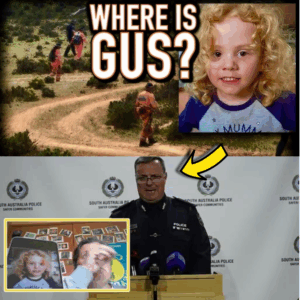

In the vast, unforgiving expanse of South Australia’s outback, where the red dirt stretches endlessly under a merciless sun and the nights swallow everything in inky blackness, a four-year-old boy’s laughter fell silent on September 27, 2025. Augustus “Gus” Lamont, a cherubic toddler with tousled blond hair and an infectious grin that could melt the hardest heart, was last seen frolicking on a simple mound of dirt just outside his family’s remote homestead at Oak Park. It was around 5 p.m.—a golden hour in the harsh landscape 40 kilometers south of the dusty speck of a town called Yunta, some 300 kilometers north of Adelaide. His grandmother, Shannon Murray, had glanced out the window moments earlier, watching him play with the unbridled joy only a child can muster in such isolation. Thirty minutes later, at 5:30 p.m., she stepped outside to call him in for dinner. The yard was empty. Gus was gone.

What followed was a frantic half-hour scramble that would soon balloon into one of the largest search operations in Australian history—a desperate bid to pierce the veil of the outback’s secrets. But thirteen days later, as the clock ticks past midnight on October 10, the official narrative peddled by Gus’s family is crumbling under its own weight. Whispers of inconsistencies, family feuds, and a timeline that defies logic have police quietly shifting their gaze from the endless scrubland to the very homestead walls that once echoed with the boy’s giggles. The outback may be vast, but how far could a tired, hungry four-year-old really go in just thirty minutes? And why, in the fading light of dusk, did no one hear his cries?

The Oak Park property is no suburban backyard—it’s a sheep station carved out of the Flinders Ranges’ rugged fringes, where the nearest neighbor might be kilometers away, and the air hums with the low buzz of flies and the distant bleat of livestock. The family—mother Jess Lamont, grandmother Shannon Murray, and grandparent Josie Murray—lived a life of quiet seclusion here, tending to the land with a rhythm dictated by the seasons. Jess, in her early thirties, had uprooted her life to raise Gus and his one-year-old brother, Ronnie, in this isolated haven. Josie, a transgender woman whose presence has stirred more than a few local tongues, shared the load, her bond with the boys reportedly as fierce as the outback winds. Father Joshua Lamont, however, was a ghost in this equation, residing 100 kilometers away in a separate home after years of escalating tensions with Josie. Court documents from custody disputes paint a picture of a fractured unit: accusations of unsafe conditions, heated arguments over parenting, and a restraining order that kept Joshua at arm’s length. He wasn’t even on the property that fateful Saturday; police notified him hours after the alarm was raised, when the sun had long dipped below the horizon.

The family’s initial account was textbook parental panic: Gus, clad in a blue shirt and shorts, had wandered off while they were momentarily distracted inside the modest weatherboard house. They searched the property for three full hours—scouring the dirt mound, the shearing sheds, the dry creek beds snaking through the 10,000-acre station—before dialing triple zero at around 8:30 p.m. By then, darkness had fallen like a shroud, the temperature plummeting from the day’s 28-degree scorch to a bone-chilling 10 degrees. Rescue crews arrived swiftly: South Australian Police, State Emergency Service volunteers, Aboriginal trackers with an intimate knowledge of the land’s hidden folds, and even 48 members of the Australian Defence Force, their helicopters thumping overhead with infrared scanners slicing through the night.

For ten grueling days, the outback became a hive of activity. Trail bikes zipped across the gibber plains, drones buzzed like mechanical hornets mapping every square meter, and ground teams combed the spinifex grass for the slightest sign—a scuff in the dust, a discarded toy, the glint of a small shoe. Experts marveled at the scale: SES veteran Jason O’Connell called it “baffling,” noting the flat, open terrain should have yielded clues aplenty. A single footprint, etched 500 meters from the homestead, sparked brief hope—small enough for a child’s sole, pointing vaguely toward a distant fence line. But trackers dismissed it almost immediately; isolated prints like that don’t appear in isolation. No hat, no clothing fibers, no echoes of distress on the evening breeze. Not even the opportunistic wedge-tailed eagles, ever-vigilant scavengers of the outback, circled suspiciously overhead.

By October 7, the official word came down: the search was scaled back. Assistant Police Commissioner Ian Parrott, his voice heavy with the weight of futility, announced that medical experts had advised little chance of survival after such exposure. The operation shifted from rescue to recovery, with the case handed to the Missing Persons Investigation Section. The helicopters fell silent, the ADF packed up their tents, and the homestead reverted to an eerie quietude, save for the wind rattling the tin roof. Josie Murray, speaking through gritted teeth to a lone reporter, summed up the family’s resolve: “We’re still looking for him.” But beneath that steely facade, cracks were forming.

