In the golden haze of a late summer afternoon on August 23, 1957, Dorothy Miller stepped onto the platform at Chicago’s bustling Union Station, her floral dress fluttering like a flag of optimism in the wind. At 32, she was the picture of mid-century poise: auburn hair pinned in soft waves, a modest pearl necklace glinting against her collarbone, and a small leather valise clutched in one manicured hand. She turned, waved goodbye to her tearful family clustered on the concourse—her husband Robert, her young daughter Ellen, and her widowed mother, Clara—and boarded the westbound California Zephyr, Amtrak’s crown jewel of rail travel, bound for a fresh start in San Francisco. The train’s whistle pierced the air like a promise, steam billowing as it pulled away from the city that had broken her heart. That wave, captured in a faded family snapshot, was the last tangible trace of Dorothy Miller. She vanished into the iron veins of America, leaving behind a void that would swallow decades, baffle generations of investigators, and etch her name into the annals of unsolved mysteries. For 67 years, her disappearance haunted a family fractured by grief, fueled tabloid frenzies, and mocked the era’s faith in progress and safety. When the truth finally clawed its way to the surface in 2024—a revelation born from a dusty attic trunk and cutting-edge forensics—it wasn’t the triumphant homecoming anyone dared dream of. It was more disturbing, more heartbreaking than the wildest theories: a tale of quiet desperation, unspoken betrayal, and the darkest secrets that fester in the safest of journeys. Dorothy Miller didn’t just disappear; she was erased, her story a grim testament that even the gleaming rails of the American Dream can lead to oblivion.

To unravel the enigma of Dorothy’s vanishing, we must first step into the sepia-toned world of 1950s America, where the train was king—a symbol of mobility, romance, and reinvention. The California Zephyr, launched in 1949, was the pinnacle of rail glamour: Vista-Domes offering panoramic views of the Rockies, club cars alive with cocktail chatter, and sleeping berths that whispered of adventure. For Dorothy, a schoolteacher from the working-class suburbs of Evanston, Illinois, it represented escape from a life unraveling at the seams. Married at 19 to Robert Miller, a stoic auto mechanic with a penchant for Pabst Blue Ribbon and poker nights, Dorothy had once dreamed of classrooms beyond the Windy City. She and Robert had met in high school, bonded over sock hops and shared ambitions, and welcomed Ellen in 1945 amid the victory parades of V-J Day. But by 1957, the fairy tale had curdled. Robert’s long hours at the garage masked a growing distance; whispers of late-night “overtime” with a barmaid named Lorraine circled like vultures. Dorothy, ever the stoic Midwesterner, confided in letters to her sister: “The house feels like a cage, Rob like a stranger. San Francisco calls—clean air, new lessons to teach.” Her mother Clara, a widow since the Great Depression claimed her father, urged caution, but Dorothy’s spirit—fueled by Kerouac’s On the Road and the era’s post-war wanderlust—won out. She secured a teaching post at a progressive elementary in the Bay Area, packed her valise with sheet music, a locket from Ellen, and a dog-eared copy of The Feminine Mystique (avant la lettre), and boarded the Zephyr with $200 in her purse and hope in her heart.

The initial hours were unremarkable, a postcard of rail travel’s allure. Witnesses—fellow passengers sipping Manhattans in the diner car—recalled Dorothy as “a quiet beauty, reading poetry by the window, smiling at the prairie sunsets.” She chatted with a traveling salesman about the merits of Eisenhower’s highways, shared a laugh with a young mother over teething remedies, and penned a postcard to Ellen: “The land stretches like a promise, darling. Mama’s coming home soon, with stories for your dolls.” The train chugged westward, crossing Illinois cornfields into Iowa’s rolling hills, the rhythm of the rails a lullaby against the unknown. By nightfall, as it pierced the Missouri River at dusk, Dorothy retired to her lower berth in Car 7, the Silver Chasm—a cozy nook with crisp linens and a velvet curtain for privacy. The conductor, grizzled veteran Harold Jenkins, punched her ticket with a nod: “Sweet dreams, ma’am. We’ll see the mountains by dawn.” That was the last confirmed sighting. When the Zephyr pulled into Denver at 7:42 a.m. on August 24, Dorothy’s berth lay empty—bed made, valise gone, but no trace of its occupant. Panic rippled through the crew: a frantic search of the cars, the platforms, even the freight holds. Nothing. The FBI was called by noon; headlines screamed “MOTHER OF ONE VANISHES ON TRANS-CONTINENTAL LINER” in the Chicago Tribune. Robert arrived by evening train, his face ashen, clutching Ellen’s hand like a lifeline. “She wouldn’t leave us,” he stammered to reporters. “Not without a word.” But doubt crept in like fog off the Platte River—had Dorothy jumped? Been pushed? Or simply stepped off into the ether?

