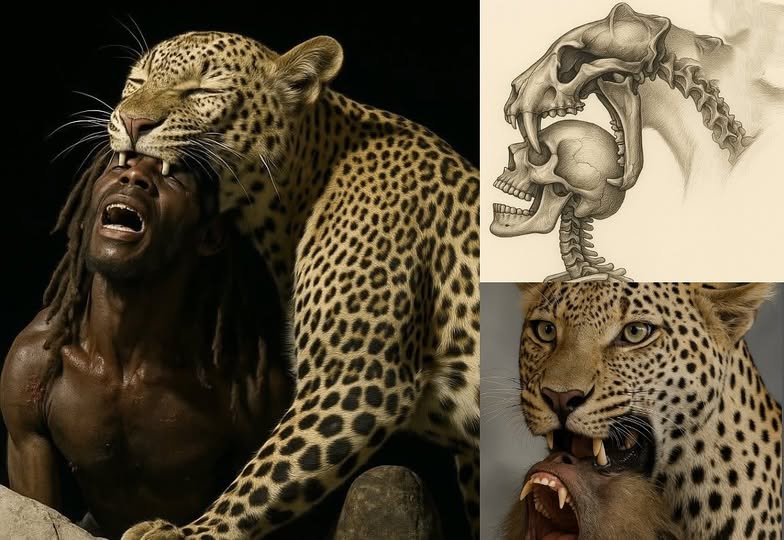

HUMANITY HUNTED: Were Our Ancestors PREY to MONSTROUS BEASTS?! 🦴🔥😱

Deep in a forgotten cave, a horrifying truth claws its way out: human bones scarred with savage bite marks and claw gouges—proof we weren’t always top dog! These aren’t just fossils; they’re screams frozen in time, buried with eerie rituals to appease UNKNOWN predators. Were these nightmare creatures just extinct monsters, or something SINISTER erased from history? 😈 The cave walls whisper of a terror so ancient it could rewrite who we are. Dare to face the truth before it hunts you down.

In the shadowed depths of a newly uncovered cave system in South Africa’s Cradle of Humankind, archaeologists have stumbled upon a discovery that could upend our understanding of early human survival. Unearthed amid limestone chambers, a trove of human fossils—dating back roughly 2 million years—bears chilling evidence: deep claw marks, jagged bite impressions, and signs of ritual burial that suggest our ancestors weren’t always the dominant hunters of prehistory. Instead, they may have been prey to colossal, unknown predators whose traces have eluded science until now. This isn’t just a pile of bones; it’s a window into an era when humanity cowered in fear of beasts that ruled the night.

The find, dubbed the “Malapa Terror Cache” by its discoverers, emerged during a 2024 excavation led by Dr. Thandiwe Nkosi of the University of the Witwatersrand. Her team was probing a lesser-known extension of the Malapa Fossil Site—famous for the 2008 discovery of Australopithecus sediba—when they hit a chamber packed with 47 hominin bones, likely from early Homo or Australopithecus species. “The moment we saw the gouges, we froze,” Nkosi told reporters, her gloved hands tracing a femur etched with claw marks. “These aren’t scavenging scars. The depth, the spacing—it’s predation, deliberate and brutal.” Alongside the bones were ochre-stained pebbles and ash layers, hinting at ritualistic burials—a desperate attempt, perhaps, to appease or evade whatever hunted them.

A Predator Unlike Any Known

The bone markings are the smoking gun. CT scans reveal bite impressions with puncture depths exceeding those of modern lions or hyenas—South Africa’s top Pleistocene carnivores. The claw gouges, some penetrating bone, suggest a predator with talons sharper and longer than any known big cat or bear. “We’re looking at something massive, likely 800-1,000 pounds, with a jaw force off the charts,” says paleoanthropologist Dr. Marcus Bello of Stellenbosch University, who analyzed the fossils. “The closest match might be Dinofelis, a saber-toothed cat, but these marks are too wide, too deep.” One chilling detail: several skulls show crush patterns, as if gripped by jaws capable of splintering bone like dry twigs.

Skeptics urge caution. “Ancient caves are taphonomic traps—bones get jumbled, marks misread,” argues Dr. Sarah Henshaw, a taphonomist at the University of Cape Town. She points to the Sterkfontein Caves, where hominin remains often bear hyena or leopard marks, mistaken for “monster” attacks in early studies. Yet the Malapa bones tell a different story: 60% show consistent predation trauma, with no signs of post-mortem scavenging. “Scavengers gnaw; these were bitten clean through,” Bello counters. Isotope analysis bolsters his case: the victims’ bones show low nitrogen levels, suggesting a diet heavy on plants—typical of early hominins, but also easy prey for a top-tier carnivore.

Echoes of Ancient Terror

The ritual elements deepen the mystery. The ash layers, dated to roughly 1.8-2.1 million years ago, predate widespread evidence of controlled fire among hominins, raising eyebrows. “If these were fires, they were small, deliberate—possibly ceremonial,” says Nkosi. The ochre-stained pebbles, arranged in crude circles around some skeletons, mirror proto-ritual behaviors seen in later Homo sapiens burials, like those at Border Cave (40,000 years old). One child’s skeleton, its tiny wrists bound with fossilized vine, was buried beneath a flat stone etched with zigzag lines—a symbol some link to shamanic wards against malevolent forces. “This wasn’t random,” Nkosi insists. “They feared something specific, enough to bury their dead with offerings to keep it at bay.”

