In the quiet suburbs of Winnipeg, Manitoba, where the prairies stretch endlessly under vast Canadian skies, a story unfolded that would shatter the illusions of safety we hold dear for our children. It is a tale of innocence lost, of systems designed to protect crumbling under their own weight, and of a little girl named Phoenix Sinclair whose brief life became a haunting indictment of human failure. Five-year-old Phoenix, with her wide eyes and fleeting smiles, was not just a victim of unspeakable cruelty from those who should have loved her most. She was a casualty of a web of indifference spun by family, friends, and the very institutions sworn to safeguard the vulnerable. For nine agonizing months, her parents hid her death, collecting welfare checks in her name while her tiny body lay discarded in a landfill like forgotten refuse. This is the story of Phoenix Sinclair—a child who deserved the world but received only shadows.

The narrative of Phoenix’s life and death has been recounted in whispers and headlines for nearly two decades, but it finds fresh, poignant resonance in the voice of Brooke Makenna, a storyteller whose podcast, Motives & Malice, peels back the layers of tragedy with unflinching empathy. In episodes dedicated to Phoenix’s memory, Makenna doesn’t just recite facts; she breathes life into the forgotten corners of this horror, urging listeners to confront the uncomfortable truth: how could so many eyes miss the signs? How could a system, meant to be a fortress, become a sieve through which a child’s pleas slipped away? As Makenna weaves the threads of Phoenix’s story, she paints a portrait not of monsters alone, but of a society that turned away when it mattered most. Phoenix was born on April 23, 2000, in the heart of Winnipeg, to parents Samantha Kematch and Steve Sinclair. From the outset, her arrival was shadowed by instability. Both parents carried the scars of their own troubled upbringings—Kematch, a young Indigenous woman from the Fisher River Cree Nation, had already lost custody of an older child to the state’s permanent wardship. Sinclair, her father, was a man prone to absence, his affections as fleeting as prairie winds.

Phoenix entered the world not in the warmth of a family home, but under the watchful eye of Child and Family Services (CFS), Manitoba’s child welfare agency. Deemed too unprepared to parent, Kematch and Sinclair surrendered their newborn to temporary foster care mere hours after her birth. For the first five months of her life, Phoenix bounced between a shelter and foster families, her tiny form a pawn in a game of supervised visitations. Social workers, overburdened and undertrained, mandated parenting classes and ongoing assessments before reuniting her with her parents in September 2000. It was a conditional mercy, laced with red tape and hope. But as Makenna notes in her retelling, those early interventions were little more than checkboxes on a form—superficial audits that failed to probe the deeper fractures in the family dynamic.

By the spring of 2001, Phoenix had a baby sister, Echo, born on April 29 amid another round of CFS evaluations. The sisters’ lives, though, were anything but harmonious. Domestic violence erupted in the home that June, drawing police to the door after a neighbor’s frantic call. Bruises bloomed on young skin, and whispers of neglect filtered through the cracks. Kematch and Sinclair separated soon after, leaving Steve to shoulder the caregiving alone—or so it seemed. In reality, Phoenix spent most of her days in the care of Kim Edwards, a family friend whose home became a reluctant sanctuary. Edwards, described by those who knew her as kind but overwhelmed, fed and clothed the girl while Sinclair drifted in and out, his reliability as thin as the summer ice on the Red River.

Tragedy struck the family again on July 15, 2001, when four-month-old Echo succumbed to a respiratory infection, her tiny body too frail to fight. The death certificate listed natural causes, but questions lingered like smoke from a dying fire. CFS files, reopened in the wake of the loss, documented concerns about Phoenix’s safety—reports of inadequate supervision, of a father more interested in his own demons than his daughter’s well-being. Yet, by early 2002, the file was quietly closed. No follow-up visits. No alarms raised. Phoenix, now a toddler with curls framing her cherubic face, slipped back into the ether of unchecked lives.

The cracks widened in February 2003, when a routine hospital visit revealed a horrifying truth: a chunk of Styrofoam had been lodged in Phoenix’s nose for nearly four months, a foreign invader born of neglect. Doctors marveled at her survival, prescribing antibiotics while eyeing her father warily. Would he administer the medicine? Or would it join the pile of unheeded responsibilities? Alarms finally sounded, and in June 2003, Phoenix was apprehended by CFS and placed under Edwards’ temporary guardianship. For a brief, illusory period, stability reigned. Edwards enrolled her in playgroups, where Phoenix’s laughter echoed like a promise of brighter days. But shadows loomed. In April 2004, Kematch reappeared, spiriting Phoenix away for what was meant to be a short visit. It stretched into permanence.

