It was supposed to be the end of one man’s life. Instead, it became the beginning of a nightmare that claimed 11 others and left nearly 200 maimed in one of the worst rail disasters in modern U.S. history.

On the morning of January 26, 2005, Juan Manuel Alvarez, a 25-year-old factory worker from Compton, drove his gray Jeep Grand Cherokee onto the railroad tracks near Chevy Chase Drive in Glendale. Struggling with severe depression, drug addiction, and a crumbling marriage, Alvarez had slashed his wrists and arms earlier that day. He told investigators he intended to die by train.

But at the final moment — as the Metrolink commuter train barreled toward him at 78 mph — Alvarez changed his mind. He abandoned the vehicle, leaving it straddling the tracks with its hazard lights blinking. Seconds later, the southbound Metrolink Ventura County Line train slammed into the SUV, triggering a catastrophic chain reaction that derailed two trains and turned a quiet suburban rail corridor into a scene of twisted metal and carnage.

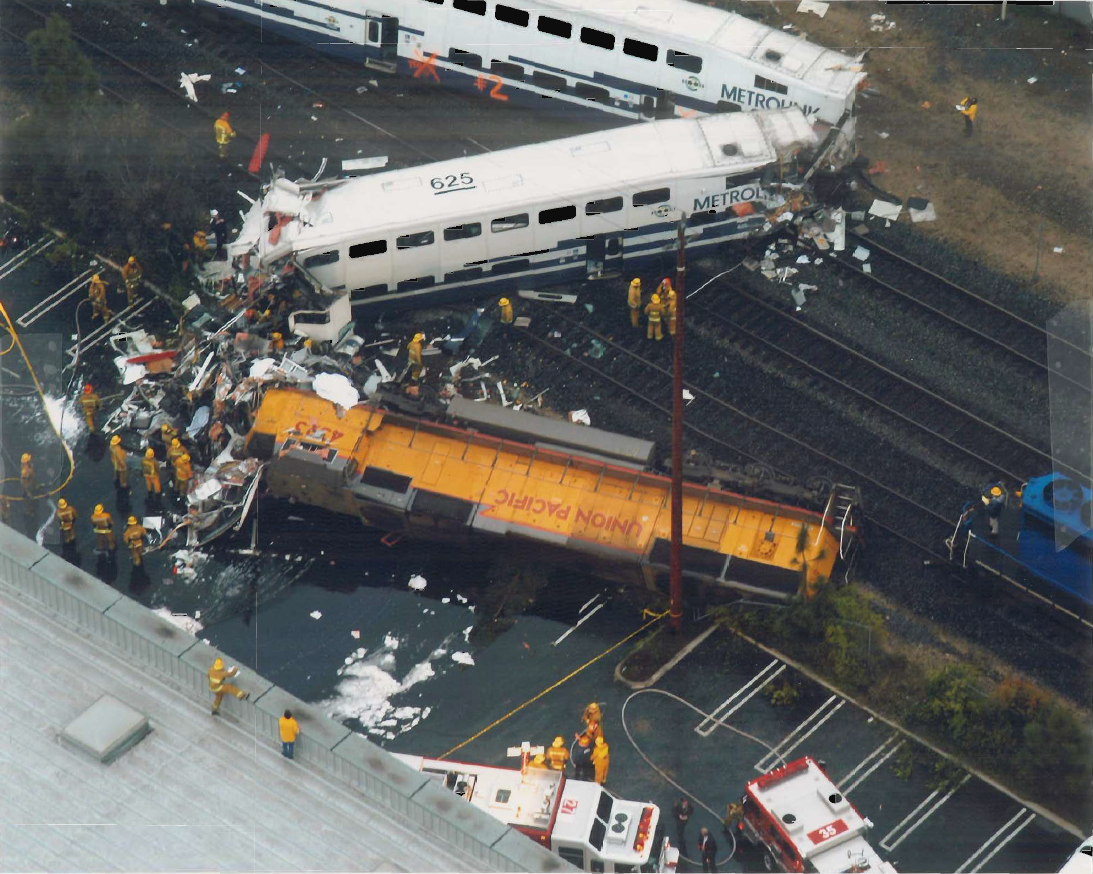

The impact was devastating. The Jeep was hurled 300 feet down the tracks. The lead car of the Metrolink train jackknifed, flipping onto its side and striking a stationary Union Pacific freight train on an adjacent track. That collision caused a second Metrolink train — traveling northbound — to plow into the wreckage moments later. Eleven passengers were killed instantly or died shortly after. Another 177 were injured, many with crushed limbs, traumatic brain injuries, and severe burns from ruptured fuel tanks.

Eyewitnesses described a hellish tableau. “It looked like a bomb went off,” said passenger Maria Lopez, who suffered a broken pelvis. “People were screaming, blood everywhere. I saw a man pinned under a seat, his leg gone.”

First responders faced chaos. Glendale Fire Captain John Breen recalled the smell of diesel and the cries of the trapped. “We had to cut through steel to get to people. Some didn’t make it,” he said.

Alvarez, who fled the scene on foot, was arrested hours later at a friend’s home in Atwater Village. Covered in self-inflicted wounds, he initially claimed the SUV had been stolen. But under questioning, he confessed to parking it deliberately — then panicking and running.

