The courtroom in Dearborn County fell into a stunned hush as Judge Sally McLaughlin slammed the gavel, sealing the fate of Raeleigh Phillips-Steelsmith with a six-year prison sentence for reckless homicide. At 24 years old, the young mother stood before the bench, her face a mask of inscrutability—eyes downcast, lips pressed into a thin line, showing what prosecutors described as “little to no emotion” in the face of unimaginable loss. It was October 8, 2025, a crisp autumn day in southeastern Indiana, but inside the wood-paneled chamber, the air hung heavy with the weight of a nine-day-old life extinguished in the most preventable way: positional asphyxia after being left strapped in a car seat for nearly 14 hours. Emmett Phillips, the tiny victim whose name means “truth” in Hebrew, had suffocated in silence while his mother binge-watched television, oblivious or indifferent to his cries for relief.

Phillips-Steelsmith’s lack of visible remorse became the trial’s haunting refrain. As the judge recounted the facts—how the infant’s airways collapsed under his own slumped weight, his tiny body starved of oxygen and nourishment—spectators craned forward, searching her expression for a flicker of grief. There was none. “She seemed detached, almost robotic,” one courtroom observer whispered to reporters afterward. “Like she was watching someone else’s story unfold.” Prosecutor Lynn Deddens, her voice steady but edged with fury, had hammered this point in closing arguments: “This defendant betrayed the most primal bond—a mother’s instinct to protect. And now, as we mourn Emmett, she offers nothing but silence.” The sentencing capped a saga that gripped the small town of Lawrenceburg, a riverside community of 14,000 along the Ohio border, where the horrors of neglect played out in the most ordinary of settings: a modest apartment off Mary Street.

The tragedy unfolded on March 2, 2024, a Saturday that dawned unremarkable in Aurora, a neighboring village known for its historic downtown and quiet family life. Phillips-Steelsmith, then 22, had spent the previous evening at a friend’s house, a casual gathering fueled by laughter and perhaps a few drinks—details that would later fuel debates about her state of mind. With nine-day-old Emmett in tow, she buckled him into his Graco car seat around 1 p.m., the infant swaddled in a soft blue onesie, his cherubic face framed by wisps of downy hair. They made a quick stop at the Kroger supermarket in Aurora East, where surveillance footage would later capture her pushing a cart with formula and diapers, Emmett’s seat perched in the basket like an afterthought. By 2 p.m., they were back in Lawrenceburg, pulling into the parking lot of her ground-floor apartment in a weathered brick complex that housed young families and retirees alike.

What happened next defied comprehension. Phillips-Steelsmith later told investigators she noticed Emmett “seemed content” and “still asleep” upon arrival. Rather than rousing him for a feed and cuddle—standard practice for a newborn still adjusting to the world—she carried the car seat inside, plopping it on the living room floor beside the couch. The apartment, a two-bedroom rental she shared sporadically with Emmett’s father, Josh Steelsmith, was cluttered with the detritus of new parenthood: unwashed bottles on the coffee table, a bassinet shoved in the corner, stacks of onesies waiting to be folded. She flicked on the TV, sinking into an episode of The Real Housewives of Atlanta, the drama of feuding socialites a stark counterpoint to the life ebbing away at her feet.

Hours stretched into a void. Emmett, weighing just seven pounds at birth, had no way to cry out effectively. Strapped in the semi-upright position designed for short car trips, his head lolled forward, chin pressing against his chest, blocking his fragile airways. Positional asphyxia, as medical experts would explain, is a silent killer for infants: their developing neck muscles fail to support the head, compressing the windpipe without the dramatic signs of struggle that might alert a caregiver. The American Academy of Pediatrics warns against leaving babies in car seats for more than two hours outside of vehicles, citing risks of oxygen deprivation and sudden infant death syndrome. Emmett endured 13 hours and 50 minutes—14 hours without a single bottle, his body cooling from 98.6 degrees to room temperature as dehydration set in.

