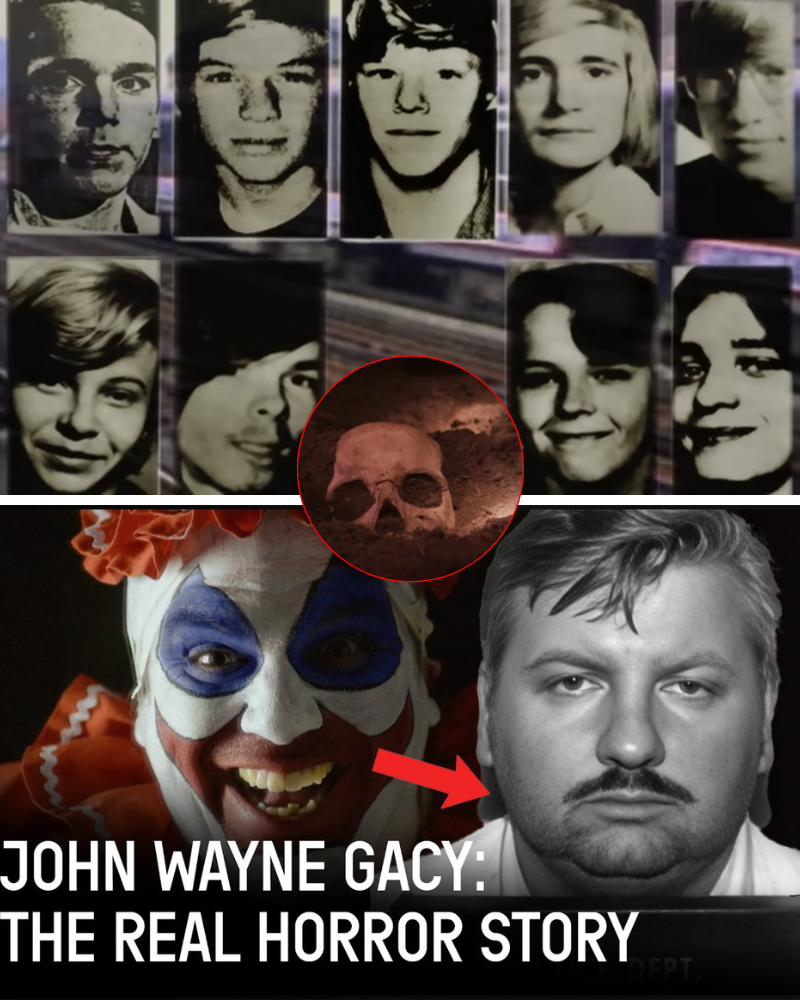

John Wayne Gacy seemed like the epitome of suburban success in 1970s Norwood Park Township, a tidy Chicago enclave where barbecues and block parties defined normalcy. A thriving contractor, Democratic precinct captain, and doting stepfather, he volunteered as “Pogo the Clown” at children’s hospitals and charity bashes, his painted grin a fixture at fundraisers. Neighbors adored him; cops waved hello. But beneath his unassuming ranch house at 8213 West Summerdale Avenue lurked a chamber of unspeakable evil: a crawlspace crammed with the decaying remains of at least 26 young men and boys, strangled or suffocated in rituals of torture that spanned six years. Gacy’s double life – predator by night, pillar by day – unraveled in December 1978 after a desperate teen’s vanishing ignited a probe that exposed one of the most prolific killing sprees in U.S. history. Convicted of 33 murders, he was executed in 1994, but the scars on Chicago’s psyche endure, a grim testament to how charm can cloak monstrosity.

