyboardist Barny Robertson, and vocalist Carter Robertson—to overdub missing parts where original sessions fell short of a full band sound. He comped vocals meticulously in Pro Tools, splicing the best takes from multiple runs, a technique he’d honed on modern records but applied here with reverent care. “It was surreal hearing all those versions of his voice—cracking on the high notes, laughing mid-phrase,” Shooter said. “I treated it like I would any artist: no shortcuts, just soul.” The result? A sonic bridge between decades, where Waylon’s steel guitar weeps over themes of love, loss, and quiet redemption, countering the machismo of his chart-toppers.

This isn’t Shooter’s first dance with his father’s vault. Back in 1996, at just 17, he and Waylon cut Fenixon—a father-son project blending rock edges with country roots—that languished unreleased until Shooter dropped it on Record Store Day in 2014 after remastering chunks for the 2012 posthumous collection Waylon Forever. But Songbird feels different: more personal, more revelatory. Previewed at a star-studded Father’s Day bash on June 16, 2025—at L.A.’s Viper Room, coinciding with Waylon’s 88th birthday—the tracks drew tears from guests like Crockett and Colter. “It was like Dad walked in,” Colter said later, her voice thick with emotion. Shooter performed stripped-down versions onstage, joined by Crockett for a loose “Good Hearted Woman” jam that had the crowd two-stepping through the haze of nostalgia.

Waylon Arnold Jennings, born June 15, 1937, in Littlefield, Texas, was the ultimate self-made maverick. Raised in a dirt-poor family of seven, he dropped out of high school at 14 to DJ at a local Lubbock station, spinning Hank Williams and Lefty Frizzell tunes that would shape his sound. By 1958, he’d traded airwaves for the road, bass in hand as Buddy Holly’s final bandmate—a gig cut short by Holly’s plane crash in February 1959, which left a haunted Waylon vowing to chase the dream harder. Phoenix became his proving ground, where he hustled as a performer and label owner, but Nashville called in 1965. Signed to RCA under Chet Atkins’ watch, Waylon chafed against the “Nashville Sound” polish, growing his hair long and his sideburns wild in defiance.

The Outlaw movement exploded in the mid-’70s, with Waylon and Willie Nelson leading the charge against Music Row’s slick suits. Albums like 1973’s Honky Tonk Heroes and 1976’s Wanted! The Outlaws—the first country platinum seller—cemented his rebel crown, racking up 16 No. 1 singles and 60 million records sold worldwide. Hits like “Mammas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys” (a duet with Nelson) and “Theme from The Dukes of Hazzard (Good Ol’ Boys)” blended honky-tonk swagger with rock ‘n’ roll edge, inspiring generations. But fame’s toll was brutal: decades of cocaine-fueled tours, a 1978 heart scare that forced rehab, and battles with the bottle that strained his marriage to Colter, the “Good Hearted Woman” herself. They wed in 1969 after Waylon’s divorce from his high school sweetheart, weathering storms that tested their bond until his death from diabetes complications at 64.

Shooter entered this whirlwind as the couple’s only child together, born in 1979 amid Waylon’s peak fame. Christened Waylon Albright but nicknamed “Shooter” after a playful quip from actor Dennis Hopper (who joked the kid would “shoot ’em all down” like his old man), he grew up on buses and backstage, absorbing the chaos of stardom. “Dad was larger than life—generous, funny, flawed,” Shooter recalled. “He’d wake me at 3 a.m. for guitar lessons, then crash out till noon. It was magic and madness.” By his teens, Shooter was fronting punk-infused country bands in Lubbock, but Waylon’s shadow loomed. A brief stint in Hierophant, a raw rock outfit, led to his 2005 solo debut Put the ‘O’ Back in Country, channeling Dad’s defiance with tracks like “Electric Rodeo.”

