When Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson released “Luckenbach, Texas (Back to the Basics of Love)” in April 1977, it wasn’t just a song—it was a cultural reset. Written by Bobby Emmons and Chips Moman, the track crystallized a longing for simplicity in a world increasingly tangled by commercialism and chaos. Rising to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart and crossing over to No. 25 on the Hot 100, it became an anthem for those yearning to strip life down to its essentials: love, connection, and a place to breathe. Nearly five decades later, the song’s wistful pull remains undimmed, its story rooted in a tiny Texas hamlet that symbolizes far more than its population of three.

Luckenbach, Texas, is no bustling metropolis. Nestled in the Hill Country, about 60 miles north of San Antonio, it’s a speck of a town with a general store, a post office, and a dancehall that doubles as a community pulse. Founded in 1849 by German immigrants, it was named for Albert Luckenbach, a settler whose family ran the local store. By the 1970s, it was little more than a ghost town, its cotton gin long shuttered and its population dwindled to a handful. But in 1970, an eccentric rancher named Hondo Crouch bought the town—lock, stock, and barrel—for reasons even he couldn’t fully explain. With his maverick spirit, Crouch turned Luckenbach into a haven for poets, pickers, and dreamers, hosting impromptu jam sessions under oak trees and quirky events like the “Women’s Chili Cook-Off.” It was this raw, unpolished charm that caught the ear of Nashville producer Chips Moman, who, along with Emmons, penned the song that would immortalize the town.