Kematch had found a new partner: Karl “Wes” McKay, a man whose charm masked a volcanic temper. Together, they built a life in Winnipeg’s underbelly, Phoenix at its precarious center. Steve Sinclair, meanwhile, packed his bags for Ontario, severing ties with a phone call that echoed his earlier abandonments. By fall 2004, Phoenix was enrolled at Wellington School for nursery, her name inked on registration forms with optimistic flourish. Teachers waited for her arrival, prepared lesson plans for a girl they never met. Kematch and McKay, evading questions, claimed she was “with relatives.” New CFS files flickered open in November 2004, after the birth of their son, and again in March 2005, sparked by anonymous tips of bruises and hunger. Each time, the doors slammed shut almost as quickly as they creaked open—files deemed “low risk,” investigations aborted for lack of “immediate danger.”

In April 2005, the family uprooted to the Fisher River Cree Nation, a remote reserve where oversight thinned like morning mist. Phoenix, now five, shared the cramped home with her half-brother, McKay’s sons from a previous relationship—boys aged 12 and 14, witnesses to the unraveling—and the couple’s infant. A final CFS file opened in May, prompted by a relative’s call decrying neglect: the girl was dirty, underfed, vanishing for days. A social worker’s note scribbled urgency, but action lagged. Home visits were scheduled and canceled; calls went unreturned. Phoenix’s world shrank to a basement room, cold and foul, where she slept on a bare mattress amid the stench of mildew and despair.

What transpired in those final weeks defies comprehension, a descent into barbarity that Makenna recounts with a voice heavy with sorrow. Phoenix became a target in a household ruled by rage. McKay, fueled by alcohol and resentment, invented “games” of torment: “choking the chicken,” where he squeezed her throat until blackness claimed her; target practice with a BB gun, welts rising like cruel constellations on her skin. Kematch, once a mother herself, watched impassively or joined in, forcing the child to eat her own vomit after meals withheld as punishment. Witnesses later testified to the girl’s pleas—”Please, stop”—met with blows from belts, fists, and boots. She was isolated, forbidden from speaking, her existence reduced to a ghost in her own home.

On June 11, 2005, the end came swiftly and savagely. McKay’s 12-year-old son recounted the horror in hushed tones during the inquiry: a beating that lasted over 15 minutes, Phoenix’s small body crumpling under unrelenting force while Kematch stood by, unmoved. Left alone in the basement, the boy checked on her later to find silence—no breath, no pulse. Panic set in, but not confession. The couple wrapped her body in plastic, drove to the Fisher River landfill under cover of night, and buried her shallowly amid the garbage. To the world, Phoenix lived on. They returned to Winnipeg, claiming welfare benefits in her name, even as her absence gnawed at the edges of their lie. A second child arrived in December 2005, a boy they paraded as proof of normalcy.

The facade cracked in March 2006, nine months after her death. McKay’s ex-partner, alerted by her sons’ whispers of the “accident,” confronted the couple. Desperate, Kematch and McKay produced a stranger’s child, passing her off as Phoenix in a bid for silence. The boys, burdened by their secret, broke. Police descended, arrests followed on March 13, and five days later, a landfill worker unearthed the unimaginable: a child’s remains, decomposed but identifiable by a silver bracelet etched with “Phoenix.” DNA confirmed the nightmare. Winnipeg reeled; protests erupted outside CFS offices, demanding accountability.

The trial, unfolding in the sterile confines of a courtroom in 2008, laid bare the depravity. Prosecutors painted a portrait of premeditated sadism, bolstered by the boys’ testimonies—reluctant but damning. McKay and Kematch, once partners in crime, turned on each other, each blaming the other’s demons. On December 3, 2008, a jury convicted them of first-degree murder. Life sentences without parole for 25 years were handed down, appeals crumbling like dry earth. Yet justice for Phoenix felt hollow; her killers would breathe free air long after her memory faded from headlines.

The true reckoning came through the Phoenix Sinclair Inquiry, launched in 2011 under Commissioner Ted Hughes, a veteran jurist whose report, The Legacy of Phoenix Sinclair: Achieving the Best for All Our Children, dropped like a thunderclap in January 2014. Spanning two volumes and 62 recommendations, it dissected a system in freefall. From Phoenix’s birth, CFS had opened 37 files on her—averaging one every three months—yet each dissolved into inaction. Social workers, juggling caseloads of 50 or more, lacked cultural sensitivity for Indigenous families like Kematch’s, ignoring the intergenerational trauma of residential schools and poverty. Training was perfunctory; information silos between agencies—schools, police, health services—ensured warnings echoed unheard.