Folklore offers haunting parallels. San Bushman tales, preserved orally for millennia, speak of the “Ngoloko,” a shadow-beast with claws like sickles that hunted humans under starless skies. Similar legends dot Africa: the Nandi bear in Kenya, a hulking predator blending bear and hyena traits, or Zimbabwe’s “Mngwa,” a catlike terror said to stalk until the 1930s. “These stories aren’t just campfire yarns,” says ethnohistorian Dr. Lindiwe Mokoena. “They’re survival warnings, encoding real threats our ancestors faced.” The Malapa find aligns with such tales: a predator so fearsome it shaped early human behavior, forcing rituals to placate its wrath.

What Was the Beast?

Speculation runs wild. Could it be an unknown Dinofelis variant, evolved for larger prey like Australopithecus? Fossils of these “false saber-tooths” show they hunted hominins, but nothing matches the Malapa marks’ scale. A rogue bear, like the extinct Agriotherium? Possible, but African bear fossils are scarce post-Pliocene. Some whisper of Megantereon, a jaguar-sized saber-tooth with bone-crushing jaws, though its range leaned European. More fringe theories point to cryptids—surviving relics like the “Tsavo Man-Eaters” on steroids—but paleontologists scoff. “We don’t need Bigfoot,” Bello quips. “Evolution’s weird enough.”

The cave’s geology offers clues. Stalagmite growth pegs the chamber’s sealing at 1.7 million years ago, trapping the bones in a time capsule. Nearby, fossilized tracks—too eroded for precise ID—show a four-legged creature with 18-inch strides, dwarfing known carnivores like Panthera leo atrox. Pollen traces in the ash suggest a savanna lush with acacias, ideal for ambush predators. “Imagine a hominin troop foraging at dusk,” says Nkosi. “Something huge, fast, and smart hits from the shadows. You’d invent gods to explain it.”

Rewriting the Human Story

The implications are profound. If early humans were prey, not apex hunters, it reshapes our evolutionary narrative. “We’ve romanticized Homo as the spear-wielding conqueror,” says Mokoena. “But these bones say we were lunch first—our brains grew to outsmart claws, not just to hunt.” Tool use, group living, even proto-religion may trace to fear of such beasts. Sites like Swartkrans, where Paranthropus bones bear Dinofelis marks, already hinted at this, but Malapa’s scale—dozens of victims, ritualized—suggests a prolonged, existential threat.

Critics, however, see exaggeration. “Caves concentrate remains; it’s not a horror movie,” Henshaw argues. “Rituals? Could be natural ochre staining or wind-blown ash.” She notes that modern leopards still drag kills into caves, mimicking mass graves. But the vine-bound child and etched stone tilt toward intent. “Natural processes don’t carve zigzags,” Nkosi retorts. Ongoing DNA tests aim to clarify: Were these victims a single clan? Did they share the cave with their killer?

A Haunting Legacy

The find stirs South Africa’s soul. The Cradle of Humankind, a UNESCO site, draws thousands yearly to ponder human origins. Now, locals like tour guide Sipho Mabuza feel a chill. “My grandmother warned of spirits in these hills—beasts that ate our kin,” he says, eyeing Malapa’s entrance. “This proves she wasn’t joking.” Sangoma healers have begun rituals at the site, scattering herbs to “calm the hunted.”

As excavators plan a 2026 push deeper into the cave—potentially unearthing the predator’s own bones—the world watches. Was it a freak of evolution, a relic of a lost genus, or just an oversized Dinofelis with a taste for hominins? The fossils don’t lie, but they don’t confess either. For now, Malapa’s bones whisper a humbling truth: Long before we ruled the earth, something else ruled us. In the cave’s eternal dark, humanity’s first fear still lurks, waiting for its name.

News

Schumaker initially claimed the toddler fell or injured himself accidentally but later admitted to losing control and striking him.

💥 FROM TEARS TO TERROR: 16-year-old Dylan Shoemaker sobbed in court, begging for mercy over the brutal d3ath of the…

In the execution chamber, Nichols made a final statement expressing sorrow

⚡ CHILLING END TO A 37-YEAR NIGHTMARE: Harold Wayne Nichols, the “Red-Headed Stranger,” has just been ex3cuted by lethal injection…

A second officer joined the effort but also fell through; both made it back to shore and were hospitalized for evaluation

❄️ “My husband! Please save him first!” — These desperate final words from a woman fighting for her life in…

Those simple, everyday words — now remembered as his last conversation with his mom — have brought fresh waves of grief to the family

🌟 A TRUE HERO AMONG US: 12-year-old Abel Mwansa didn’t run away from danger — he ran TOWARD it to…

The investigation continues into the firearm, digital communications, and the note’s implications

🚨 FIVE MISSED CALLS. A locked hotel room. And a horrifying 45-minute gap that sealed their fate… 11-year-old cheer star…

The competitive cheer world — with its demanding schedules, travel, and performance expectations — has been highlighted in discussions around the case

😱 CHILLING WITNESS ACCOUNT: “I heard them screaming at 7 AM.” — A hotel guest right next door at the…

End of content

No more pages to load