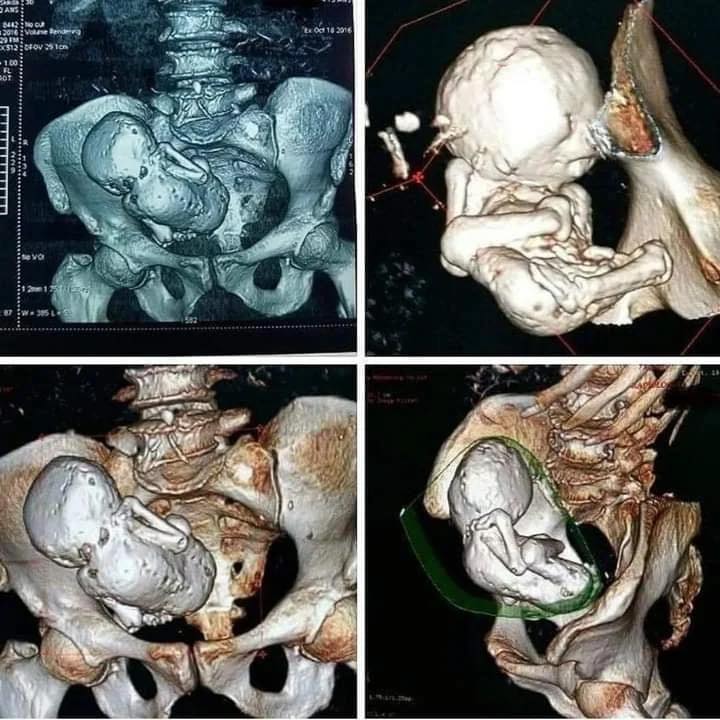

For decades, an 82-year-old woman endured vague abdominal discomfort, chalking it up to age or a stubborn “tumor” that doctors could never quite pinpoint. But when sharp pains finally drove her to a Bogotá hospital in late 2013, scans unveiled a medical mystery straight out of a nightmare: a fully formed, four-pound calcified fetus — a “stone baby” — lodged in her abdomen, preserved like a fossil for over 40 years. The rare condition, known as lithopedion, stunned the medical team and ignited global headlines, reminding the world that the human body harbors secrets capable of defying time itself.

The unnamed patient, a grandmother from rural Colombia, arrived at the clinic complaining of severe pelvic agony that had worsened over months. Initial exams suggested ovarian cysts or fibroids — common in elderly women. But an X-ray ordered for confirmation lit up like a horror film still: a skeletal form, curled in fetal position, encased in a thick calcium shell, nestled among her intestines. “It was unmistakable,” said Dr. Luis Guillermo Garcés, the lead obstetrician at the hospital. “The bones were intact, the skull clearly visible. She’d been carrying this for her entire adult life without a clue.”

Lithopedion — from the Greek “lithos” (stone) and “paidion” (child) — isn’t just a quirk of biology; it’s a survival mechanism gone surreal. It arises in ectopic pregnancies, where a fertilized egg implants outside the uterus, often in the fallopian tubes or abdominal cavity. In this woman’s case, doctors believe the fetus developed in her abdomen around age 40, sometime in the early 1970s. When it died — likely from lack of oxygen or placental failure after 12 to 14 weeks — the body couldn’t expel or absorb it. Instead, her immune system walled it off, depositing layers of calcium phosphate to neutralize the dead tissue and prevent sepsis. The result? A mummified “stone child” weighing nearly four pounds, roughly the size of a full-term newborn, that had silently shared her body for four decades.

Such cases are vanishingly rare, with fewer than 300 documented worldwide since the first recorded instance in 1582. Abdominal pregnancies occur in about 1 in 10,000 gestations, but modern ultrasounds catch most early. In Colombia’s resource-strapped rural areas during the ’70s, prenatal care was spotty at best. The woman, then in her prime childbearing years, might have dismissed mild cramps as indigestion or a missed period amid the chaos of family life. “She had several children vaginally after this,” Garcés noted. “The lithopedion didn’t interfere — it just… stayed.”

The discovery hit like a thunderbolt. The patient, initially relieved at a diagnosis, recoiled in horror upon seeing the X-ray. “She wept for the child she never knew,” a nurse told local media. Transferred to a specialist facility, she underwent successful surgery days later, with surgeons carefully extracting the calcified mass — now brittle and gray, like ancient pottery — without complications. Pathologists confirmed it was a male fetus, estimated at 38 weeks gestation when it perished. Post-op, the woman recovered swiftly, her pain vanishing as if the “tumor” had been a bad dream. Today, at 93, she’s said to be thriving in a Bogotá nursing home, though she rarely speaks of the ordeal.

