In the heartland haze of Vandalia, Illinois—a fading frontier town where cornstalks whisper secrets to the wind and front porches host Sunday suppers under sagging awnings—the illusion of safety shattered like fragile glass on November 14, 2025. It was here, in a backyard cluttered with the relics of rural life—a rusted swing set, overgrown weeds, and a weathered RV that squatted like an unwelcome guest—that 14-year-old Kylie Toberman met her end. Not at the hands of a stranger lurking in the shadows, but from the grip of someone she called family: her step-uncle, Arnold Barry Rivera Jr., a 43-year-old man whose blood ties masked a history of predation. Strangled with jumper cables after a brutal sexual assault, Kylie’s body was crammed into a plastic tote inside the very RV where Rivera lived, just steps from the home she shared with her adoptive mother and two young sisters. As the news rippled through Vandalia’s 7,000 souls and beyond, it ignited a primal fear in parents nationwide: when the monster wears the face of kin, how do we protect our teenagers from the wolves within?

Kylie’s story is one of fleeting joys snatched away too soon, a testament to the resilience of a girl who wrestled not just opponents on the mat, but the chaos of her own fractured beginnings. Born into the quiet struggles of Effingham County, about an hour’s drive east of Vandalia, she entered the world amid whispers of instability. Her biological mother, Megan Zeller, a woman weathered by life’s relentless storms, made the agonizing choice over five years ago to place Kylie and her two younger sisters up for adoption. It wasn’t a relinquishment of love, Zeller would later explain in tear-streaked Facebook posts that pierced the veil of her private pain, but a desperate grasp for the stability she couldn’t provide. “I was young and dumb… I thought I could trust somebody, and now my baby is an angel,” she wrote, her words a raw mosaic of regret and rage. Kylie’s father had succumbed to a drug overdose years earlier, leaving behind a void that no child should inherit. Placed with the Toberman family through a tangled web of extended kin, Kylie found a patchwork haven in Vandalia—a modest ranch house on West Gallatin Street, its white siding peeling like old promises, encircled by a chain-link fence that now feels like a mocking barrier.

Life in the Toberman home wasn’t picture-perfect, but Kylie infused it with her irrepressible spark. At 5-foot-2 and a wiry 110 pounds, she was a force on the wrestling mats at Vandalia Junior High, where she’d joined the Vandal Wrestling Takedown Club just months before her death. Coaches marveled at her tenacity; she wasn’t the biggest, but she pinned with a ferocity born of quiet determination, earning the “most improved wrestler” accolade that hung like a badge of pride in her bedroom. Off the mat, Kylie was a whirlwind of sass and sweetness—braiding her sisters’ hair into elaborate French twists, sneaking kibble to the stray cats that prowled the neighborhood, and belting out Taylor Swift anthems in the backyard until dusk painted the sky pink. Her grandmothers, Leann Deweese and Lisa Richards, cherished her from afar, their visits sporadic due to the adoption’s legal knots. “Very beautiful, very energetic, very happy all the time,” Deweese, a retired nurse with callused hands from years of bedside vigils, recalled in a voice choked by sobs. Richards, who made the grueling drive from across the state for Rivera’s arraignment, added, “She was our light, even if we couldn’t hold it as often as we wanted.” School friends like Caitlyn Shellenbarger remembered sleepovers alive with TikTok dances and dreams of veterinary school, where Kylie plotted to save every abandoned pup in Fayette County. In a town where Friday nights meant football under floodlights and summers meant county fairs, Kylie embodied the unyielding optimism of Midwestern youth—untarnished, until the family she trusted turned toxic.

Arnold Rivera wasn’t an outsider; he was woven into the fabric of Kylie’s world, a thread frayed by secrets long ignored. Known to some as “Bubba,” the 43-year-old positioned himself as the family’s unofficial handyman, tinkering with leaky faucets and overgrown lawns when the adoptive mother’s double shifts at the local grain processor left gaps. Legally, he was an adoptive brother to Kylie’s guardian through the Tobermans’ labyrinthine kinship; informally, a step-uncle via faded marital ties that bound him to the periphery. His RV, a 1980s relic with faded blue siding and a door that creaked like a warning, parked like a sentinel behind the house—a place the girls sometimes crashed to escape the chaos inside. Locals whispered about Rivera’s main dwelling: a hoarder’s den overrun with barking dogs and the stench of neglect, floors slick with feces and clutter that swallowed furniture whole. “The girls wouldn’t stay there,” one neighbor confided, shaking her head at the memory. “That RV was supposed to be safer.” Rivera watched the children, ran errands, even drove them to practice—acts of “help” that blinded the family to the rot beneath. But his past was a siren song of danger, a criminal ledger spanning 25 years that screamed for scrutiny it never received.

