They vanished into the mist-shrouded peaks of Zongolica’s Sierra—silent as ghosts, gone for over a decade… until the earth spat back a secret that chills the soul.

In the rugged heart of Veracruz’s Nahua lands, a family of five stepped off a dirt trail for a routine harvest check—and into oblivion. No screams, no tracks, just whispers of cartel shadows and ancient curses. Now, skeletal remains unearthed in a hidden ravine rewrite the nightmare: buried alive? Ritual sacrifice? Or a cover-up that spans governments? The truth’s jagged edges could unravel Mexico’s darkest underbelly.

Dare to dig deeper before it’s silenced again.

Uncover the bones that broke the silence →

Deep in the fog-enshrouded folds of the Sierra de Zongolica, where jagged peaks pierce the Veracruz sky like ancient obsidian blades, the Morales family set out on a crisp October morning in 2013 for what should have been a simple errand: checking coffee vines on their small hillside plot. Father Javier Morales, 42, his wife Rosa, 39, and their three children—teenagers Ana, 16, and Miguel, 14, plus the youngest, little Sofia, 8—waved goodbye to neighbors in their remote Nahua village of Paso Yanuli. They never returned. For 12 years, their absence haunted the indigenous community, a silent scar amid whispers of cartel incursions and government neglect. Then, on October 15, 2025, a landslide triggered by Tropical Storm Pilar unearthed a cluster of skeletal remains in a concealed ravine, thrusting the long-cold case back into the spotlight and reigniting debates over Mexico’s epidemic of disappearances.

The discovery, confirmed by Veracruz state forensic teams on October 17, has sent shockwaves through the Nahua heartland, a region already scarred by over 1,200 reported vanishings since 2006, according to the National Search Brigade. Preliminary DNA matches, announced by the Veracruz Attorney General’s Office (FGE), identified the bones as belonging to the Morales family with 98% certainty. “It’s them—unmistakably,” said Dr. Elena Vargas, lead anthropologist at the Xalapa Forensic Lab, during a tense press conference on October 18. “The dental records of the children, the healed fracture on Javier’s femur from a 2009 logging accident—it all aligns. But the how and why… that’s a wound reopened.”

The Sierra de Zongolica, a UNESCO-recognized biosphere reserve spanning 1,200 square kilometers of cloud forests and coffee fincas, is as beautiful as it is treacherous. Home to over 100,000 Nahua people—the largest indigenous group in Veracruz—its steep trails and perpetual mists have long been a smuggling corridor for everything from migrants to meth precursors. In 2013, the Zetas cartel, then at the zenith of their reign of terror, controlled swaths of the highlands, extorting farmers and clashing with rivals in brutal turf wars. The Morales, modest coffee growers who sold beans to local co-ops, lived on the fringes of this violence, their plot a 45-minute hike from Paso Yanuli, a cluster of thatched homes clinging to 2,000-meter elevations.

Eyewitness accounts from the day paint a deceptively ordinary picture. “Javier borrowed my machete for the underbrush—said the vines were overgrown after the rains,” recalled neighbor Tomas Huerta, 65, a weathered Nahua elder who last saw the family at 9 a.m. on October 12, 2013. “Rosa carried Sofia on her back; the boys lugged water jugs. They joked about the harvest yield—nothing amiss.” By dusk, as mist rolled in like a shroud, alarm bells rang. A search party of 20 villagers combed the trails by lantern light, calling into the void, but found only Javier’s battered straw hat snagged on a barbed-wire fence 500 meters from home. No blood, no struggle—just eerie quiet.

The initial response was hampered by the terrain’s isolation. Veracruz state police arrived 48 hours later, hampered by washed-out roads from seasonal downpours. The National Guard, still years from its 2019 formation, was absent; instead, a ragtag team of local federales and volunteer trackers fanned out, deploying sniffer dogs that traced scents to a sheer drop-off before losing the trail. “The dogs went mad at the edge—pawing, whining—but the ravine below was a 100-meter hell of vines and boulders,” said retired searcher Ramon Tlaxcala, who led the effort. Satellite imagery from the era, declassified in 2024 under Mexico’s transparency laws, shows no anomalies—no campfires, no vehicle tracks—fueling early theories of a simple hiking mishap.

