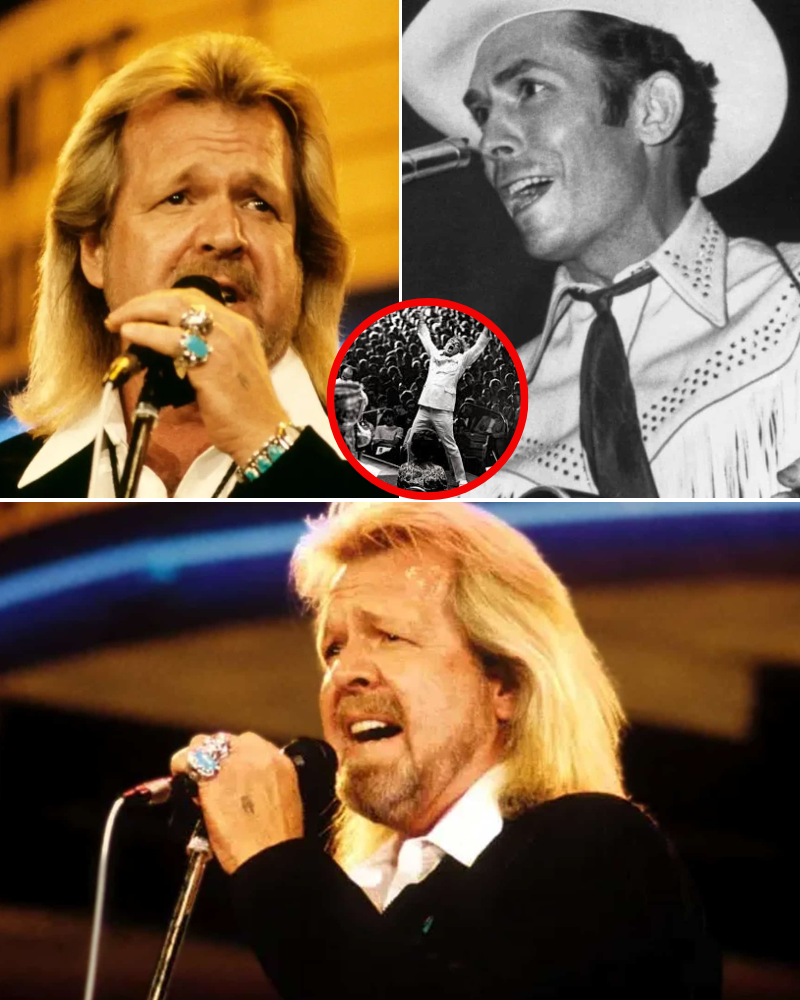

Country music in the 1980s was a wild ride of big hair, bigger hooks, and beer-soaked anthems that had folks two-stepping till closing time. At the heart of that honky-tonk hurricane was Mel McDaniel, the Oklahoma-born crooner whose “Baby’s Got Her Blue Jeans On” turned jukeboxes into gold mines and earned him a spot in the Grand Ole Opry hall of fame. But one fateful night in 1996, a simple misstep into an unseen pit turned the road warrior’s world upside down – ending his touring days for good and sparking a bitter legal battle that dragged on for years.

It was November 13, 1996, at the Heymann Performing Arts Center in Lafayette, Louisiana. McDaniel, then 54 and still slinging his signature upbeat country with the energy of a man half his age, was in the middle of a crowd-pleasing set. Known for his crowd work – handing out guitar picks, shaking hands, and pulling fans into the fun – he sauntered toward the edge of the stage like he had a thousand times before. The lights were low, the applause was roaring, and the Oklahoma native figured he was stepping into another rowdy auditorium full of Saturday-night sinners.

What he didn’t know was that beyond the footlights lurked a seven-foot-deep orchestra pit, unmarked and uncovered. No warning signs. No barriers. Just a black hole waiting to swallow him whole. “I could not see anything,” McDaniel would recall years later in a deposition that read like a bad dream. “I thought it was like an auditorium or something. I did not think about there being a hole there at all. I took about four steps and down I went.”

The fall was brutal. McDaniel plummeted headfirst, shattering bones in his legs, pelvis, and spine. Internal bleeding followed, along with a cascade of surgeries that would stretch over a decade. He spent months in rehab, relearning how to walk – a cane becoming his reluctant sidekick for the rest of his days. Doctors called it a miracle he walked at all; friends called it the end of an era.

McDaniel wasn’t just any road dog. Born September 6, 1942, in the dusty plains of Checotah, Oklahoma, he caught the music bug young, mesmerized by Elvis on the black-and-white TV. By 15, he was strumming his self-taught guitar at high school talent shows, then hustling gigs in Tulsa’s dive bars and even oil-field joints in Alaska. Nashville called in the ’70s, and after scraping by, he inked a deal with Capitol Records in 1976. The payoff hit like a freight train in 1981 with “Louisiana Saturday Night,” a Bob McDill-penned toe-tapper that peaked at No. 7 and painted him as the king of feel-good country.

The ’80s were his golden decade. Tracks like “Take Me to the Country,” “Big Ole Brew,” and “I Call It Love” kept the hits rolling, but it was “Baby’s Got Her Blue Jeans On” in 1984 that cemented his legend. The cheeky, foot-stomping single shot to No. 1, snagged Grammy and CMA nods, and became an instant barroom staple. Critics called it lightweight; fans called it lightning in a bottle. McDaniel didn’t care – he was too busy packing houses and joining the Grand Ole Opry in 1986, where his old-school charm and gravelly twang made him a fixture for decades.