Born March 17, 1942, in Chicago’s working-class Irish enclave, Gacy’s childhood was a pressure cooker of abuse. His father, John Wayne Gacy Sr., a machinist and World War I vet, was a volatile alcoholic who belittled his son relentlessly – calling him a “sissy” and beating him with a razor strop for perceived slights. Young John, overweight and awkward, endured blackouts from head trauma inflicted by his dad, later diagnosed as possible concussions. He also suffered a hushed sexual assault around age 9 by a family friend’s teenage daughter, a trauma that festered unspoken. Despite the hell at home, Gacy graduated high school in 1960 and dove into sales, landing a shoe store gig that took him to Springfield, Illinois. There, he married Marlynn Myers in 1964, a co-worker’s sister, and fathered a son and daughter. He joined the Jaycees, a civic booster club, rising fast as a fundraiser and organizer – traits that would later mask his depravity.

Cracks emerged early. In 1968, Gacy was convicted in Waterloo, Iowa, of sodomizing a teenage boy – one of several he’d lured with booze and cash for “handyman” jobs at a KFC franchise he managed. He pled guilty to multiple counts of aggravated assault and oral sodomy, drawing a 10-year sentence but serving just 18 months at Iowa State Men’s Reformatory. Paroled in 1970, he fled to Chicago, divorcing Marlynn and severing ties with his kids. Undeterred, he rebuilt: his mother co-signed a loan for the Summerdale house, and by 1971, he’d launched PDM Contractors, a remodeling firm that ballooned to 12 employees, many teens he paid under the table.

Gacy’s facade solidified. He remarried Carole Hoff, a high school sweetheart and mother of two girls, in 1972, blending their families into a Brady Bunch parody. He hosted lavish barbecues, complete with fireworks and a Ferris wheel, earning nods from local pols like Mayor Jane Byrne. In 1975, he joined the Jolly Joker Clown Club, crafting costumes for “Pogo” and “Patches” – alter egos that let him “regress to childhood,” as he’d later boast. He’d entertain at parades, hospitals, and his own holiday bashes, snapping Polaroids with beaming kids while donating to Democrats and the Moose Lodge. “Clowns can get away with murder,” he quipped once to detectives – a slip that chilled in hindsight.

The killings likely started in 1972, though Gacy claimed his first was 1974. He targeted runaways, hustlers, and job-seekers from Chicago’s North Side – vulnerable youths advertising in the classifieds or loitering at the Greyhound station. Lured by offers of $50 for quick construction gigs or porn peeks in his “boy’s room” – a den stocked with bondage gear and Playgirl mags – victims entered willingly. Inside, the trap snapped: chloroformed rags, handcuff tricks (“Want to try the psychology test?”), and hours of rape, torture with candles and whips. Many were strangled with their own underwear or a garrote fashioned from floorboard splinters; four were injected with chloroform until they asphyxiated. Bodies went to the crawlspace, doused in lime to curb the stench, or the Des Plaines River when space ran out.

Early red flags waved ignored. In 1972, a teen accused Gacy of battery; charges vanished after Gacy cried blackmail. Carole smelled decay by 1975, spotting the crawlspace’s fresh soil, but Gacy blamed “sewer rats.” Employees griped about the odor; one, John Butkovich, confronted Gacy over back pay in 1976 and vanished – his Plymouth found abandoned. Parents of missing sons – like 15-year-old John Butkovich and 16-year-old Gregory Godzik – begged cops to raid Gacy’s address, but Des Plaines PD dismissed them, swayed by his clout. “He’s a good guy,” officers parroted, blind to the pattern of 18 missing boys from 1972-1978.

The dominoes toppled with Robert Piest, a 15-year-old bagging groceries at Nisson Pharmacy on December 11, 1978. Gacy, bidding on a remodel job, promised Piest $50/hour for summer work and lured him to his van. Piest never returned. His mom, Elizabeth, alerted Des Plaines detectives, who learned of Gacy’s shady rep from prior complaints. Lt. Joseph Kozenczak, a no-nonsense investigator, surveilled Gacy’s home, noting the parade of young men and the eerie clown murals.

