In the quiet town of Oneida, nestled in the rolling hills of Outagamie County, Wisconsin, a nightmare unfolded behind the thin walls of a modest trailer home. On August 21, 2025, a frantic 911 call shattered the summer stillness. The voice on the line belonged to Walter Goodman III, a 47-year-old father, who breathlessly described his 14-year-old daughter as “seriously ill,” severely underweight, lethargic, and moaning in distress. Her breathing was ragged, she hadn’t eaten much in days, and he mentioned her self-harming behaviors and autism diagnosis. What followed was a rescue operation that peeled back layers of unimaginable cruelty, revealing a “house of horrors” where a child was systematically starved, isolated, and dehumanized over years. When rescuers arrived, they found the girl weighing a mere 35 pounds—less than many toddlers—locked in a bedroom, teetering on the edge of death. This is the story of her survival, the family’s depravity, and the slow grind toward justice.

The emergency unfolded with chilling rapidity. First responders from the Oneida Nation Police Department and local paramedics rushed to the Hattie Lane residence, a single-wide trailer that blended seamlessly into the rural landscape. Walter Goodman met them at the door, his explanations tumbling out in a mix of panic and deflection. He claimed his daughter had an eating disorder exacerbated by her autism, insisting she refused food and sleep, burning energy like a perpetual motion machine with the mental capacity of a 4- to 6-year-old. But as officers entered the dim, cluttered home, the truth hit like a gut punch. The girl lay curled on a bare mattress in a locked bedroom, her frail body the size of a 6- or 8-year-old child. She was unresponsive, her skin clammy and pale, her ribs protruding like the bars of a cage beneath translucent flesh. A large, fresh bruise marred her forehead, and pressure sores—angry red welts from prolonged immobility—dotted her hips and back. She was hypothermic, her core temperature dangerously low, and her blood sugar had plummeted to 24, a level that could induce coma or seizure.

Paramedics sprang into action, intubating her on the spot to stabilize her breathing before airlifting her via helicopter to Children’s Wisconsin in Wauwatosa, a specialized pediatric facility about 30 miles away. En route, doctors pumped her with intravenous fluids and glucose, fighting to keep her alive. At the hospital, the full extent of her suffering emerged in a barrage of scans, tests, and consultations. She was diagnosed with severe acute malnutrition, multi-organ dysfunction syndrome, respiratory failure, cardiac irregularities, severe hepatitis, and pancreatitis. Her liver and kidneys were failing, her heart strained from the relentless assault of starvation. Remarkably, she had no recent infections or acute illnesses to blame; this was chronic neglect, etched into her body over months—perhaps years. Medical experts later testified that her condition couldn’t have developed in mere days or weeks, as Goodman suggested. It was a slow, deliberate erosion, the kind that reasonable caregivers would have noticed and halted long before it reached this precipice.

As the girl fought for her life in the intensive care unit, investigators began piecing together the puzzle of how a child could vanish into plain sight. The trailer on Hattie Lane was no ordinary home; it was a pressure cooker of dysfunction, home to five adults and two children in a space barely larger than a school bus. Walter Goodman had gained custody of his daughter around 2020, after she lived with her biological mother. From that point, she was erased from the world—no school enrollment, no doctor’s visits, no playdates. Her last medical checkup was five years prior, a gap that screamed negligence. The household revolved around Goodman and his second wife, Melissa Goodman, 50, a woman so morbidly obese she was nearly bedridden, her days spent in a haze of immobility and fast-food deliveries. Their adult daughter from a previous marriage, Savanna LeFever, 29, mirrored her mother’s condition, her weight confining her to the trailer like a prisoner in her own skin. LeFever’s partner, Kayla Stemler, 27, was the outlier—the sole breadwinner, venturing out to a local job while the others festered in isolation. A teenage stepbrother, identified only by initials in court documents, flitted through the background, his role unclear but his presence a silent witness to the chaos.