But skepticism brewed quickly. The Morales weren’t novices; Javier, a former municipal guide, knew the sierra like his own veins, having navigated it since boyhood. “They didn’t wander off—that path was etched in their steps,” insisted Rosa’s sister, Maria Morales, now 52, who has spearheaded annual memorials. Community leaders pointed fingers at the Zetas, notorious for “calentando la plaza” (heating up the turf) through forced disappearances to instill fear. In 2013 alone, Veracruz logged 300 enforced vanishings, per Human Rights Watch, many in indigenous zones like Zongolica where poverty— with 78% of locals below the poverty line, per CONEVAL 2024 data—made resistance futile.

As days stretched to weeks, the case calcified into legend. Media coverage, sparse amid the national frenzy over the Iguala mass kidnapping that September, framed it as “another sierra ghost story.” Conspiracy swirled: cartel reprisal for Javier’s rumored tips to anti-Zetas vigilantes? A botched migrant smuggling gone awry, with the family as unwitting mules? Or darker still, ties to the 2007 case of Ernestina Ascención Rosario, a Nahua elder found beaten on a Zongolica trail, gasping in Nahuatl about “green-clad strangers” who assaulted her—a euphemism locals decoded as military personnel amid Calderón’s drug war militarization. Ernestina’s death, ruled a homicide but unsolved, echoed in murals adorning Paso Yanuli’s chapel: faded portraits of the Morales beside pleas for justice.

Years passed in agonizing limbo. The FGE classified the case as “non-located persons” in 2015, archiving it amid 4,000 similar Veracruz files. Families like the Morales turned to collectives: Colectivo de Búsqueda de Mujeres Desaparecidas and Madres Buscadoras de Sonora, who trained locals in forensic anthropology. Annual treks to the sierra, marked by copal incense and marigold offerings, kept the flame alive. “We dig with hands and hearts—because the state forgets,” said activist Brenda Espinoza, whose group unearthed 15 clandestine graves in Zongolica since 2020, mostly Zetas victims from the 2010s.