This wasn’t the first lithopedion to shock the world, but its longevity etched it into medical lore. The earliest known case dates to 10th-century Spain, documented by surgeon Abulcasis in a treatise on battlefield wounds. In 1582, French physicians autopsied 68-year-old Madame Colombe Chatri, uncovering a 28-year-old stone baby in her abdomen — the oldest recorded at the time. By the 19th century, German doctor Friedrich Küchenmeister classified them into types: “lithokelyphos” (calcified sac only), “lithetecnon” (fetal skeleton), and hybrids. A 1996 review in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine tallied 290 cases, with women carrying them an average of 22 years — some up to 60. Astonishingly, many bore healthy children afterward, the stone sibling a silent passenger.

Recent cases echo the eeriness. In 2023, a 52-year-old Turkish woman discovered a lithopedion via pelvic X-ray after a minor accident — hers dated back 20 years. A 2024 study in Birth Defects Research analyzed 25 museum-preserved specimens, revealing how calcification mimics natural mummification: fetal bones ossify first, then envelop in a calcium cocoon, sometimes weighing up to nine pounds. Differential diagnoses include tumors or ovarian teratomas, but the fetal pose — knees tucked, arms crossed — is a giveaway. In low-resource settings, these “ghost pregnancies” persist; a 2025 report highlighted a Chilean woman carrying one for 50 years, uniquely inside her uterus rather than abdomen.

Medically, lithopedions pose stealthy threats. While asymptomatic for years, they can rupture, causing abscesses, bowel obstructions or infertility. Dr. Kim Garcsi, an ob-gyn at University Hospitals Case Medical Center, explained to ABC News: “The body treats it like a foreign object — calcifying to isolate the infection risk. But it’s no free ride; scans miss them without symptoms.” Treatment? Surgical removal, ideally laparoscopic, though older patients like the Colombian woman face higher anesthesia risks. Post-extraction, fertility isn’t an issue — but emotional scars linger. “It’s grief for a life unlived,” Garcsi added.

The case rippled beyond medicine, fueling tabloid frenzy and ethical debates. Colombian outlets dubbed it “El Bebé de Piedra,” with viral X-rays sparking online horror: “How does something this big hide for 40 years?” one user posted, amassing 50,000 likes. Feminists praised the woman’s resilience in an era of limited reproductive rights; critics decried lapses in rural healthcare. Globally, it spotlighted ectopic pregnancy gaps: In developing nations, 1 in 50 women face them undetected, per WHO data.

A decade on, the Bogotá lithopedion endures as a testament to biology’s bizarre ingenuity. Museums house similar relics — a 19th-century Irish specimen at the Warren Anatomical Museum, a Peruvian one from 1867 — but none rival the Colombian’s timeline. As Dr. Garcés reflected: “Her body protected her, and the baby, in the only way it knew how. It’s equal parts miracle and tragedy.”

For the woman, now in her twilight years, the stone baby is history — extracted, examined, and eulogized. But its legacy whispers: In the quiet chambers of our bodies, what other ghosts might dwell?

News

Rihanna Responds to a Fan Saying, “They Saying It’s 2016, Rih”: What Her Viral Reply Really Means

When a fan recently commented, “They saying it’s 2016, Rih,” few expected Rihanna to respond. She often ignores random online…

Rihanna’s Unmatched Face Card: How One Look Became a Cultural Phenomenon

Few celebrities command attention the way Rihanna does. Across red carpets, candid street photographs, and unfiltered social media moments, one…

400,000 FRANCS FOR RELEASE: PROSECUTORS SEEK BAIL FOR OWNERS AFTER DEADLY CRANS-MONTANA NEW YEAR FIRE

Prosecutors in Sion have requested a total of 400,000 Swiss francs in bail to grant provisional freedom to Jacques and…

📰 RCMP RELEASES NEW TIMELINE DETAILS IN LILLY AND JACK SULLIVAN CASE AS ALLEGED MESSAGES SPARK FRESH CLAIMS

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has entered another sensitive phase as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police released new…

JUST NOW: Investigators Flag Timeline Issues and Re-Examine Key Details in the Disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has taken an unexpected and unsettling turn, according to the latest update released…

A new wave of controversy erupted online this week after the daughter of an NBA legend reportedly came forward with what she described as troubling information involving Stefon Diggs and his relationship with Cardi B.

According to circulating social-media claims, she suggested that Cardi B should reconsider her involvement with the NFL star, citing alleged…

End of content

No more pages to load