As the crimson sun crests over the endless saltbush plains of South Australia’s Mid-North, a renewed sense of urgency grips the remote Oak Park Station. Today, South Australia Police (SAPOL) announced an intensification of search efforts at the property’s siding—a dusty rail hub 43 kilometers south of Yunta—fueled by a chilling new hypothesis: that four-year-old Gus Lamont may have been abducted and transported via train to another city. The theory, whispered among locals and gaining traction among investigators, suggests a stranger snatched the toddler from his family’s isolated homestead and spirited him away on the East-West freight line that rumbles through the station, evading the massive initial sweeps that covered thousands of hectares. In a landscape where isolation is both a blessing and a curse, this development has injected fresh dread into a case that has already shattered a tight-knit rural community and captivated the nation.

Gus Lamont, the cherubic boy with sun-kissed blond curls and a mischievous sparkle in his blue eyes, vanished on the evening of September 27 in what should have been the safest of sanctuaries: the backyard of his grandparents’ modest homestead at Oak Park Station, a sprawling 6,000-hectare sheep property carved from the unforgiving outback. At around 5 PM, as the day’s heat began to ebb, Gus was last seen by his grandmother, Josie Murray, frolicking in a makeshift sandpit—a humble pile of red dirt piled high behind the weatherboard house. Dressed in his favorite cobalt blue long-sleeved shirt emblazoned with a grinning yellow Minion, light gray pants, sturdy leather boots caked in dust, and a wide-brimmed gray sun hat to fend off the glare, the 18-kilogram tot embodied the unbridled joy of childhood. “He was our little adventurer,” Josie would later recall in a rare moment of candor, her voice cracking over the phone to reporters. “Always digging, always dreaming. One minute he was there, giggling; the next… gone.”

The alarm was raised just 30 minutes later when Josie called Gus in for dinner, her shouts echoing unanswered across the paddocks. What followed was pandemonium in paradise. The family—Josie, her partner, Gus’s mother Jess, and his one-year-old brother Ronnie—scoured the immediate grounds under the fading light, their flashlight beams cutting frantic swathes through the scrub. By nightfall, with panic setting in and temperatures plummeting to a bone-chilling 10°C (50°F), they dialed triple zero, unleashing a torrent of resources that transformed the sleepy station into a hive of activity. SAPOL’s response was swift and staggering: within hours, ground teams from the State Emergency Service (SES), local volunteers, and mounted police fanned out, their ATVs kicking up clouds of red dust. By dawn, the operation had swelled to over 200 personnel, one of the largest in South Australian history.

The aerial assault was equally formidable. PolAir helicopters thumped overhead, their infrared cameras scanning for heat signatures in the cooling night, while drones buzzed like mechanical hornets, mapping the terrain in pixel-perfect detail. Cadaver dogs, noses to the ground, probed for scents amid the saltbush and spinifex; specialist divers plunged into brackish dams and rainwater tanks, their torches piercing the murky depths. Indigenous trackers, drawing on ancestral knowledge of the land’s subtle whispers—the faint scuff of a boot in loamy soil, the bent blade of grass—joined the fray, their expertise a bridge between ancient lore and modern forensics. The Australian Defence Force contributed desert-hardened troops, trained to navigate the very hazards that threatened Gus: flash floods in dry gullies, venomous snakes coiled in the underbrush, and feral dingoes prowling the fringes.

For 10 relentless days, the search devoured the landscape. Teams traversed 47,000 hectares—an expanse vast enough to engulf a small town—enduring daytime highs of 28°C (82°F) that sapped strength like a desert mirage, and nights where the wind howled like a lament. Volunteers like Jason O’Connell, a former SES stalwart with 11 years under his belt, and his partner Jen clocked over 1,200 kilometers on foot and vehicle, their boots blistered and voices hoarse from endless calls of “Gus! August!” “We covered every inch, every shadow,” O’Connell recounted, his eyes hollowed by exhaustion. “Spinifex tearing at your legs, salt flats playing tricks in the heat—it breaks you, but you push on because he’s just a kid.” The Yunta community, a speck of 60 souls with a lone pub, general store, and fuel pump, rallied like a family at a wake: care packages of sandwiches and thermos coffee, candlelit vigils under star-pricked skies, and social media storms under #FindGus that racked up millions of shares.

A glimmer of promise flickered mid-search: a small footprint, etched in the ochre soil about 500 meters from the homestead near a dry creek bed. It matched Gus’s boot size, igniting a surge of adrenaline. Local tracker Aaron Stuart, whose family has read the outback’s signs for generations, hailed it as a “story in the dust.” But forensic scrutiny dashed the hope—the print belonged to an animal or an unrelated child from a prior visit. Other leads evaporated: reports of a suspicious vehicle on the Barrier Highway, a fleeting shadow caught on drone footage. By October 4, with medical experts deeming survival improbable after 48 hours without water in such terrain, SAPOL’s Deputy Commissioner Linda Williams delivered the crushing pivot: the active phase would scale back, handing the reins to the Major Crime Investigation Branch’s Missing Persons Unit for recovery and inquiry. “The likelihood of finding Gus alive is minimal,” she said, her words a knife to the nation’s gut. “But we will never stop seeking answers.”

The Lamonts retreated into a cocoon of grief, their world shrinking to the homestead’s sagging verandah. Josie Murray, a resilient transgender woman who transitioned years ago and has helmed the station through droughts and floods, emerged briefly to affirm: “We’re still looking for him.” Known locally as “tough as nails,” Josie has weathered not just the land’s caprices but familial strains. Gus’s father, Joshua Lamont—a burly ex-country singer who crooned as Billy Tea in dusty SA pubs—lives 100 kilometers west in Belalie North, near Jamestown, amid reported clashes with Josie over the kids’ safety on the remote property. “Josh worries it’s too wild out here for little ones,” a family friend shared. The couple remains together but geographically divided, with Joshua roused from sleep by police on disappearance night, his fury channeled into quiet advocacy. Jess, cradling Ronnie, has been a ghost, her pain etched in the vacant stare captured by a single leaked photo.

