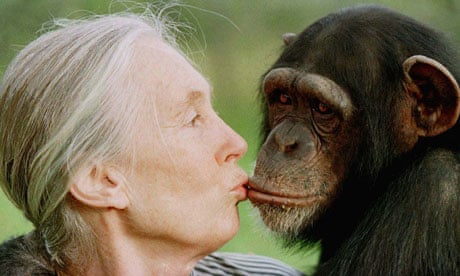

In a poignant end to a life dedicated to bridging the gap between humans and the animal world, the cause of Jane Goodall’s death has been revealed as cardiac arrest. The legendary primatologist, ethologist, and conservationist passed away peacefully in her sleep on October 1, 2025, at the age of 91, while on a speaking tour in Los Angeles, California. According to a report from TMZ, citing her official death certificate, Goodall succumbed to cardiopulmonary arrest—a sudden cessation of heart and lung function—marking a quiet departure for a woman whose voice had echoed across continents in defense of the planet’s most vulnerable inhabitants. This revelation comes weeks after her death sent shockwaves through the scientific community, environmental activists, and admirers worldwide, prompting an outpouring of tributes that celebrated her as a trailblazer who redefined our understanding of chimpanzees and humanity’s place in nature.

Goodall’s final days were emblematic of her tireless spirit. She had been traversing the United States on a demanding speaking tour, advocating for climate action and wildlife conservation with the same fervor that defined her six-decade career. Just hours before her passing, she was immersed in work, typing away on a document until 10:30 p.m., as shared by her longtime personal assistant, Mary Lewis. Scheduled to speak at UCLA on October 3 and participate in a tree-planting ceremony in Pasadena on the day her death was announced, Goodall’s itinerary reflected her unyielding commitment to inspiring change. Her last public appearances during New York Climate Week from September 21-28 saw her urging audiences to confront the climate crisis head-on, declaring it “the greatest challenge of our time” and emphasizing that “every day that we live, we make an impact on the planet.” Tragically, she was found lifeless the next morning at a friend’s home, a serene exit that contrasted with the dynamic life she led.

Jane Goodall during one of her recent speaking engagements, captivating audiences with her message of hope and action.

Born Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall on April 3, 1934, in Hampstead, London, to Mortimer Herbert Morris-Goodall, a businessman, and Margaret Myfanwe Joseph, a novelist known as Vanne Morris-Goodall, young Jane’s fascination with animals began early. The family relocated to Bournemouth, where she attended Uplands School in Poole. A pivotal moment came when her father gifted her a stuffed chimpanzee named Jubilee instead of a traditional teddy bear, igniting a lifelong passion for primates and Africa. As a child, she dreamed of living among wild animals, a vision that would propel her from secretarial work to groundbreaking scientific discovery.

Without a formal university degree initially, Goodall’s entry into the world of primatology was unconventional and inspiring. In 1957, she ventured to Kenya, where she secured a position as secretary to paleontologist Louis Leakey. Impressed by her enthusiasm, Leakey sent her to study primate behavior in London and, in 1960, funded her expedition to Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania. Accompanied by her mother for safety amid local unrest, Goodall became the first of Leakey’s “Trimates”—a trio of women researchers including Dian Fossey (gorillas) and Birutė Galdikas (orangutans)—tasked with studying great apes in their natural habitats.

Her early days at Gombe were marked by patience and perseverance. For months, the chimpanzees fled at her approach, but Goodall’s gentle persistence paid off. She named them—David Greybeard, Goliath, Flo, and others—rather than assigning numbers, a method criticized as anthropomorphic but which allowed her to document their individual personalities and social dynamics intimately. This humanizing approach revolutionized ethology, challenging the scientific establishment’s detachment.

A young Jane Goodall interacting with a chimpanzee in Gombe, capturing the bond that defined her research.

Goodall’s key discoveries shattered long-held beliefs about what separates humans from animals. In 1960, she observed chimpanzees modifying twigs to “fish” for termites, proving they used tools—a trait previously thought unique to humans. Leakey’s famous response: “We must now redefine man, redefine tool, or accept chimpanzees as human!” She documented their hunting behaviors, revealing coordinated group hunts for smaller primates like colobus monkeys, and their capacity for warfare, as seen in the brutal 1974-1978 Gombe Chimpanzee War between splintered communities. Goodall also uncovered darker aspects, such as infanticide and cannibalism among dominant females, balancing her initial view of chimpanzees as “nicer than human beings” with their complex, sometimes violent nature.

These findings were detailed in her 1965 PhD thesis from the University of Cambridge, where Leakey had arranged for her to study without a bachelor’s degree—a rare exception. Her work gained global attention through National Geographic articles and her bestselling book, In the Shadow of Man (1971), translated into 48 languages. By the 1970s, Goodall had transitioned from researcher to advocate, founding the Jane Goodall Institute (JGI) in 1977 to support Gombe’s ongoing studies and promote conservation worldwide.

The JGI expanded into 19 offices, launching initiatives like the Tchimpounga Chimpanzee Rehabilitation Centre in the Republic of the Congo (1992), housing over 100 orphaned chimps, and the Lake Tanganyika Catchment Reforestation and Education (TACARE) project (1994), which combated deforestation while providing community education and health services. In 1991, Goodall started Roots & Shoots, a youth empowerment program that grew to over 10,000 groups in more than 100 countries, encouraging young people to tackle environmental, animal, and humanitarian issues.