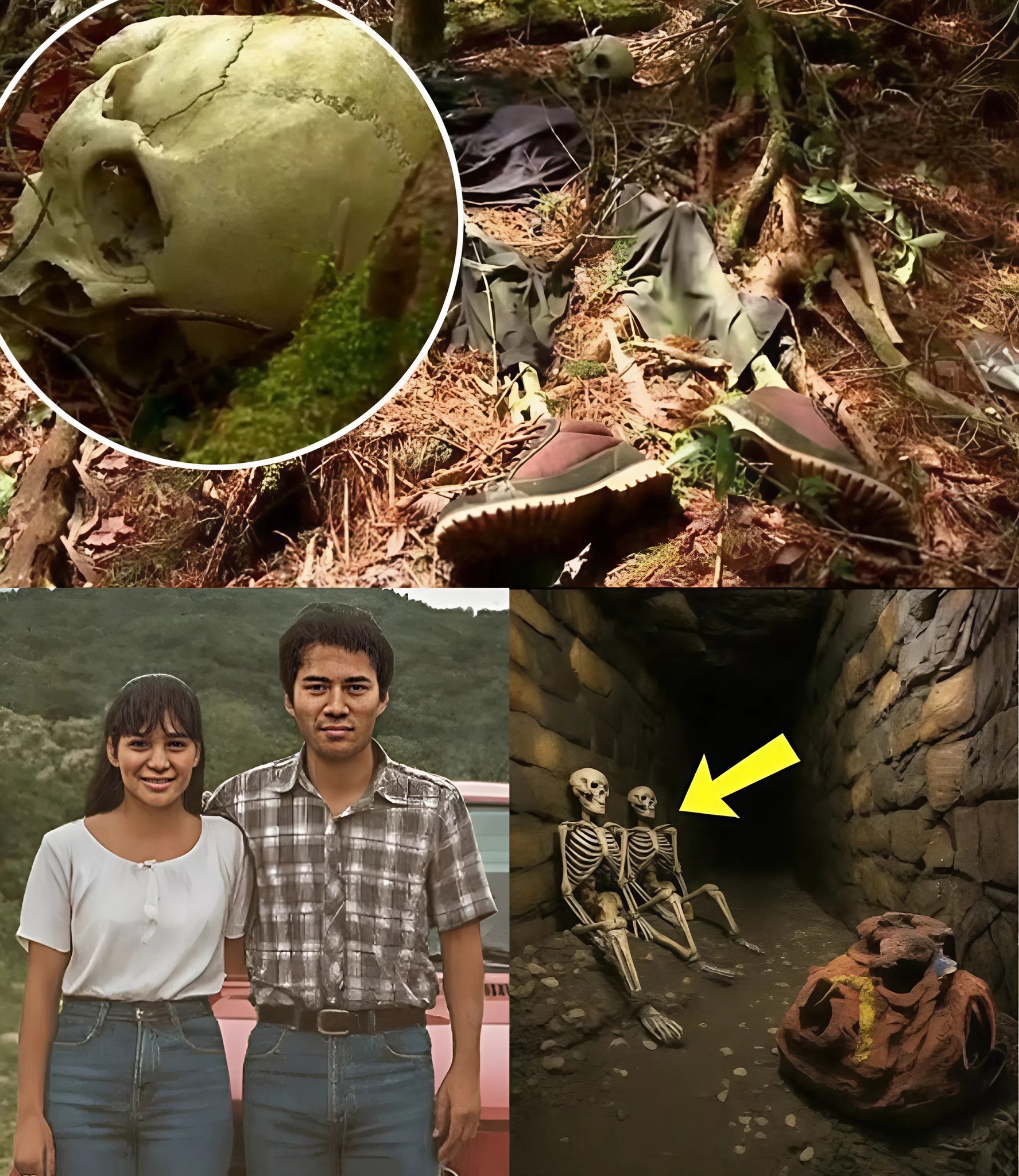

The 2025 breakthrough came courtesy of nature’s indifference. Tropical Storm Pilar, barreling through Veracruz on October 13, dumped 300 millimeters of rain in 24 hours, triggering landslides across the Sierra Madre Oriental. A routine drone survey by the National Civil Protection agency, mapping erosion risks, spotted an anomaly: a yawning gash in a remote ravine near the Morales’ finca, exposing bone fragments amid uprooted ceiba trees. Ground teams rappelled in on October 15, unearthing a grim tableau: five partial skeletons, bound at the wrists with decayed nylon cords, interred in shallow pits under a meter of soil and leaf litter. Accompanying artifacts—a child’s beaded bracelet matching Sofia’s description, Javier’s monogrammed belt buckle—sealed the identification.

Forensic details, released piecemeal to avoid contaminating the probe, paint a harrowing end. “Blunt force trauma to the skulls, consistent with rocks or rifle butts; asphyxiation likely from soil inhalation,” Vargas detailed, her voice steady but eyes weary. No gunshot residue, no blade marks—suggesting a hasty, improvised burial post-beating. Carbon dating pegs time of death to late 2013, aligning with the disappearance. Toxicology on preserved bone marrow showed no drugs, ruling out overdose scenarios. The bindings imply captivity, perhaps hours or days, before execution-style interment.

Investigators now pivot to motive. The FGE, under Governor Rocío Nahle’s administration, reactivated the case with a $500,000 reward for tips, enlisting Interpol for cross-border leads. Early whispers implicate ex-Zetas operatives, now fragmented into “Los Escorpiones,” who dominated Zongolica’s poppy fields in 2013. A 2024 DEA report, leaked to ProPublica, flags the sierra as a fentanyl hub, with 200 disappearances tied to “tax” collections on farmers. “The Morales may have refused a quota—coffee land repurposed for opium,” speculated retired federales captain Luis Herrera, who patrolled the zone. Alternatively, human rights groups like Amnesty International invoke “state facilitation”: Army checkpoints in 2013 ignored cartel traffic, per declassified SEDENA logs obtained via FOIA equivalents.