Yet Shooter’s true calling emerged behind the board. Since producing 2010’s The Black Side of the Blue for his own .357’s project, he’s become Nashville’s go-to sonic architect—helming Tucker’s 2019 comeback While I’m Livin’, which snagged a Grammy for Best Country Album, and Crockett’s Lil G.L.’s Blue Bonanza in 2024. “Producing lets me honor the family craft without the spotlight stealing my soul,” he said. Married to actress Misty Brooke since 2013, with two young daughters, Shooter’s life now orbits family dinners and studio marathons, a far cry from the tour-bus nomadism of his youth. “Dad taught me music’s about connection, not conquest,” he noted. “These tapes? They’re that lesson amplified.”

The Songbird rollout has been a fan frenzy. Debuting at No. 3 on Billboard’s Country Albums chart, it’s hailed as “a resurrection that feels like a hug” by Rolling Stone. Social media buzzes with teary testimonials—”Waylon’s voice hits different now, like he’s whispering from heaven,” one X user posted—while radio stations spin the title track nonstop. Shooter teased the sequels at a September Ryman Auditorium listening party: Album two, slated for 2027, dives into Waylon’s experimental side projects; the third, around 2030, unearths live rarities and Colter duets. “It’s a story in three acts,” he explained. “The gentle opener, the wild middle, the reflective close. Fans kept Dad alive; this is my thank-you.”

Critics praise the tenderness unearthed. “These aren’t dusty relics—they pulse with the humanity Waylon guarded fiercely,” wrote The Tennessean. Garden & Gun called it “a shoo-in for year-end lists, countering the outlaw bluster with ballads that bare the soul.” Even skeptics who feared overproduction nod to Shooter’s restraint: no Auto-Tune gloss, just the hum of tape hiss and the crackle of conviction. “I mixed it like Dad would’ve—analog, unfiltered,” Shooter said. “He fought for that freedom; I’m just handing it back to the world.”

For Shooter, the deeper gift is personal. “This project rewrote my relationship with him,” he confessed, flipping through faded Polaroids of Waylon cradling infant Shooter on a tour bus. “I always saw the icon, the fighter. Now? I see the dad who poured his heart into every note, gentle as a lullaby.” As Nashville’s neon flickers outside his window, Shooter eyes the next vault dive. In an industry churning TikTok trends, this son’s revival of his father’s forgotten fire feels timeless—a reminder that true legends don’t fade; they echo, softer and stronger, through the ones they leave behind.

Waylon’s shadow? It’s not so much a burden anymore. For Shooter, it’s become a harmony.

News

Waylon Jennings & Willie Nelson’s “Blackjack County Chains”: The Haunting Prison Ballad That Defined Outlaw Country’s Soul

NASHVILLE — In the dusty annals of outlaw country, where rebels like Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson thumbed their noses…

Cardi B’s Tearful Birth Confession: Stefon Diggs’ Unwavering Support Shows What True Love Really Looks Like

Cardi B has never shied away from the spotlight, but in a raw, emotional moment that’s left fans reaching for…

Rihanna’s Camp Flog Gnaw Surprise: Spotted Cheering A$AP Rocky – But That Eerie Lookalike Shadowing Her in the Crowd Has Fans Spooked

LOS ANGELES — The neon-lit chaos of Tyler, the Creator’s Camp Flog Gnaw Carnival pulsed with electric energy on November…

Tyler Perry’s Beauty in Black S2 Heats Up: Kimmie’s Ruthless Rise Takes Center Stage in Darker, More Twisty Sequel

LOS ANGELES — The glittering underbelly of Atlanta’s beauty empire is about to get a whole lot uglier, as Netflix’s…

Fall for Me 2 Trailer Sparks Romance Revival: Fans Swoon Over Tender Twists and Healing Hearts in Sequel Tease

LOS ANGELES — The sun-kissed shores of Mallorca are calling once more, but this time with a deeper glow of…

Maxton Hall S3 Trailer Tease: Ruby & James’ Long-Awaited Happy Ending – But That Jaw-Dropping Twist Will Shatter It All First

NASHVILLE — The opulent halls of Maxton Hall – The World Between Us are about to echo with one last…

End of content

No more pages to load