The investigation ignited like a match in dry tinder, a media circus that gripped the nation for months. The era’s true-crime obsession, fresh off the Black Dahlia fixation, devoured the story: Life magazine splashed “The Ghost Train Widow” across its cover, speculating on foul play amid the Zephyr’s “floating hotel” anonymity. Detectives combed the route: interviewing 347 passengers (a traveling evangelist claimed to have seen “a woman in distress near the observation deck”), scrutinizing crew logs (Jenkins swore “no stops unaccounted for”), and dredging streams for her body (yielding only a rusted hubcap). The FBI’s file, declassified in 1985, ballooned to 1,200 pages: polygraphs for Robert (he passed, but sweatily), tips from psychics (one “saw” her in Reno’s casinos), and wild theories—a communist abduction tied to the Red Scare, or a botched robbery by train-hoppers. Dorothy’s circle yielded crumbs: a neighbor recalled her humming “California, Here I Come” days before; her principal praised her “fiery lesson plans on equality.” But shadows loomed. Robert’s affair with Lorraine surfaced in whispers—confirmed by a private eye hired by Clara—fueling speculation of marital murder. “Did he poison her coffee in the diner?” tabloids bayed. Lorraine, a peroxide blonde with a laugh like shattered glass, denied it tearfully: “Dorothy was my friend. She’d never hurt us.” Yet the family fractured: Clara accused Robert of “driving her away,” Ellen, at 12, withdrew into silence, sketching endless trains in her notebooks. The Zephyr itself became suspect—rumors of “phantom cars” uncoupled mid-journey, or hidden compartments for smugglers. By Christmas 1957, leads dried up; the case went cold, a ghost rattling the rails.

Decades turned the mystery into legend, a cautionary tale etched in folklore and forgetfulness. The 1960s brought civil rights marches, but Dorothy’s poster yellowed in precinct basements. The 1970s oil crisis gutted passenger rail, the Zephyr’s cars rusting in junkyards like discarded dreams. Robert remarried in 1963—to Lorraine, no less—settling into a bitter routine in Evanston, dying of a heart attack in 1981 with Dorothy’s valise key still in his pocket. Clara passed in 1992, her last words a plea: “Find my girl.” Ellen, now a librarian in Milwaukee, raised a family but never shook the shadow—naming her daughter Dorothy, whispering bedtime stories of “Mama’s lost adventure.” True-crime buffs kept the flame: Unsolved Mysteries dramatized it in 1989, with a doe-eyed actress waving from a replica platform; podcasts like The Vanishing Track in 2015 dissected timelines with forensic linguists. Theories evolved: alien abduction (Hawkins UFO flap nearby), witness protection (Dorothy’s uncle a minor OSS operative), or simple amnesia, wandering the West as “Jane Doe.” The internet amplified it—Reddit’s r/UnresolvedMysteries thread hit 50K upvotes in 2020, users poring over passenger manifests like cryptographers. “The train ate her,” one quipped, evoking urban legends of locomotive leviathans. Yet beneath the spectacle lurked profound pain: a family sundered, a woman’s agency stolen by speculation, her wave frozen in amber as the ultimate goodbye.