The unearthing has galvanized the Nahua community, long wary of outsiders. In Paso Yanuli, a September 28 vigil drew 500, blending Catholic rosaries with prehispanic chants to Xipe Totec, the flayed god of renewal. “The bones cry for their names,” intoned shaman Xochitl Nahua, leading a procession to the site, now cordoned by yellow tape fluttering like prayer flags. Families of other vanishings— the 2021 duo of lawyers Luz Edith Acevedo and Julio César Lara, last seen interviewing in Magdalena; or the June 2025 quartet from Comalapa, including teen Mercedes Abraham Colotl, whose bodies surfaced in Río Blanco—joined in solidarity, demanding a “verdad commission” modeled on Argentina’s dirty war tribunals.

Nationally, the case amplifies Mexico’s crisis: 110,000 disappeared since 1964, per the RNPDNO registry, with Veracruz third-worst at 6,000+. Indigenous zones bear disproportionate brunt—Nahua women 40% more likely to vanish, per a 2023 INPI study, often trafficked or killed in gender violence spikes. President Claudia Sheinbaum’s “Hugs, Not Bullets” policy, eschewing militarization, faces tests here: the Guard’s 2025 deployment to Zongolica for “reconstruction” post-Pilar has locals protesting, fearing repeats of Ernestina’s fate.

For the Morales kin, closure mingles with fury. Maria Morales, clutching a faded photo of Sofia’s gap-toothed grin, vowed at the vigil: “We bury them with honor, but the guilty? They rot in the light.” Sofia’s surviving aunt, Tia Carmen, 60, revealed a family secret: Javier had confided in 2013 about “armed men” pressuring for land deeds—possibly for wind farm leases eyed by foreign firms, a flashpoint in Nahua autonomy fights.

As forensic reports finalize—expected by November 15—the sierra whispers on. Landslides may unearth more; drones scan for similar anomalies. Experts like geologist Dr. Marco Ruiz warn of climate-fueled erosion exposing “graveyards of the forgotten.” In Xalapa’s bustling markets, vendors hawk Zongolica Phantom T-shirts, but for Paso Yanuli, it’s no merch: it’s a call to memoria viva.

The Morales saga, from harvest haze to ravine revelation, underscores Mexico’s fractured soul—where beauty cloaks brutality, and truth claws free only after blood feeds the soil. As one mural in the village chapel reads, in bold Nahuatl: “In axkan moyolnonotza—We do not forget the roots.” In Zongolica’s eternal mist, those roots run deep, demanding justice one unearthed bone at a time.

News

The revelation adds a new layer of gravity to an investigation already described by officials as “complex.

SHOCKING TWIST in the Ashley Flynn murder: Ohio cops just dropped the official autopsy bombshell — multiple gunshot wounds riddled…

Recent developments include reduced ventilator support as Maya began taking breaths independently

HER EYES FLUTTER WHEN SHE HEARS HER MOM SING. In the quiet of a Vancouver hospital room, a mother’s voice…

The family has urged the public to focus on compassion rather than politicizing the tragedy

“I NEVER THOUGHT THERE WOULD COME A DAY WHEN I WOULD HAVE TO BOW MY HEAD AND BEG THE WHOLE…

Police immediately launched an investigation and search efforts

A 2-YEAR-OLD VANISHES FROM HER BED OVERNIGHT… BUT NO ONE HAS SEEN HER IN WEEKS How does a toddler just…

The circumstances have left investigators and the community grappling with how an intruder could enter a family home

HOW DOES THIS HAPPEN IN A HOME WITH A FAMILY INSIDE? A quiet suburban night turns deadly at 2:30 a.m.—and…

Just hours after the tragedy unfolded, McKennly Smith posted a desperate plea on Facebook

BREAKING: JUST WON JOINT CUSTODY… THEN THIS A brutal 9-year custody war finally ends with Tawnia McGeehan regaining joint custody…

End of content

No more pages to load