Hughes highlighted pivotal failures: the 2003 Styrofoam incident, dismissed as a fluke; the 2005 neglect report, buried under bureaucratic inertia. School enrollment fraud went unchecked because no one knocked on the door. Even after Echo’s death, no deep dive into sibling risk. The inquiry cost Manitoba upwards of $14 million, its hearings a parade of tearful testimonies from workers haunted by “what ifs.” Makenna, in her podcast, amplifies these voices, quoting Hughes’ poignant charge: “Phoenix Sinclair was failed by every system meant to protect her.” The report called for mandatory inter-agency data sharing, culturally attuned training, reduced caseloads, and school-based welfare checks. Manitoba responded with reforms—a formal apology from Premier Greg Selinger, millions poured into Indigenous child services, and Phoenix’s Law, mandating reviews for high-risk returns to parents.

Today, nearly 20 years on, Phoenix’s legacy lingers in the prairies’ chill winds. Her grave at Brookside Cemetery, marked by a simple stone, draws quiet pilgrims—families, advocates, survivors—who leave toys and flowers as talismans against forgetting. Brooke Makenna’s retelling ensures her story endures, not as a relic of horror, but as a clarion call. In The Little Girl Forgotten, she muses on the “dark secret” that allowed evil to flourish: our collective aversion to the uncomfortable gaze. Phoenix Sinclair was more than a statistic in a failed file; she was a dreamer who named herself after a bird of rebirth, only to be extinguished before her wings could spread.

Her death exposed the rot in Canada’s child welfare underbelly, where Indigenous children like her—disproportionately apprehended yet poorly protected—face odds stacked against them. Statistics from the era painted a grim picture: Manitoba’s apprehension rate tripled the national average, with First Nations kids comprising 90% of CFS cases. Reforms have bent the arc—caseloads trimmed, cultural liaisons hired—but gaps persist. A 2023 audit revealed ongoing delays in high-risk interventions, echoes of Phoenix’s silence.

As Makenna concludes her episodes, she turns to the boys who survived that house of horrors—now men, their psyches scarred but resilient. They spoke not for vengeance, but for change, their words a bridge from basement despair to daylight hope. Phoenix’s story is a mirror, reflecting our complicity in the shadows we allow. In honoring her, we must ask: Who is the next Phoenix, waiting in the cold? And will we finally listen?

News

“She Was Just a Poet, a Mother, and a Wife… Then an ICE Agent Shot and Killed Her Right on Her Street”: The Shocking Death of Renée Nicole Good – What Really Happened Hours After Dropping Her Children Off at School

On the morning of January 7, 2026, Renée Nicole Good, a 37-year-old U.S. citizen, poet, writer, and devoted mother of…

NEW VIDEO EMERGES: Chilling Footage Reveals Renee Good’s Final Moments Before Fatal ICE Shooting – Her Last Words Expose a Desperate Plea as Bullets Fly

The release of new cellphone footage has intensified the national outcry over the fatal shooting of 37-year-old Renee Nicole Good…

“Your Hands Used for Saving People, Not Killing Them”: Judge’s Stark Words Leave Accused Surgeon Michael David McKee Collapsing in Court During First Hearing in Tepe Double Murder Case

The Franklin County courtroom in Columbus, Ohio, fell into stunned silence on January 14, 2026, as Judge Elena Ramirez delivered…

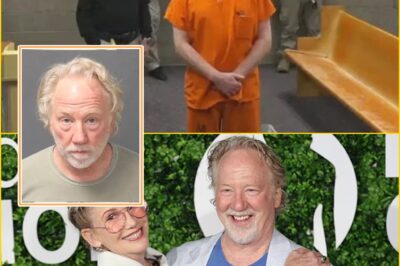

“This is Not How It Was Supposed to End”: Timothy Busfield’s Grave Court Appearance as Judge Denies Bail in Shocking Child Sex Abuse Case

In a courtroom moment that stunned observers and sent ripples through Hollywood and beyond, veteran actor and director Timothy Busfield,…

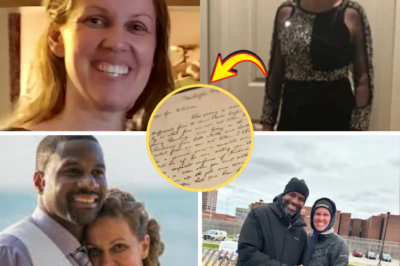

Husband of Chicago Teacher Linda Brown Discovers Heartbreaking Suicide Note Revealing Her Final Reasons for Leaving and Ending Her Life

The tragic death of Linda Brown, the 53-year-old special education teacher at Robert Healy Elementary School in Chicago, has taken…

“She Escaped the Fire… Then Turned Back”: The 18-Year-Old Hero Who Ran into the Flames at Crans-Montana — and Is Now Fighting for Her Life

In the chaos of the deadly New Year’s Eve fire at Le Constellation bar in the Swiss ski resort of…

End of content

No more pages to load