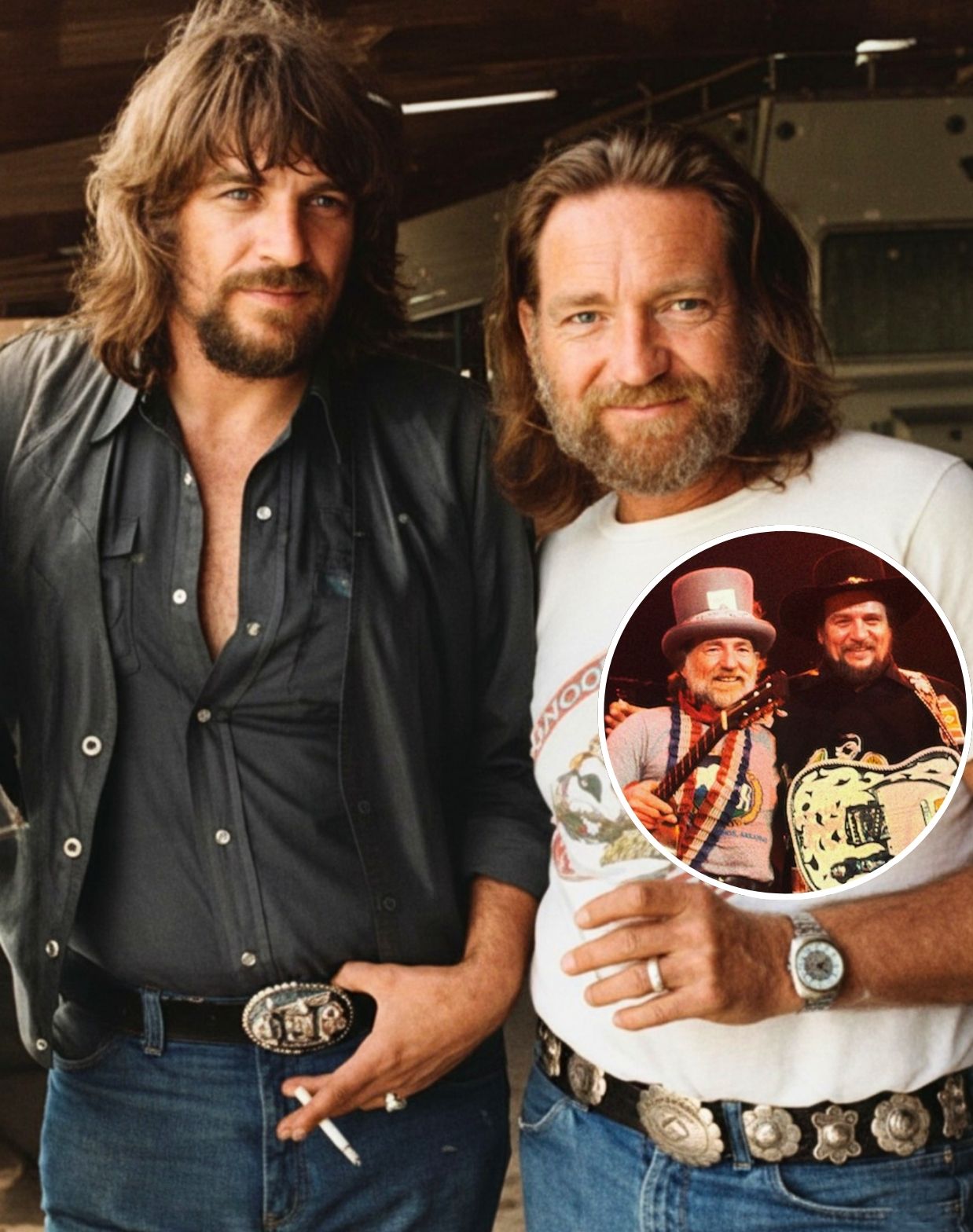

For Jennings and Nelson, both titans of the outlaw country movement, “Luckenbach, Texas” was more than a catchy tune—it was a manifesto. The 1970s were a turbulent time for both men. Jennings, the gravel-voiced Texan with a penchant for leather and rebellion, had spent years battling Nashville’s slick production machine, fighting for creative control over his music. Nelson, with his braided pigtails and restless spirit, had fled Music Row for Austin, where he forged a sound that blended country with folk, jazz, and rock. Both were weary of the industry’s demands—endless tours, media scrutiny, and the pressure to churn out formulaic hits. “We got so many gold records, we’re thinkin’ about quittin’,” Jennings growls in the song’s spoken intro, a half-joking nod to their shared exhaustion.

The song’s lyrics paint a vivid picture: two men, burdened by “four-car garages” and “high-rise penthouse shades,” dreaming of trading it all for the simplicity of a sleepy town. “Let’s go to Luckenbach, Texas, with Waylon and Willie and the boys,” the chorus beckons, evoking a place where “high-rollers” and “city life” give way to “the basics of love.” It’s a call to shed pretension, to find solace in cold beer, good friends, and a guitar’s gentle strum. The reference to “Hank Williams’ pain songs” and “Jerry Jeff’s train songs” grounds the track in country’s raw roots, while the nod to “Blue Eyes Cryin’ in the Rain”—Nelson’s own 1975 hit—adds a layer of self-awareness, as if the duo is winking at their own legend.

Recorded at American Sound Studio in Memphis, the track’s production is deceptively simple: a shuffling acoustic rhythm, a loping bassline, and Nelson’s weathered nylon-string guitar, Trigger, weaving through Jennings’ baritone like an old friend. The duet format was a natural fit—Jennings and Nelson had been collaborators since the early 1970s, their chemistry forged in late-night jam sessions and shared battles against Nashville’s constraints. Released as the lead single from Jennings’ album Ol’ Waylon, the song struck a chord with listeners who felt the same itch for authenticity. By July 1977, it topped the country charts, staying there for six weeks, and its crossover appeal drew rock and pop fans alike, cementing the outlaw movement’s mainstream breakthrough.

Luckenbach itself wasn’t prepared for the spotlight. Almost overnight, the sleepy town became a pilgrimage site. Fans flocked to the general store, snapping photos by the weathered “Luckenbach, Texas, Pop. 3” sign and scrawling messages on the dancehall walls. Hondo Crouch, dubbed the “Imagineer of Luckenbach,” leaned into the fame, hosting festivals that drew thousands. “It’s not a place you find—it finds you,” he once said, a line that became the town’s unofficial motto. After Crouch’s death in 1976, just months before the song’s release, his daughter Becky kept the flame alive, ensuring Luckenbach remained a living monument to its myth. Today, the dancehall hosts near-nightly shows, from local pickers to stars like Robert Earl Keen, while events like the annual Mud Dauber Festival keep the quirky spirit intact.

The song’s cultural impact runs deeper than tourism. It captured a universal longing for escape, resonating with anyone who’s felt trapped by modernity’s grind. For Jennings and Nelson, it was personal. Jennings, who died in 2002 at age 64, often spoke of his struggles with addiction and the toll of fame. “I’d look in the mirror some days and not know who was lookin’ back,” he wrote in his 1996 autobiography. Nelson, now 92 and still touring, has called Luckenbach “a state of mind,” a place where “you don’t need much to be happy.” Their friendship, tested by years on the road, was a cornerstone of the song’s authenticity—two men who’d lived the highs and lows, singing not just to fans but to each other.