It wasn’t until the next morning, around 4 a.m. on March 3, that Phillips-Steelsmith stirred. Groggy from a night of fitful sleep on the couch, she glanced at the car seat. Emmett was slouched unnaturally, his skin mottled blue, limbs limp like a forgotten doll. Panic finally pierced her haze. She screamed for help, dialing 911 as friends—summoned by her frantic texts—rushed over. One, a neighbor named Tara Jenkins, performed CPR, her hands trembling as she pumped the infant’s chest on the threadbare carpet. “He was ice cold,” Jenkins would later tell police, tears streaming. “Like he’d been gone for hours.” Paramedics from Dearborn County EMS arrived within minutes, sirens wailing through the predawn streets, but it was too late. At St. Elizabeth Hospital in nearby Edgewood, doctors pronounced Emmett dead at 4:37 a.m. An autopsy confirmed the cause: asphyxiation compounded by neglect, with no drugs or trauma in his system—just the cruel mechanics of an unattended car seat.

The investigation unfolded with mechanical efficiency, peeling back layers of deception. Phillips-Steelsmith’s initial story to detectives was a patchwork of half-truths: she’d fed him at Kroger, checked on him periodically, dozed off only briefly. But bodycam footage from the scene contradicted her. As officers cordoned off the apartment, she paced the kitchen, wringing a dish towel, her eyes darting. “He was fine, I swear,” she repeated, but inconsistencies mounted. Phone records showed texts to friends at 7 p.m. complaining of “baby blues” and exhaustion, no mentions of checking Emmett. Surveillance from the apartment complex’s lobby captured her entering alone at 2:05 p.m., car seat in arms, and not emerging until the 911 call. A welfare check on Josh, who was working out of state as a truck driver, revealed his unanswered pleas: “How’s my boy? Send pics.”

By April 10, 2024, Phillips-Steelsmith was arrested on charges of reckless homicide and neglect of a dependent, her $200,000 bond a barrier she couldn’t breach. Dearborn County Prosecutor Lynn Deddens, a no-nonsense veteran with a track record of cracking down on child endangerment, built a watertight case. Forensic pathologist Dr. Elizabeth Mooney testified at the plea hearing, her diagrams chilling: “Emmett’s death was entirely preventable. At nine days old, his survival hinged on constant vigilance. The car seat, while safe for transit, becomes a deathtrap when misused.” Deddens drove home the negligence: no feedings for 14 hours meant Emmett’s blood sugar plummeted, exacerbating his vulnerability. “This wasn’t a momentary lapse,” she argued. “It was a full day of willful blindness.”

The plea deal came swiftly—guilty to reckless homicide in exchange for dropping the neglect charge—sparing a full trial but not the scrutiny. At sentencing on October 8, the courtroom swelled with locals: neighbors who’d heard the sirens, churchgoers from Phillips-Steelsmith’s evangelical congregation, and Emmett’s extended family, clad in black. Josh Steelsmith, 26, took the stand first, his voice cracking as he clutched a photo of the newborn swaddled in a hospital blanket. “Emmett had my eyes, Rae’s smile,” he said, tears carving paths down his bearded face. “I begged her to get help after the birth—she was overwhelmed, talking about postpartum fog. But this? Leaving our son to suffocate while you scrolled TikTok? I trusted you.” Josh revealed his own torment: Facebook posts chronicling his grief, from “My world ended yesterday” to pleas for Raeleigh’s return, convinced she was “a good mom deep down.” Their marriage, strained by the pregnancy—Raeleigh’s first, conceived amid a whirlwind romance—crumbled under the weight.

Phillips-Steelsmith’s mother, Carla Phillips, a 48-year-old factory worker, followed, her testimony a plea for mercy laced with denial. “Raeleigh’s always been sensitive, struggled with anxiety since high school,” she said, dabbing her eyes. “The baby came early, unexpected. She didn’t mean it—postpartum hit her like a truck.” But the judge was unmoved. McLaughlin, surveying the defendant, noted the absence of apology beyond a perfunctory “sorry.” “Your emotionlessness speaks volumes,” she intoned. “Emmett deserved a mother who saw him, not a prop in a car seat. Six years is the minimum, but know this: no sentence restores a life.” As deputies led her away in cuffs, Phillips-Steelsmith glanced back once—blank, unreadable—prompting gasps from the gallery.

