The dense, fog-shrouded woods along Gairloch Road, where the East River’s sluggish current carves a secretive path through Pictou County’s rural heartland, have long been a place of whispered legends and quiet reflection. But on the crisp morning of November 12, 2025, those woods became the stage for a discovery that shattered six months of anguished silence and reignited hope – and horror – in the desperate search for missing siblings Jack and Lilly Sullivan. A team of local volunteers, combing the riverbank’s tangled underbrush with metal detectors and a renewed sense of urgency, unearthed a small, mud-caked child’s boot – size 11, pink with cartoon butterflies, unmistakably Lilly’s – half-buried in the soft loam just 200 meters from the family’s remote home. Mere feet away, snagged on a thornbush, lay a frayed pink sock embroidered with “L.S.,” its threads torn as if by frantic fingers or rushing water. The finds, confirmed by RCMP forensics later that day, mark the first physical evidence in the baffling case of the 4-year-old Jack and 6-year-old Lilly, who vanished without a trace from their Lansdowne Station residence on May 2, 2025. As the Royal Canadian Mounted Police escalate their “intensive investigative approach,” the Buzzard family’s long vigil edges closer to answers – or an agonizing abyss. “It’s our girl – no doubt,” said stepgrandmother Janie MacKenzie, her voice breaking as she clutched a photo of Lilly’s beaming face at a family picnic. “But how? Why there? We’re one step from hope or heartbreak.” In a community gripped by grief and a nation haunted by the unknown, this riverbank revelation isn’t just a clue; it’s a clarion call, pulling the Sullivan saga from cold case shadows into the stark light of potential tragedy.

The discovery dawned like a reluctant dawn, the volunteer team’s efforts a testament to the unyielding spirit of a rural Nova Scotia hamlet that has refused to let its youngest vanish into oblivion. It was 9:15 a.m. when Cheryl Robinson, a 52-year-old retired nurse and family friend who has walked every inch of those woods since May, spotted the boot’s telltale pink flash amid a snarl of brambles near a bend where the East River eddies lazily against granite outcrops. “I was poking with my stick – same one I’ve used since day one – when it glinted,” Robinson recounted in a trembling interview at the New Glasgow RCMP detachment later that afternoon, her hands still caked with river mud. “Pulled it free, and my heart stopped – those butterflies, Lilly’s favorite from Walmart last Christmas. Then the sock, caught like it was waiting.” The team – a dozen locals led by Haley Ferdinand, Lilly and Jack’s aunt and a vocal fixture in the #FindTheSullivans campaign – radioed the find immediately, halting their sweep as RCMP officers cordoned the site with yellow tape that fluttered like fallen leaves. Forensics arrived within 20 minutes: Santa Claus-sized Santa Clauses from Halifax’s Major Crime Unit, their kits gleaming with gadgets for DNA drags and fiber forensics. Preliminary tests – soil samples matching the Buzzard backyard, fibers tracing to Lilly’s last-worn pajamas – confirmed the connection by noon, the boot’s size 11 tread (marked “29” on the sole) aligning with March Walmart receipts from Malehya Brooks-Murray, the children’s mother.

Lilly Rose Sullivan and her brother Jack Thomas Sullivan were the picture of rural innocence – a curly-haired 6-year-old with a gap-toothed grin and a love for pirate tales, and her 4-year-old shadow, a towheaded tyke with a thumb-sucking habit and a penchant for fire trucks. Living with their mother Malehya Brooks-Murray, 32, stepfather Daniel Robert Martell, 35, and half-sister Ava, 1, in a weathered double-wide on Gairloch Road – a gravel ribbon flanked by fir forests and the East River’s moody meanders – the siblings were the heartbeat of Lansdowne Station, a dot of 200 souls where the closest grocery is a 15-minute drive to New Glasgow. Last seen on May 1 at 2:25 p.m. in a Dollarama surveillance clip – Lilly clutching a stuffed unicorn, Jack waving a toy hammer – the pair were kept home from Salt Springs Elementary the next day for “coughs,” per Brooks-Murray’s report. At 10 a.m. May 2, she called 911: “The kids are gone – I woke up, and they’re not here.” An Amber Alert never issued – RCMP citing “no evidence of abduction” – the search swelled to 500 volunteers, helicopters humming over hemlocks, divers dragging the river’s depths. Six months on, with over 700 tips tallied and polygraphs passed by parents and kin, the case had cooled to embers – until the boot’s burial unearthed a blaze.

The Buzzard family’s fracture predates the find, a fault line fissured by foster falls and fractured fealties. Malehya Brooks-Murray, a 32-year-old cashier at New Glasgow’s Sobeys with a history of housing hops and health hurdles, met Daniel Martell, a 35-year-old millwright with a steady job at the local pulp plant, in 2020 amid pandemic pivots. Blended from Brooks-Murray’s prior union with Cody Sullivan – the biological father estranged since 2021 after a custody clash over “unfit parenting” – the household housed hope amid hardship: Lilly’s kindergarten chatter, Jack’s truck-toy tantrums, Ava’s gummy grins. But cracks crept: Brooks-Murray’s March 2025 Walmart boot buy for Lilly, captured on banking records, coincided with CPS check-ins for “chronic coughs” masking malnutrition concerns. Sullivan, the sidelined sire in Middle Musquodoboit, passed a June 12 polygraph “truthful” on “haven’t seen the kids in three years,” his appeals for access rebuffed by Brooks-Murray’s “toxic ties” texts. Martell’s June 10 test? “Inconclusive” per documents, his “physiology unsuitable” a red flag in redacted warrants. The riverbank relics – boot and sock – now knot the narrative: “Lilly’s last steps?” Ferdinand frets, her auntly ache amplified in a November 13 presser.