It starts with the timeline, that razor-thin thirty-minute window that’s become the linchpin of skepticism. In a place like Oak Park, where the horizon mocks any notion of escape, how does a four-year-old boy—barely knee-high to an adult, with legs no longer than a kangaroo joey’s—vanish without a trace? Gus wasn’t some wiry outback urchin hardened by the land; photos show a soft-featured child more at home with picture books than perilous treks. Preschoolers tire quickly; they’d curl up in a hollow log or wail for mummy within minutes, their voices carrying for hundreds of meters in the still air. Yet the family claims no shouts pierced the gloaming, no tiny form stumbled back toward the lights flickering in the homestead windows. And then there’s the encroaching night: by 7 p.m., full dark had claimed the sky, stars pricking through like indifferent witnesses. A lost child doesn’t press on into that abyss; hunger gnaws, fear paralyzes, and exhaustion wins. Experts in child psychology and survival whisper the same: survival odds plummet after sunset in sub-zero chills. Statistically, 90 percent of missing kids under five are found within the first hour—usually by family, right under their noses.

But the discrepancies don’t stop at distance and dusk. Why the three-hour delay in calling authorities? In a remote station with spotty phone coverage, sure, but a satellite phone or HF radio is standard issue for such properties—lifelines against the isolation. The family insists they combed every inch first, hearts pounding with dread. Yet in those initial hours, as shadows lengthened, no one thought to alert Joshua? He learned of it from police, not a frantic voicemail, arriving the next morning to a scene already buzzing with outsiders. And the family dynamics—oh, those simmering resentments—add fuel to the fire. Joshua’s estrangement from Josie wasn’t amicable; it stemmed from explosive rows over Gus’s safety, with him alleging the property’s isolation posed risks to the boys. Custody battles loomed, paperwork strewn across kitchen tables like unspoken indictments. Locals in Yunta, a tight-knit community of 100 souls, have fielded whispers: the Murrays as “gentle but guarded,” their transgender grandparent a lightning rod for gossip in conservative rural circles. Online forums buzz with conspiracy: Was Gus’s disappearance a ploy in the custody war? Did family secrets—buried arguments, perhaps a moment of unchecked anger—boil over in that fatal half-hour?

Police aren’t saying much, but actions speak volumes. The Missing Persons Unit’s involvement signals a pivot: from aerial sweeps to forensic deep dives. They’ve combed the homestead for digital footprints—phones, security cams (if any), even the family’s battered Land Rover for traces of soil displacement. Interviews have stretched into the wee hours, polygraphs floated like trial balloons. A source close to the investigation (speaking off-record, naturally) hints at “inconsistencies in statements” that don’t align with the physical evidence—or lack thereof. That single footprint? Under scrutiny now, its origins probed with the zeal of a detective unraveling a locked-room mystery. And the family’s pleas for privacy—barring well-meaning volunteers from the gate—reek of deflection to some. Neighbor Alex Thomas, a weathered Yunta farmer, has begged the public to back off, decrying “online vitriol” that paints the family as villains. “They’re hurting beyond belief,” he says. But in the court of public opinion, doubt festers.

Thirteen days. That’s an eternity in a missing child case, each sunrise a stab to the collective heart. Gus Lamont, with his gap-toothed smile frozen in family snapshots, haunts the national psyche—a symbol of innocence snatched by the unknown. Was it a dingo’s opportunistic lunge, as some early theories suggested? A flash flood in a hidden gully? Or something far more human, born of love turned toxic in the pressure cooker of isolation? The outback has claimed many souls, from lost explorers to wayward stockmen, but Gus’s story tugs at something primal: the fragility of trust in those we hold dearest.

As police peel back the layers of this rural enigma, one truth glares undeniable: the family’s story, once a beacon of shared grief, now frays at the edges. If Gus is out there—curled in some merciful nook, waiting for rescue—the clock ticks mercilessly. But if the answers lie closer to home, in the shadows of unspoken feuds and half-remembered shouts, then justice demands they surface. For little Gus, the boy who vanished in thirty impossible minutes, the outback’s silence is deafening. And it’s time someone started talking.

News

Hidden Photos, Faked DNA, and a Mattress Secret: How Julia Wandelt’s Madeleine McCann Scam Unraveled.

A Polish woman named Julia Wandelt, also known under aliases like Julia Wendell and Julia Faustyna, became a global sensation…

Otamendi’s Trophy Tattoos Leave Vini Jr. in Stitches.

During a tense Champions League knockout playoff match between Real Madrid and Benfica, an unexpected on-pitch exchange between two South…

DNA From Glove Could Crack the Masked Abduction of Savannah Guthrie’s Mother.

The disappearance of Nancy Guthrie, the 84-year-old mother of NBC’s Today co-anchor Savannah Guthrie, has gripped the nation since she…

Sheriff Admits Investigation “Shambolic” — But Reveals Smoking-Gun Evidence That Could Solve Nancy Guthrie Case.

Pima County Sheriff Chris Nanos held an emotional and unusually candid press conference on February 18, 2026, where he publicly…

Harry Returns His Prince Title After Charles’s Shocking Decision—What Did the King Do?

Prince Harry has formally renounced his royal title of “Prince” and the style “His Royal Highness,” in what palace insiders…

Zack’s House Is Where the Gloves Were Found—A Facial Feature Just “Named” Nancy Guthrie’s Kidnapper.

Explosive online claims have emerged alleging that Zack—the registered owner of the silver Range Rover seized during a February 13,…

End of content

No more pages to load