It started in 2000, in the dim courtrooms of Macon County, when a 20-year-old Rivera faced felonies that should have sealed his fate: burglary, for ransacking a Decatur home under cover of night, and criminal sexual abuse of a child aged 9 to 16—a violation that now eerily mirrors the horrors inflicted on Kylie. Prosecutors, in a plea bargain that reeks of corner-cutting justice, dropped both charges for a guilty plea to aggravated battery in a public melee. Thirty months of probation followed, a gossamer restraint that dissolved by 2003, leaving him free to prowl. The pattern persisted: 2008 brought possession of a stolen vehicle, another 24 months of oversight ending in March 2023. Whispers from old haunts painted him as a powder keg—bar brawls in smoky Decatur taverns, road-rage flare-ups that escalated to drawn knives, a temper that simmered just below civility. Yet, in Vandalia’s culture of communal forgiveness, where kin sticks no matter the stains, Rivera evaded the registry that might have flagged him as a predator. No mandatory therapy, no barred proximity to minors. He was family, after all—and family, in the heartland’s creed, gets the benefit of the doubt. Until that doubt became a death sentence.

The nightmare unfurled on a Thursday evening unremarkable in its ordinariness. Kylie, fresh from wrestling drills where she’d nailed a textbook double-leg takedown, devoured spaghetti at the kitchen table, her laughter cutting through a sibling spat over the last meatball. Last seen around 9 p.m. in a red sweatshirt and black leggings—outfit that would haunt search posters—she vanished into the night. Perhaps a late errand, a text-fueled wander to a friend’s porch? By 6:32 a.m. the next day, the adoptive mother, her voice a razor of panic, rang Vandalia Police. An alert blasted across social media: Kylie’s school portrait, hazel eyes sparkling with mischief, flanked by desperate pleas. The town surged into action—mechanics like Scott Hull marshaled their teens to scour ditches and creek beds, flashlights carving paths through the November fog. “This is our safe haven,” Hull lamented later, his grease-blackened hands clenched. “Kids roam free. You don’t brace for the betrayal next door.” Tips mounted: a relative’s gnawing suspicion over Rivera’s dawn evasion, his padlocked RV door a glaring anomaly. Echoes of prior DCFS complaints—multiple since January, decrying his “erratic” glares and outbursts—faded into bureaucratic fog. “They were called several times from several people, and they didn’t do anything,” Deweese fumed, her composure splintering.

By 2 p.m., as a weak sun mocked the chill, officers zeroed in on the RV. Bolt cutters sheared the chain with a screech that hung in the air like a dirge. Inside, the fetor of stale beer and despair assaulted them: cans strewn like casings from a firefight, wrappers crusting counters in greasy decay. Then, the tote—blue plastic, duct-taped lid flaking like scabbed skin—shoved under a bench. Pried open, it revealed Kylie: curled fetal, skin mottled with bruises that flowered across her throat and thighs, ligature welts from the jumper cables coiled nearby like a viper’s shed skin. Signs of the assault screamed from her form—savage, intimate, unforgivable. No pulse, only the echo of what was stolen. Responders reeled; one trooper’s whispered “Oh God” dissolved into radio static as forensics descended in white suits, cataloging the cables’ black coils slick with finality. Outside, the search dissolved into wails—mothers yanking children indoors, fathers roaring at the sky.

Rivera fled, a specter in gray hoodie, snared by 5 p.m. at a Decatur truck stop, cuffs clicking on trembling wrists. Arraigned November 17 in Fayette County’s austere courthouse, he stood hollow-eyed under harsh lights, Richards’ glare boring into him like judgment day. Charging sheets spilled the indictment: first-degree murder, the assault a lured trap into the RV’s maw, the strangling a rage-fueled crescendo, the concealment a craven veil. A pre-dawn social media post from his phone—cryptic barbs hinting premeditation—now fuels the probe. Zeller, Kylie’s bio mom, unleashed her fury online: “The past few days have been unimaginably hard. We’re supporting her sisters and preparing for court. She didn’t deserve this.” Shellenbarger, clutching a sleepover snapshot, seethed, “He was a disgusting man. She was failed.”