What began as a deeply personal crisis morphed into a public catastrophe with staggering consequences. Prosecutors charged Alvarez with 11 counts of murder with special circumstances, arguing he acted with “depraved indifference” to human life. The case hinged on whether his last-second change of heart absolved him of intent. It did not.

In a trial that gripped Southern California, jurors heard harrowing survivor testimony and saw graphic photos of the derailment site. Alvarez’s defense painted him as a broken man driven by meth-fueled despair. Prosecutors countered that he knew exactly what a vehicle on active tracks would do — especially after dousing the Jeep’s interior with gasoline, which they said showed premeditation.

On June 26, 2006, a Los Angeles County jury convicted Alvarez on all counts. He was sentenced to 11 consecutive life terms without parole — one for each victim. Judge William F. Fahey called the act “an unspeakable tragedy born of cowardice and selfishness.”

The victims were ordinary commuters heading to work or home. Among the dead:

Manuel Alcala, 51, a beloved Glendale police officer and father of three.

Julia Bennett, 44, a nurse returning from a night shift.

Leonard Romero, 38, a construction worker saving for his daughter’s college fund.

Their families packed the courtroom, clutching photos and sobbing as the verdict was read. “He didn’t just kill my husband,” said Alcala’s widow, Rosa. “He stole our future.”

The derailment exposed glaring safety gaps in the rail system. The Metrolink train lacked a “positive train control” (PTC) system — technology that could have automatically slowed or stopped the locomotive. Though mandated after a deadly 2008 Chatsworth crash, PTC was not yet installed in 2005. Critics also pointed to inadequate fencing and signage at the crossing, which had seen prior incidents.

Metrolink responded by accelerating safety upgrades. Within a year, concrete barriers were installed at high-risk crossings, and inward-facing cameras were added to locomotives. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) cited the SUV’s position as the primary cause but recommended enhanced suicide prevention protocols, including better coordination with mental health agencies.

Alvarez’s case became a grim case study in forensic psychology. Experts testified he suffered from borderline personality disorder and chronic methamphetamine psychosis. Yet the jury rejected an insanity defense, finding he understood the consequences when he left the Jeep behind.

From his cell at California State Prison in Lancaster, Alvarez has expressed remorse — but only in limited, court-monitored statements. In a 2010 parole hearing (automatically scheduled despite his life sentence), he said: “I never meant for anyone to get hurt. I just wanted the pain to stop.” The board denied release, calling his actions “among the most reckless in California history.”

The Glendale derailment remains the deadliest incident in Metrolink’s 30-year history. A memorial plaque at the site lists the 11 names beneath a simple inscription: “In memory of those lost, may their light guide us to safer tomorrows.”

Nearly two decades later, survivors still bear the scars. Passenger David Morales, who lost three fingers, told Fox News: “I see that Jeep in my nightmares. One man’s five-second decision ruined hundreds of lives.”

The tragedy also sparked a broader conversation about suicide and public safety. Mental health advocates note that rail suicides are rare but catastrophic when they involve abandoned vehicles. In the U.S., trains kill about 500 people annually — half suicides, half accidents. Yet few cases match Glendale’s body count.

Legal experts say the murder conviction set a precedent. “This wasn’t road rage or a bar fight,” said former L.A. County DA Steve Cooley. “It was a deliberate act that foreseeably endangered dozens. The law demands accountability.”

Today, the Chevy Chase Drive crossing is quiet, flanked by chain-link fences and warning signs. Commuters rush past without a second glance. But for those who remember January 26, 2005, the screech of metal on metal still echoes.

Alvarez, now 45, will die in prison. The 11 families he shattered continue to grieve. And Glendale — a city that prides itself on safety — carries the weight of a morning when one man’s despair ignited a fireball of unintended death.

As one survivor put it: “He walked away. We never did.”

News

Rihanna Responds to a Fan Saying, “They Saying It’s 2016, Rih”: What Her Viral Reply Really Means

When a fan recently commented, “They saying it’s 2016, Rih,” few expected Rihanna to respond. She often ignores random online…

Rihanna’s Unmatched Face Card: How One Look Became a Cultural Phenomenon

Few celebrities command attention the way Rihanna does. Across red carpets, candid street photographs, and unfiltered social media moments, one…

400,000 FRANCS FOR RELEASE: PROSECUTORS SEEK BAIL FOR OWNERS AFTER DEADLY CRANS-MONTANA NEW YEAR FIRE

Prosecutors in Sion have requested a total of 400,000 Swiss francs in bail to grant provisional freedom to Jacques and…

📰 RCMP RELEASES NEW TIMELINE DETAILS IN LILLY AND JACK SULLIVAN CASE AS ALLEGED MESSAGES SPARK FRESH CLAIMS

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has entered another sensitive phase as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police released new…

JUST NOW: Investigators Flag Timeline Issues and Re-Examine Key Details in the Disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has taken an unexpected and unsettling turn, according to the latest update released…

A new wave of controversy erupted online this week after the daughter of an NBA legend reportedly came forward with what she described as troubling information involving Stefon Diggs and his relationship with Cardi B.

According to circulating social-media claims, she suggested that Cardi B should reconsider her involvement with the NFL star, citing alleged…

End of content

No more pages to load