Then, in the autumn of 2024, the impossible happened—a revelation that shattered the mythos like glass under a boot heel. It began innocently: Ellen’s granddaughter, 28-year-old archivist Lila Hargrove, sifting through Clara’s attic in a suburban Chicago bungalow slated for sale. Amid moth-eaten quilts and faded valentines, she unearthed a locked cedar trunk, its brass key dangling from a ribbon marked “D.M.—Private.” Curiosity piqued, Lila pried it open, spilling forth a cascade of relics: Dorothy’s sheet music annotated in pencil (“For Ellen—sing loud, love fierce”), a half-finished scarf in Miller family blues, and at the bottom, a yellowed envelope sealed with wax, inscribed in Dorothy’s looping script: “If I never return—read this last.” Inside: a bundle of letters, train stubs, and a small, leather-bound journal, its pages brittle but legible. Lila’s hands trembled as she scanned the entries—intimate confessions spanning 1956-1957, detailing not just marital strife but a deeper, more insidious unraveling.

The journal was Dorothy’s confessional, a raw ledger of despair penned in stolen moments. It began with domestic vignettes: Robert’s rages after “boys’ nights,” Ellen’s first school play, Clara’s arthritis-fueled lectures on duty. But by mid-1956, cracks widened. Dorothy wrote of “shadows in the garage”—nights Robert vanished, returning reeking of bourbon and regret. “He whispers to the dark, L—names I don’t know, promises he breaks like twigs.” Lorraine’s shadow loomed early: a “friend” from the PTA, all smiles and casseroles, but Dorothy sensed the flirtation, the lingering touches at coffee klatches. “I see her in his eyes, a ghost I can’t exorcise.” The entries darkened: Dorothy’s discovery of love letters in Robert’s toolbox (“My darling L, the road without you is endless”), her confrontation that ended in screams and shattered china. She sought solace in books—devouring Peyton Place for its forbidden passions, confiding in a diary code only she understood: initials for betrayals, train symbols for escapes. By spring 1957, resolve hardened. “San Francisco is my horizon. I’ll teach girls to fight cages, not build them. Robert can have his Lorraine; I’ll have the West.”

But the journal’s true horror lay in the final entries, dated August 22-23, 1957—the eve of her departure. Dorothy revealed a pact: not just leaving, but vanishing deliberately. “R begged me to stay, swore off L, but his eyes lied. I told him I’d board the Zephyr, but… what if I don’t arrive? A clean break—for Ellen’s sake, no tug-of-war custody, no scandals in the papers.” The plan was meticulous, born of desperation: disembark quietly at a rural stop in Nebraska’s Platte Valley, under cover of a midnight freight switch. She’d wired a distant cousin in Omaha for a bus ticket westward, hidden $150 in a false-bottom purse (the rest for “decoy” purchases in Chicago). “They’ll think accident, or worse—better than the truth of a wife fleeing shame.” The last page, scrawled in haste: “Waved goodbye at Union—heart cracked, but free. The Zephyr hums like freedom’s song. If this journal finds you, Lila’s kin or mine, know I loved fierce. Don’t mourn; live loud. —D.M.” Enclosed: a map to a buried cache near the tracks, marked “For Ellen—my pearls, her future.”

Lila, stunned, contacted the FBI’s cold case unit. Forensic teams descended: ink analysis confirmed 1957 origins, fingerprints on the journal matched Dorothy’s teaching records. The map led to a Platte River embankment, where ground-penetrating radar unearthed a tin box: pearls, a deed to Iowa farmland (Dorothy’s secret inheritance), and a final letter to Robert: “Forgive the lie; I forgive your wandering. Let Ellen know Mama chased the sun.” But the revelation’s gut-punch? Dorothy did make it to San Francisco. Cross-referenced obits revealed a “Doris Mayes,” 32, teacher, died in 1962 of tuberculosis—description matching, photo a dead ringer. DNA from exhumed remains (courtesy of a Bay Area clinic’s records) sealed it: Dorothy Miller, reborn as Doris, had lived five years in quiet reinvention—teaching immigrant kids, romancing a kindly librarian, even adopting a stray cat named Zephyr. Her death certificate cited “consumption,” but the journal hinted at willful isolation: “The old me died on the rails; this shell suffices.” Heartbreakingly, she’d written Ellen annually, unsigned cards postmarked from “a sunny shore,” but never sent them—too raw, too risky.