Vandalia, that cradle of pioneer grit, convulses in grief. Pink ribbons—Kylie’s battle color—fringe Gallatin’s lamps, plush toys mound at the station like talismans. Junior High halls drowned in pink Monday, counselors from Effingham bolstering the breach. The wrestling club mourned: “Our team and community are grieving the loss of such a sweet and bright young girl.” Vigils flicker at the chapel, singlets standing sentinel amid sobs and stories of her fire. But fury simmers beneath: at Rivera, the kin who cloaked his claws; at DCFS, whose alerts evaporated like mist; at a justice system that bartered child-abuse charges for battery pleas, unleashing a repeat offender on vulnerable teens.

This betrayal cuts deepest because it’s familial—a violation of the sacred trust that should shield our children. Nationwide, parents clutch teens closer, replaying Kylie’s fate like a cautionary reel: How many “uncles” harbor histories we ignore? Statistics whisper grim truths—family members perpetrate over 90% of child sexual assaults, per advocacy tallies, yet rural outposts like Fayette strain under caseloads that bury warnings. Illinois’ apprehension rates for at-risk youth lag, cultural blind spots amplifying the peril for blended families like the Tobermans’. Zeller vows crusade: “I will not stop until my child gets justice,” her posts a beacon for reform—mandatory kin checks, DCFS audits, registries that stick like burrs.

As November’s gales strip Vandalia’s oaks bare, Kylie’s void aches like an open wound. Her service looms, a tapestry of tributes: mat-side pins, kitten rescues, Swift-sung dreams. Richards, courthouse tears drying to resolve, pledges, “We’ll make her story change things.” In this heartland hamlet, scarred yet steadfast, the fight endures—not for vengeance, but vigilance. For Kylie, the grappler who twisted fate till the end, her legacy demands we question every embrace: In the circle of family, who watches the shadows? How many more teens must fall before we fortify the home front? The answer, parents whisper in the dark, starts with us—eyes wide, instincts sharp, trust earned, not assumed. In honoring Kylie, we armor the innocent, one wary glance at a time.

News

“She Was Just a Poet, a Mother, and a Wife… Then an ICE Agent Shot and Killed Her Right on Her Street”: The Shocking Death of Renée Nicole Good – What Really Happened Hours After Dropping Her Children Off at School

On the morning of January 7, 2026, Renée Nicole Good, a 37-year-old U.S. citizen, poet, writer, and devoted mother of…

NEW VIDEO EMERGES: Chilling Footage Reveals Renee Good’s Final Moments Before Fatal ICE Shooting – Her Last Words Expose a Desperate Plea as Bullets Fly

The release of new cellphone footage has intensified the national outcry over the fatal shooting of 37-year-old Renee Nicole Good…

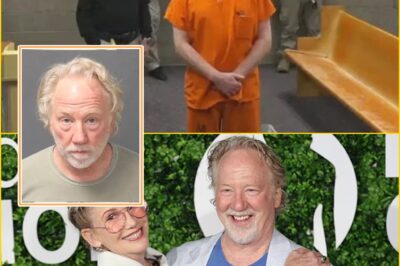

“Your Hands Used for Saving People, Not Killing Them”: Judge’s Stark Words Leave Accused Surgeon Michael David McKee Collapsing in Court During First Hearing in Tepe Double Murder Case

The Franklin County courtroom in Columbus, Ohio, fell into stunned silence on January 14, 2026, as Judge Elena Ramirez delivered…

“This is Not How It Was Supposed to End”: Timothy Busfield’s Grave Court Appearance as Judge Denies Bail in Shocking Child Sex Abuse Case

In a courtroom moment that stunned observers and sent ripples through Hollywood and beyond, veteran actor and director Timothy Busfield,…

Husband of Chicago Teacher Linda Brown Discovers Heartbreaking Suicide Note Revealing Her Final Reasons for Leaving and Ending Her Life

The tragic death of Linda Brown, the 53-year-old special education teacher at Robert Healy Elementary School in Chicago, has taken…

“She Escaped the Fire… Then Turned Back”: The 18-Year-Old Hero Who Ran into the Flames at Crans-Montana — and Is Now Fighting for Her Life

In the chaos of the deadly New Year’s Eve fire at Le Constellation bar in the Swiss ski resort of…

End of content

No more pages to load