Her activism extended beyond chimpanzees. A vegetarian turned vegan by 2021, Goodall campaigned against factory farming, animal testing, and habitat destruction. She collaborated with NASA on satellite imagery to monitor deforestation, cofounded Ethologists for the Ethical Treatment of Animals in 2000, and petitioned for endangered status for all chimpanzees (achieved in 2015). As a United Nations Messenger of Peace since 2002, she addressed climate change, urging plant-based diets and ecocide laws. In her later years, she traveled 300 days annually, authoring 32 books and inspiring documentaries.

Goodall sharing a tender moment with a chimpanzee, symbolizing her lifelong advocacy for animal rights.

Goodall’s accolades were as numerous as her contributions. Appointed Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) in 2003, she received the French Legion of Honour, the Kyoto Prize, the Templeton Prize (2021), and the U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Joe Biden in January 2025. Time magazine named her one of the 100 most influential people in 2019, and she was honored with honorary doctorates and fellowships from institutions like Cambridge and the Open University of Tanzania.

On a personal level, Goodall married twice: first to wildlife photographer Hugo van Lawick in 1964, with whom she had son Hugo (born 1967), divorcing in 1974; then to Tanzanian parliamentarian Derek Bryceson in 1975, who died of cancer in 1980. She lived with prosopagnosia, a face-recognition disorder, and resided in Bournemouth, England. Raised Christian, she experienced a mystical moment in 1977 that deepened her belief in a “guiding power,” harmonizing faith with evolution. Surprisingly, she expressed openness to undiscovered species like Bigfoot.

In her final months, Goodall remained active, though Lewis noted she felt “finite.” Friend Patrick McCollum recalled planning a drink in Los Angeles, only for her to pass the night before, after voicing concerns it might be their last. Her death certificate confirmed cardiac arrest, a common cause in the elderly, often linked to underlying heart conditions but occurring suddenly without warning.

The world responded with profound grief and admiration. Prince Harry and Meghan, Duchess of Sussex, hailed her “remarkable ability to inspire.” Former U.S. Vice President Al Gore praised her environmental leadership, while Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau called her an “extraordinary legacy.” Leonardo DiCaprio, Ellen DeGeneres, and UN Secretary-General António Guterres joined the chorus, emphasizing her impact on conservation.

On X (formerly Twitter), tributes flooded in. User @mindfulheal lamented the loss alongside Robert Redford and Diane Keaton, noting their purposeful lives. @teachergoals shared a simple “R.I.P. Jane Goodall” with an orange heart. @NewsWire_US highlighted her whimsical final wish: to blast Trump, Musk, and Putin into space. Organizations like Best Friends Animal Society quoted her: “What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.” Videos circulated, including a rescued chimp hugging her and messages urging youth empowerment.

The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) mourned while celebrating her achievements. The Sierra Club reflected on her as “one of us,” embodying environmentalism. Green Matters compiled tributes, underscoring global mourning. Even in death, Goodall inspired, with Netflix releasing Famous Last Words featuring her interview.

An iconic image of Goodall reaching out to a young chimpanzee, illustrating the profound connections she fostered.

Goodall’s legacy is immeasurable. She humanized animals, proving chimpanzees possess emotions, tools, and societies akin to ours, fostering empathy that fueled conservation efforts. Through JGI and Roots & Shoots, she empowered generations to act. As McCollum revealed, some of her ashes will be kept in the World Peace Violin, symbolizing her harmonious vision. Survived by her son Hugo and three grandchildren, Goodall leaves a world forever changed by her curiosity, compassion, and courage.

In her own words, from a final message: “Together we can change the world.” As tributes continue, her call resonates—urging us to honor her by protecting the planet she so fiercely loved. Jane Goodall didn’t just study chimpanzees; she taught us to see ourselves in them, and in doing so, to be better stewards of Earth.

News

She Walked Out of a Quiet Indiana Suburb at 10 PM — 15 Days Later, a 17-Year-Old Girl Is Still Missing and Police Say She May Be in Danger 🚨💔

The quiet streets of Fishers, Indiana, usually hum with the predictable rhythm of suburban life—school buses rolling by, neighbors exchanging…

💔📱 “She Did Not Act Alone”: Father Rejects Runaway Theory as Teen Daughter Vanishes Without a Trace

A quiet suburban night shattered by the inexplicable. The streetlights flicker softly over manicured lawns, families tuck into bed after…

🚓💸 Cruel Twist in NASCAR Tragedy: Greg Biffle’s Home Burglarized, $30,000 Cash Taken Less Than a Month After Deadly Plane Crash

arrow_forward_ios Watch More Pause 00:00 00:08 01:38 Mute Powered by GliaStudios Discover more Online movie streaming services On December 18,…

😨🚓 Police Said Suicide — Then a Masked Ex Arrived with Evidence: a Black Bag at the Police Station — Police Reopened the Death of Texas Teen Camila Mendoza

In the sun-baked sprawl of El Paso, Texas, where the Rio Grande whispers secrets across the border and holiday lights…

💔🌟 Australia Mourns in Shock: Why Rachael Carpani’s Family Kept Her Death Secret for 14 Days — And What They Were Protecting

The world of Australian television lost a shining star on December 7, 2025, but for nearly two weeks, no one…

‘I’ve Never Seen Her Like This’ 😢🏥: AFL Legend Stephen Silvagni Speaks Through Tears as Jo Silvagni Is Rushed to Hospital

Under the harsh fluorescent lights of a private Melbourne hospital entrance, the man once feared as one of the AFL’s…

End of content

No more pages to load