Inside those walls, the girl’s existence was reduced to a shadow. Locked in her bedroom with a baby monitor camera trained on her every twitch, she was forbidden from wandering the trailer unescorted. Permission was required for bathroom breaks, and meals—if they could be called that—were rationed like contraband. Family members later admitted doling out Pediasure shakes, half-eaten sandwiches, or cold leftovers, always under Goodman’s watchful eye. He enforced a bizarre regime: no sweets, limited portions, and stern warnings against “overindulgence.” Yet, in the hospital, this narrative crumbled. Nursed back with three square meals a day and uninterrupted sleep, the girl perked up almost immediately. She devoured pancakes with glee, begged for M&Ms and tacos, even expressed a surprising fondness for vegetables—foods her father had deemed off-limits. “He would be mad at me for eating that much,” she confided to a social worker, her voice a fragile whisper. Far from the feral, non-verbal child her family portrayed, she engaged in age-appropriate conversations, her autism manifesting not as rejection of food but as a quiet resilience forged in adversity.

The investigation, spanning three grueling months, unearthed a digital trail of horror that turned stomachs and hardened resolve. Outagamie County Sheriff’s deputies and social services pored over seized phones, uncovering a group chat among Melissa, LeFever, and Stemler that read like a manifesto of malice. The girl was derided relentlessly: “dummy,” “stupid,” “manipulative little bitch.” One message from LeFever captured the casual cruelty: “She’s just so skinny, I’m scared she’s gonna die for real this time.” Another outlined the lockdown protocol: “She is not to be out of her room at all. Only give her water at specific times. Take the mattress out—she can sleep on the floor.” Physical punishment was normalized; Stemler confessed to wielding a belt for “discipline,” while LeFever admitted smacking the girl’s hands with a hairbrush for infractions like speaking out of turn. A family friend, interviewed under oath, recounted Goodman’s rants: “If I could leave her in the woods, I would,” or the chilling aside to the girl herself, “I wish I could kill you.” These weren’t outbursts of frustration; they were symptoms of a household where empathy had atrophied, replaced by control and indifference.

Neighbors, too, offered glimpses of the unseen tragedy. Pam Medina, who lived across the street, recalled the day of the rescue with haunting clarity. From her porch, she watched as firefighters cradled the “tiny” girl in their arms, her head lolling limply to one side, limbs dangling like a rag doll’s. “I didn’t even know a child lived there,” Medina said, her voice cracking with regret. The trailer had always seemed reclusive—curtains drawn, visitors scarce—but the frequent Walmart grocery hauls, sometimes twice a day, now struck her as ominous. “They ordered so much food, pallets of it. How could they let her starve?” Medina agonized over missed signs, vowing she would have stormed the door if she’d suspected the truth. Her story echoed a community’s collective guilt: in a tight-knit town like Oneida, where the Oneida Nation’s cultural heritage fosters strong communal bonds, how had this atrocity festered undetected?

By mid-November 2025, the dam broke. On November 11, authorities swooped in with arrest warrants, hauling Goodman, LeFever, Stemler, and finally Melissa—charged last after forensic review of the chats—into Outagamie County Jail. Each faced a litany of felonies: three counts of chronic neglect of a child resulting in great bodily harm, and two counts causing emotional damage. Wisconsin law defines chronic neglect as a pattern of failing to provide food, medical care, clothing, shelter, or education—essentials that sustain life and dignity. Conviction on all counts could net decades in prison, a sentence prosecutors vowed to pursue with unrelenting vigor. Outagamie County Assistant District Attorney Julie DuQuaine, a veteran of 25 years in the trenches of child welfare cases, called this the most egregious she’d ever seen. “It’s a miracle she’s alive,” DuQuaine told reporters, her words laced with barely contained fury.

In court, the proceedings unfolded like a somber theater of reckoning. Court Commissioner Brian Figy, presiding over initial appearances, didn’t mince words. Gazing at the defendants—Goodman stoic, Melissa tearful, LeFever and Stemler subdued—he labeled the trailer a “house of horrors” and the girl’s survival “by the grace of God.” Bonds were set high: $150,000 cash for Melissa, with similar amounts for the others. Preliminary hearings loomed—Goodman’s on November 19, Stemler’s the next day, LeFever’s on November 20—each a step toward trial, where the evidence would be laid bare for a jury to judge.