A survivor cracked it open: 27-year-old Jeffrey Rinaldi, a hustler Gacy had handcuffed in 1978, escaped by talking his way free and bolted to cops with tales of the “boy’s room.” Armed with a search warrant, Kozenczak’s team raided December 13, 1978. The crawlspace reeked of death; officers unearthed five bodies that night, including Butkovich’s, identified by a high school ring. Divers dredged the Des Plaines for four more – John Premium, Michael Bonnin, Robert Gilpatric, and John Mowery – strangled and weighted with concrete. Over weeks, the tally hit 29: 26 in the crawlspace, two in the attic, five in the river. Piest’s body surfaced April 1979, chloroformed and river-dumped. Dental records and X-rays ID’d most; four remain unnamed, etched as “Jane Does” on a memorial plaque.

Gacy’s arrest imploded his empire. He confessed to detectives – with caveats – claiming “they” (a shadowy ring) forced the kills, or victims died in rough sex gone wrong. His trial, starting February 1980 in Chicago’s Cook County Courthouse, was a media circus. Prosecutor Terry Sullivan hammered the evidence: ropes, photos of bound boys, a police photo of Gacy grinning in his Pogo suit post-arrest. Defense attorney Sam Amirante argued insanity, trotting out shrinks who deemed Gacy a multiple personality – one benign, one “Jack.” Jurors bought none of it. On March 13, 1980, they convicted him on 33 felony murder counts, plus sex offenses. Judge William Kunkle sentenced him to death for 12, life for 21 – “The most appropriate penalty for the most appropriate crime,” Kunkle intoned.

Appeals dragged 14 years, Gacy whiling time on death row at Menard Correctional Center, painting clown portraits – including himself as Pogo – that fetched $1,200 a pop from gawkers. He blamed everyone: cops, gays, his victims. On May 10, 1994, at Stateville, he got lethal injection – last words a flippant “Kiss my ass.” Witnesses included victims’ kin; Sullivan watched, closure etched on his face.

The fallout reshaped Chicago. Norwood Park families fled the tainted block; the house demolished in 1979, its site a vacant lot warded by prayers. Gacy’s clown gigs scarred coulrophobia into pop culture – think Stephen King’s Pennywise. Netflix’s 2022 “Conversations with a Killer” tapes revived the horror, featuring Gacy’s oily denials. Victims’ families, like Piest’s, fought for memorials; DNA in 2017 ID’d John Doe No. 24 as James Byron Haakenson, 16, from Minnesota. Three more bones await matches.

Gacy’s saga warns of unchecked privilege: a white, wealthy everyman evading scrutiny while minorities vanished without trace. Kozenczak, who cracked the case against brass pushback, retired a hero. Today, as true-crime binges glorify the ghoul, the real ghosts are the boys – hustlers and dreamers snuffed by a monster in makeup. In Norwood Park’s quiet streets, Pogo’s laugh echoes faint, a clown’s curse on complacency.

News

Rihanna Responds to a Fan Saying, “They Saying It’s 2016, Rih”: What Her Viral Reply Really Means

When a fan recently commented, “They saying it’s 2016, Rih,” few expected Rihanna to respond. She often ignores random online…

Rihanna’s Unmatched Face Card: How One Look Became a Cultural Phenomenon

Few celebrities command attention the way Rihanna does. Across red carpets, candid street photographs, and unfiltered social media moments, one…

400,000 FRANCS FOR RELEASE: PROSECUTORS SEEK BAIL FOR OWNERS AFTER DEADLY CRANS-MONTANA NEW YEAR FIRE

Prosecutors in Sion have requested a total of 400,000 Swiss francs in bail to grant provisional freedom to Jacques and…

📰 RCMP RELEASES NEW TIMELINE DETAILS IN LILLY AND JACK SULLIVAN CASE AS ALLEGED MESSAGES SPARK FRESH CLAIMS

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has entered another sensitive phase as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police released new…

JUST NOW: Investigators Flag Timeline Issues and Re-Examine Key Details in the Disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has taken an unexpected and unsettling turn, according to the latest update released…

A new wave of controversy erupted online this week after the daughter of an NBA legend reportedly came forward with what she described as troubling information involving Stefon Diggs and his relationship with Cardi B.

According to circulating social-media claims, she suggested that Cardi B should reconsider her involvement with the NFL star, citing alleged…

End of content

No more pages to load