Critics have long debated the song’s legacy. Some, like Rolling Stone’s Dave Marsh, called it a “perfect distillation of outlaw ethos,” blending grit with vulnerability. Others, like historian Bill Malone, noted its irony: a song about rejecting commercialism became a commercial juggernaut, spawning T-shirts, bumper stickers, and even a Luckenbach-themed beer. Yet its sincerity has never been in doubt. “It’s not about the town—it’s about what the town stands for,” said Austin musician Ray Wylie Hubbard, who played alongside Jennings and Nelson in the 1970s. “It’s the idea that you can step away from the noise and find something real.”

Data backs the song’s enduring pull. According to Spotify, “Luckenbach, Texas” has racked up over 100 million streams as of October 2025, a testament to its cross-generational appeal. YouTube views of the official audio and live performances exceed 50 million, with fan-uploaded covers adding millions more. The song’s influence ripples through modern country, from Chris Stapleton’s raw traditionalism to Kacey Musgraves’ introspective storytelling. Even non-country artists, like the rock band Dawes, have cited it as a touchstone for lyrical economy.

For Luckenbach itself, the song’s legacy is tangible. The town’s website reports 1.2 million visitors annually, a staggering figure for a place with one stop sign. The general store, now a gift shop, sells everything from cowboy hats to “Everybody’s Somebody in Luckenbach” magnets. The dancehall, with its tin roof and creaky floors, remains a bucket-list venue for musicians. “We don’t try to be anything we’re not,” says manager Kathy Morgan. “People come here to feel what Waylon and Willie sang about—a little peace, a little truth.”

The song’s message feels especially prescient in 2025, as urban sprawl and digital overload push people toward simpler pleasures. Social media posts on X reveal fans still quoting the lyrics—“This successful life we’re livin’ got us feudin’ like the Hatfields and McCoys”—to lament everything from political divides to smartphone addiction. One user, @TexasTwang22, wrote: “Listened to Luckenbach today and felt my soul exhale. We need that place now more than ever.” Another, @HillCountryHeart, posted a photo of the dancehall at sunset, captioned: “Where the world can’t find you.”

Jennings and Nelson never claimed to have all the answers, but “Luckenbach, Texas” offers a roadmap. It’s not about running away—it’s about running toward something better. Whether that’s a literal place or a quiet corner of the heart, the song reminds us that simplicity is its own kind of rebellion. As Nelson said in a 2023 interview, “Luckenbach ain’t just a town—it’s where you go when you’re tired of goin’.” For a world still chasing its tail, that’s a lesson worth singing about.

News

Rihanna Responds to a Fan Saying, “They Saying It’s 2016, Rih”: What Her Viral Reply Really Means

When a fan recently commented, “They saying it’s 2016, Rih,” few expected Rihanna to respond. She often ignores random online…

Rihanna’s Unmatched Face Card: How One Look Became a Cultural Phenomenon

Few celebrities command attention the way Rihanna does. Across red carpets, candid street photographs, and unfiltered social media moments, one…

400,000 FRANCS FOR RELEASE: PROSECUTORS SEEK BAIL FOR OWNERS AFTER DEADLY CRANS-MONTANA NEW YEAR FIRE

Prosecutors in Sion have requested a total of 400,000 Swiss francs in bail to grant provisional freedom to Jacques and…

📰 RCMP RELEASES NEW TIMELINE DETAILS IN LILLY AND JACK SULLIVAN CASE AS ALLEGED MESSAGES SPARK FRESH CLAIMS

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has entered another sensitive phase as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police released new…

JUST NOW: Investigators Flag Timeline Issues and Re-Examine Key Details in the Disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has taken an unexpected and unsettling turn, according to the latest update released…

A new wave of controversy erupted online this week after the daughter of an NBA legend reportedly came forward with what she described as troubling information involving Stefon Diggs and his relationship with Cardi B.

According to circulating social-media claims, she suggested that Cardi B should reconsider her involvement with the NFL star, citing alleged…

End of content

No more pages to load