Lawrenceburg, a town where the Ohio River laps at steel mill banks and Friday night lights illuminate high school football dreams, reeled from the case. Billboards for the Indiana Donor Network flanked news vans outside the courthouse, a grim irony given Emmett’s organ donation status—his corneas saved two children, a sliver of light in the darkness. Community forums buzzed: Was it malice or madness? Postpartum depression affects one in seven new mothers, per the CDC, manifesting in fatigue, detachment, and worst-case psychosis. Phillips-Steelsmith’s prenatal records showed red flags—untreated anxiety, a history of skipping therapy sessions—but no formal diagnosis. Advocates like the Indiana Maternal Mental Health Initiative decried the gaps: “We preach ‘it’s okay not to be okay,’ but where’s the follow-through? Raeleigh slipped through cracks that could swallow anyone.”

Josh, now raising awareness through a GoFundMe for infant safety gear donations, echoed that call. “Don’t judge her—help the next one,” he posted. “Emmett’s gone, but his story can save lives.” Nationally, the case amplified warnings: the Consumer Product Safety Commission reports over 100 car seat-related infant deaths since 2015, many from misuse. Experts like Dr. Rachel Moon, a pediatric sleep specialist, stress education: “Car seats are lifesavers on roads, but tombs indoors. Wake them, feed them, hold them.”

As fall leaves turn gold along the riverfront, Lawrenceburg heals slowly. A makeshift memorial at the apartment complex—teddy bears, a faded “Baby Emmett Forever” balloon—fades with the season. Phillips-Steelsmith begins her term at Rockville Correctional Facility, 150 miles north, where programs for maternal offenders offer a shot at redemption. But for a town forever scarred, the image lingers: a mother unmoved, a baby unheard. In the quiet hours, Emmett’s truth whispers: vigilance is love’s sharpest edge.

News

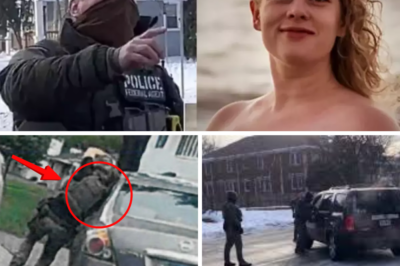

ICE Agent Involved in Fatal Shooting of Renee Good Previously Dragged 300 Feet by Vehicle in Bloomington Incident

Minneapolis, Minnesota – January 20, 2026 — The U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agent who fatally shot 37-year-old Renee…

Renee Good’s Family Refuses to Back Down: They’ve Quietly Retained One of America’s Top Attorneys — and Are Now Preparing to Release the Final Audio Recording That Could Change Everything

The family of Renee Nicole Good, the 37-year-old Minneapolis mother fatally shot by a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)…

Zion Foster Breaks Social Media Silence with Heartwarming Video of Daughter Story Amid Reports of Split from Jesy Nelson

London, January 20, 2026 — In his first public post since reports emerged of his separation from Jesy Nelson, musician…

Jesy Nelson Confirms Split from Fiancé Zion Foster Amid Heartbreaking Reality of Twins’ SMA Diagnosis

In a development that has left fans reeling, former Little Mix singer Jesy Nelson has confirmed the end of her…

A Teacher Everyone Trusted — Then She Vanished: The Tragic Case of Linda Brown and Lingering Questions After Her Lake Michigan Death

In the tight-knit Bridgeport community of Chicago, Linda Brown was more than just a special education teacher at Robert Healy…

Ex-Husband in Ohio Dentist Murders Allegedly Used Fake Details to ‘Disguise’ Himself Before Killings, Expert Says

Columbus, Ohio – January 20, 2026 — New revelations in the high-profile double murder case involving an Ohio dentist and…

End of content

No more pages to load