By 1996, the hits had slowed – his last big studio swing was the 1991 album Country Pride – but McDaniel was still a touring beast. He lived for the stage, the sweat, the shared beers with strangers turned friends. That night in Lafayette was supposed to be just another high-octane stop on the circuit. Instead, it was the plunge that clipped his wings.

The aftermath was a nightmare of pain pills, physical therapy, and mounting bills. McDaniel’s doctors warned him: no more buses, no more 200-date marathons. The man who once leaped across stages like a caffeinated cowboy was grounded, reduced to occasional Opry spots and local gigs he could drive to. “It broke my heart more than my bones,” he told a reporter in 2000, his voice thick with the regret of a performer robbed of his pulpit. Fans mourned the loss; the industry whispered about a has-been. But McDaniel fought back – not just with grit, but with lawyers.

What followed was a David-vs.-Goliath lawsuit that exposed the ugly underbelly of venue safety. McDaniel sued the City of Lafayette (owners of the Heymann Center), the event promoter, and the Carencro Lions Club (who co-sponsored the show). Court docs revealed a horror show: between 1983 and 1998, nine people had tumbled into that same unguarded pit, including one fatal fall. The venue had a safety cover available – a cheap metal grate that cost peanuts to rent – but the promoter skipped it to save a few bucks. “It was negligence, plain and simple,” McDaniel’s attorney argued in filings. “A performer gives his all up there, and this is how they’re repaid?”

The case dragged like a bad hangover, bouncing through appeals for nearly a decade. McDaniel testified in depositions, limping to the stand on his cane, recounting the terror of the drop and the lifetime of pain. Witnesses from the show backed him up: the lighting was a blackout beyond the stage edge, a setup begging for disaster. Finally, in the mid-2000s, a jury sided with him, awarding damages to cover medical costs, lost wages, and suffering. The exact figure stayed sealed, but insiders pegged it in the high six figures – a bittersweet payday for a man who’d trade it all for one more sold-out night.

Even hobbled, McDaniel didn’t fade quietly. He scratched out a 2006 comeback album, Reloaded: Tried, True and New, dusting off old hits with fresh fire. His last Opry hurrah came in 2009, sharing the stage with Jimmy Dickens, George Hamilton IV, and The Whites – a who’s-who of country elders toasting the good old days. But weeks later, a massive heart attack sidelined him again, landing him in a medically induced coma. He clawed back from that too, only to face stage 3b lung cancer in 2011. Defiant to the end, he cut his swan song, The Last Ride, from a hospital bed. Mel McDaniel died on March 31, 2011, at 68 – a fighter who went down swinging.

Today, as country evolves with slick producers and TikTok twang, McDaniel’s story hits like a cautionary chord. His music endures – “Louisiana Saturday Night” still blasts from tailgates, “Baby’s Got Her Blue Jeans On” from wedding dances. But the accident lingers as a stark reminder: the road to glory is littered with pitfalls, literal and otherwise. Venues have tightened safety nets since, with barriers and covers now standard. Promoters think twice about cutting corners.

For McDaniel’s family and fans, it’s more personal. “He was the heartbeat of those Saturday nights,” says his daughter, Trisa McDaniel, in a recent Opry tribute. “That fall took the stage from him, but not the song from his soul.” And in Nashville’s circles, whispers tie it back to the outlaw spirit – the same raw edge that fueled Waylon Jennings’ rebellion. McDaniel wasn’t flipping off Music Row, but his lawsuit was a middle finger to carelessness, proving even the upbeat boys can draw a line in the sawdust.

Nearly three decades on, Mel McDaniel’s plunge remains a gut-punch tale: how one unseen drop silenced the cheers, but couldn’t dim the echo of a voice that made blue jeans and brews feel like poetry. Country lost a road king that night, but gained a legend who taught ’em – watch your step out there. The music plays on, cane or no cane.

News

JonBenét Ramsey Murder: Boulder Police Confirm New Evidence and Renewed DNA Testing Nearly 29 Years Later

Nearly three decades after the murder of six-year-old JonBenét Ramsey, authorities in Colorado are confirming something many believed might never…

Late Night’s “Freedom Show”: Why Colbert, Kimmel, and Fallon Are Rewriting Television in 2026

Late-night television is on the verge of a fundamental shift. According to industry insiders, The Late Show with Stephen Colbert,…

JonBenét Ramsey: The 911 Call That Didn’t End — and the Audio That Changed the Case Forever

On December 26th, 1996, at exactly 5:52 AM, Patsy Ramsey dialed 911 from her home in Boulder, Colorado. Her voice…

RCMP Confirms Daniel Martell’s Midnight Trip Holds a Crucial Clue in the Disappearance of Lily and Jack Sullivan

At exactly 11:47 PM on May 1st, 2025, a grainy security camera at a remote gas station quietly recorded what…

“Wake Up, We Need 100,000 Francs”: How an Obsession With Revenue Preceded the Crans-Montana Fire

“Wake up. We need 100,000 francs.” According to investigators and testimony cited in Italian media, that sentence captures the mindset…

After Winning Three Awards, Cardi B Chose McDonald’s — and the Moment Spoke Louder Than the Trophies

In an industry built on excess, luxury, and carefully curated images, moments of simplicity often stand out the most. One…

End of content

No more pages to load