Yet, as despair settled, speculation festered. Online forums and pub yarns birthed conspiracy weeds: dingo attacks echoing Azaria Chamberlain’s tragedy, family cover-ups fueled by the custody tensions, even wild claims of ritual abduction. Fact-checkers swatted them down as “cruel fabrications,” but the void begged filling. Enter the Oak Park siding theory—a hypothesis born of the property’s overlooked artery: the East-West railway line that bisects the station, ferrying freight from Adelaide to Perth through ghost towns and gibber plains. Locals murmur of opportunistic snatchers—truckies or rail workers—who could spirit a child aboard a goods train, vanishing toward Broken Hill or beyond in under an hour. “It’s mad, but in this nowhere, mad makes sense,” confided Yunta publican Mick Hargreaves, nursing a schooner at dawn. “A kid that small? Easy to bundle on a flatcar, gone before anyone blinks.”

SAPOL, though officially dismissing abduction as “low probability” given the isolation—where strangers are rarer than rain—has quietly amplified efforts at the siding. Announced October 13, the resumed operation deploys an additional 50 personnel, including rail specialists from Australian Rail Track Corporation and forensic teams to scour sidetracks for traces: a discarded boot, a scrap of Minions fabric snagged on barbed wire. Ground-penetrating radar will probe ballast beds, while drones fitted with multispectral cameras hunt for anomalies under the ties. “New lines of inquiry warrant a focused look,” Assistant Commissioner Ian Parrott stated tersely, sidestepping details but confirming the siding’s centrality. “We’re treating every possibility with the gravity it deserves.” The expansion westward aligns with Joshua’s pleas, bridging toward Belalie North, but the rail angle evokes Cleo Smith’s 2021 abduction in WA—snatched from a campsite, rescued after 18 days—offering a sliver of precedent.

Experts weigh in with measured alarm. Criminologist Xanthe Mallett, who consulted on high-profile child cases, told ABC Radio: “The lack of evidence on the property screams third-party involvement. Remote doesn’t mean immune—opportunists prowl highways and rails.” Former homicide detective Gary Jubelin, scarred by the William Tyrrell saga, echoed: “Wander off? Possible. But zero traces after exhaustive sweeps? That’s intervention—human or otherwise.” Wildlife lurks too: dingo packs, emboldened by drought, could drag a child miles, their lairs hidden in mallee thickets.

Yunta, the linchpin town, throbs with resolve. Fleur Tiver, 66, whose ancestors grazed alongside the Lamonts since the 1800s, decries the vitriol: “They’re kind folk, not culprits. This speculation piles pain on pain.” Alex Thomas, a shearer at the pub, lectures theorists: “Out here, life’s raw—kids roam, but vanishings? Rare as hen’s teeth.” Vigils swell, pink ribbons (Gus’s favorite color) fluttering from fence posts.

As crews converge at the siding today—boots crunching gravel, detectors humming—the Lamonts watch from afar. Joshua, voice gravelly: “If he’s on a train, God help the one who took him.” Jess: “Bring my boy home.” In this theater of dust and determination, the siding holds secrets: a child’s footprint in the ballast, or just echoes of passing freights. For Gus, the Minion-clad explorer lost to the horizon, the rails may lead to answers—or an abyss. Australia listens, hearts heavy, hoping the outback yields its stolen son.

News

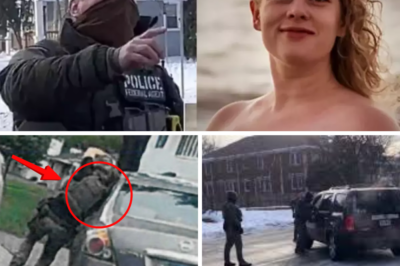

ICE Agent Involved in Fatal Shooting of Renee Good Previously Dragged 300 Feet by Vehicle in Bloomington Incident

Minneapolis, Minnesota – January 20, 2026 — The U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agent who fatally shot 37-year-old Renee…

Renee Good’s Family Refuses to Back Down: They’ve Quietly Retained One of America’s Top Attorneys — and Are Now Preparing to Release the Final Audio Recording That Could Change Everything

The family of Renee Nicole Good, the 37-year-old Minneapolis mother fatally shot by a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)…

Zion Foster Breaks Social Media Silence with Heartwarming Video of Daughter Story Amid Reports of Split from Jesy Nelson

London, January 20, 2026 — In his first public post since reports emerged of his separation from Jesy Nelson, musician…

Jesy Nelson Confirms Split from Fiancé Zion Foster Amid Heartbreaking Reality of Twins’ SMA Diagnosis

In a development that has left fans reeling, former Little Mix singer Jesy Nelson has confirmed the end of her…

A Teacher Everyone Trusted — Then She Vanished: The Tragic Case of Linda Brown and Lingering Questions After Her Lake Michigan Death

In the tight-knit Bridgeport community of Chicago, Linda Brown was more than just a special education teacher at Robert Healy…

Ex-Husband in Ohio Dentist Murders Allegedly Used Fake Details to ‘Disguise’ Himself Before Killings, Expert Says

Columbus, Ohio – January 20, 2026 — New revelations in the high-profile double murder case involving an Ohio dentist and…

End of content

No more pages to load