Amid the legal maelstrom, glimmers of hope emerged for the victim. Her grandparents, stepping in as kin, reported steady progress: weight gain, physical growth spurts, and a spark of normalcy returning. Discharged from the hospital but under protective supervision, she now resides in a secure, undisclosed location, far from Hattie Lane’s shadows. Therapists note her cognitive function aligns with peers her age, debunking the family’s myth of profound disability. Her autism, they emphasize, is a spectrum—not a license for abuse, but a call for tailored support that was cruelly withheld. She dreams of simple joys: school, friends, a bedroom without locks. “I like pancakes,” she told a counselor shyly, a declaration that carries the weight of reclaimed agency.

This case ripples beyond Oneida’s borders, exposing fissures in America’s child protection net. Rural isolation amplifies risks; in areas like Outagamie County, where resources stretch thin, mandatory reporting laws rely on vigilant eyes—teachers, doctors, neighbors—that were absent here. Autism misconceptions compound the peril: too often, behaviors are misread as defiance rather than cries for help, enabling abusers to hide behind diagnoses. Nationally, child neglect claims over 1,700 lives yearly, per federal data, with malnutrition a silent killer in homes of apparent normalcy. Experts advocate for bolstered home visits, AI-flagged welfare checks, and community education to pierce the veil of secrecy.

As winter blankets Wisconsin in snow, the Goodman trailer stands vacant, a scarred monument to failure. Justice inches forward, but true healing demands more: systemic reforms, communal awakening, and an unyielding commitment to the vulnerable. For the 14-year-old who clawed back from 35 pounds of despair, her story isn’t just one of horror—it’s a clarion call. She survived not despite the odds, but to remind us: every child deserves a table set with abundance, not scraps of cruelty. In her quiet strength lies the potential for change, a fragile flame against the dark.

News

“She Was Just a Poet, a Mother, and a Wife… Then an ICE Agent Shot and Killed Her Right on Her Street”: The Shocking Death of Renée Nicole Good – What Really Happened Hours After Dropping Her Children Off at School

On the morning of January 7, 2026, Renée Nicole Good, a 37-year-old U.S. citizen, poet, writer, and devoted mother of…

NEW VIDEO EMERGES: Chilling Footage Reveals Renee Good’s Final Moments Before Fatal ICE Shooting – Her Last Words Expose a Desperate Plea as Bullets Fly

The release of new cellphone footage has intensified the national outcry over the fatal shooting of 37-year-old Renee Nicole Good…

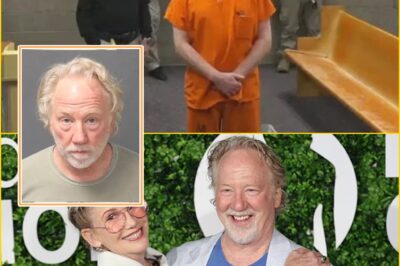

“Your Hands Used for Saving People, Not Killing Them”: Judge’s Stark Words Leave Accused Surgeon Michael David McKee Collapsing in Court During First Hearing in Tepe Double Murder Case

The Franklin County courtroom in Columbus, Ohio, fell into stunned silence on January 14, 2026, as Judge Elena Ramirez delivered…

“This is Not How It Was Supposed to End”: Timothy Busfield’s Grave Court Appearance as Judge Denies Bail in Shocking Child Sex Abuse Case

In a courtroom moment that stunned observers and sent ripples through Hollywood and beyond, veteran actor and director Timothy Busfield,…

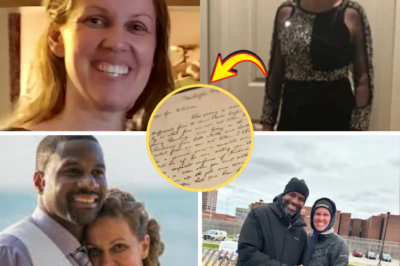

Husband of Chicago Teacher Linda Brown Discovers Heartbreaking Suicide Note Revealing Her Final Reasons for Leaving and Ending Her Life

The tragic death of Linda Brown, the 53-year-old special education teacher at Robert Healy Elementary School in Chicago, has taken…

“She Escaped the Fire… Then Turned Back”: The 18-Year-Old Hero Who Ran into the Flames at Crans-Montana — and Is Now Fighting for Her Life

In the chaos of the deadly New Year’s Eve fire at Le Constellation bar in the Swiss ski resort of…

End of content

No more pages to load