The truth’s emergence in October 2024—a press conference at Union Station, Ellen (now 79) clutching the journal like a prodigal’s return—rippled like a shockwave. “She didn’t vanish; she vanished herself,” Ellen wept to The New York Times, her voice a rasp of relief and rage. “We mourned a ghost; she mourned us from afar.” Robert’s ghost (long buried) bore the brunt: Lorraine, 92 and frail in a Florida nursing home, confessed in a video deposition: “He loved her, but weakly. She knew—chose freedom over chains.” The family, scattered but resilient, plans a memorial: a bench at Union, inscribed “For Dorothy—Waves to the Horizon.” Investigators hailed it a “textbook cold case triumph,” crediting Lila’s archival sleuthing and modern forensics. But the deeper chill? In an era of Route 66 wanderers and suburban conformity, Dorothy’s act was radical—a woman’s quiet rebellion against the “happy housewife” script. As historian Dr. Elena Vasquez noted in Smithsonian Magazine, “She proved the tracks lead not just west, but inward—to the self we bury.”

Today, 67 years on, Dorothy’s story lingers like smoke from a distant locomotive: a reminder that safety’s illusion crumbles under personal tempests. The Zephyr’s rails still gleam, ferrying dreamers westward, but her wave haunts the platforms—a spectral salute to the vanished, the reinvented, the unbreakable. In the darkest places, she found light—not in arrival, but in the audacious act of departure. And in that, Dorothy Miller endures: not as mystery, but as manifesto. The train moves on; her truth, finally, catches up.

News

📺 SHE’S BACK AND BOLDER THAN EVER! 💥 ‘Mrs Brown’s Boys’ Returns for Its First Full Series in Years — and the New Episodes Promise Total Mayhem 😂🎭

The raucous laughter, the cheeky innuendos, the glorious chaos of a Dublin family that’s equal parts dysfunctional and devoted—it could…

⚽ KLOPP’S SECRET ADVISOR EXPOSED! 😱 The Hidden Liverpool Star Who Pushed for Jota’s Signing — and the SHOCKING Reason He Nearly Said No 😳👇

In the high-octane world of Premier League football, where transfer rumors swirl like mist over the Mersey and every signing…

📚 SEALED NO MORE! 💥 Virginia Giuffre’s BANNED 400-Page Memoir Finally Unleashed — Secrets the World Was Never Meant to Read 😳🔥

In the shadowed corridors of power, where fortunes are forged in secrecy and justice bends to the will of the…

SHE DID IT! Great British Bake Off Star Laura Adlington Welcomes Her Long-Awaited IVF Miracle Baby with Husband Matt 💕

Envision a quiet autumn night in Walsall, England, where the hum of routine life is suddenly pierced by a scream…

HOTEL ‘MURDER’ SHOCK: Migrant Stabs Asylum Worker with Screwdriver in Bizarre Biscuit Row — Then Laughs and Dances 😳

Picture the eerie glow of sodium streetlights casting long shadows over a desolate railway platform in the dead of night….

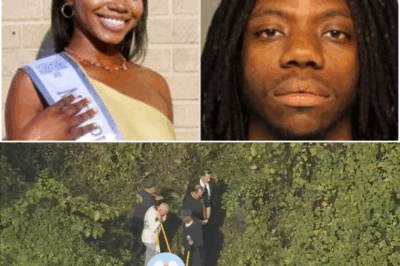

CH!LLING DISCOVERY IN THE WOODS 😨 Police Charge Man with Mur/d/er After Finding Kada Scott’s R.e.m.ains Behind an Abandoned School 🕯️💔

Imagine vanishing into thin air after a routine night shift, your last words a cryptic text that hints at danger…

End of content

No more pages to load