The RCMP’s reckoning, a royal rumble in rural repose, ramps with the relics. Led by Staff Sergeant Curtis MacKinnon, Pictou District’s commander whose 25-year tenure tallies triumphs from Halifax homicides to Hants County hauntings, the Major Crime Unit mobilizes: forensics fingerprint the find for familial fibers, divers dredge downstream for “downward drifts,” drones drone the dense canopy for canopy clues. “This is a pivotal piece – physical proof in a puzzle of possibilities,” MacKinnon stated November 12 at New Glasgow barracks, his Mountie mustache masking measured might. Warrants, redacted in August releases, reveal ripples: Brooks-Murray’s banking blips to a Barstow burner, Martell’s motel musts in Moncton, a pink blanket’s pink shreds in trash – Lilly’s, per family fiat. Polygraphs pile: grandmother Cyndy Brooks-Murray and beau Wade Paris “passed,” stepgrandma Janie MacKenzie “unsuitable.” Tips tally 750, from Utah U-Haul hunches to Nebraska needle pricks. “Wandered away?” the initial “no foul play” fiat fades; “familial fracture?” festers in files.

Lansdowne Station, a Pictou pinprick of 200 where school buses rumble like reluctant rhinos and Friday fish fries forge family, frays under the find. The Gairloch home, a double-wide draped in yellow tape since May 3, draws daily dawdlers: teal lanterns lit at dusk (Lilly’s hue), neighbors nailing “Find the Sullivans” flyers to fir trunks. Salt Springs Elementary’s assembly on November 13 swells with 200 – pom-poms piled at the podium, a cheer routine replayed on the gym floor, Jack’s toy hammer hammered into a memorial marker. “Lilly was our light – curly chaos in corridors,” principal Dr. Marcus Hale homilized, 300 locals linking arms in silent solidarity. Her TikTok trove, a 5K-follower feed of flips and family frolics, now nectar of nostalgia: last loop, May 1 from Dollarama, lip-syncing “Ocean Eyes” in teal, captioned “School skip day – unicorn hunt! 🦄.” Friends flock, comments cascade: “Shine on, Lilly – our unbreakable.”

The Buzzard brood’s blended bonds buckle: Brooks-Murray, 32 and Sobeys scribe whose spreadsheets steadied storms, supplements sorrow in seclusion – her March Walmart boot buy a beacon in banking blips. Martell, 35 and millwright might, mans the mantle: “Jack’s trucks, Lilly’s laughs – our home’s hollow without ’em.” Sullivan, sidelined sire in Musquodoboit, surges support: “My babies – biological bond unbreakable. This boot? It’s a breadcrumb home.” The maternal matriarchs – Cyndy and Janie – jaw in joint juntas, their polygraph passes a paltry palliative.

As November’s night deepens and the East River eddies eternal, the Sullivans’ saga simmers: clarion for candor in courtroom corridors, cry for closure in conspiracy confines. Lilly’s legacy? Luminous – beacon for backroad believers, ballad for bereft. The boot’s burial births hope or horror – a 6-year-old’s step from the riverbank, a family’s fight for fractured facts. In their ache, a province’s awakening – to the peril of pauses without pursuit, the poison of plots without pity.

News

“She Was Just a Poet, a Mother, and a Wife… Then an ICE Agent Shot and Killed Her Right on Her Street”: The Shocking Death of Renée Nicole Good – What Really Happened Hours After Dropping Her Children Off at School

On the morning of January 7, 2026, Renée Nicole Good, a 37-year-old U.S. citizen, poet, writer, and devoted mother of…

NEW VIDEO EMERGES: Chilling Footage Reveals Renee Good’s Final Moments Before Fatal ICE Shooting – Her Last Words Expose a Desperate Plea as Bullets Fly

The release of new cellphone footage has intensified the national outcry over the fatal shooting of 37-year-old Renee Nicole Good…

“Your Hands Used for Saving People, Not Killing Them”: Judge’s Stark Words Leave Accused Surgeon Michael David McKee Collapsing in Court During First Hearing in Tepe Double Murder Case

The Franklin County courtroom in Columbus, Ohio, fell into stunned silence on January 14, 2026, as Judge Elena Ramirez delivered…

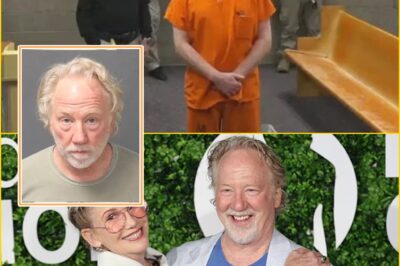

“This is Not How It Was Supposed to End”: Timothy Busfield’s Grave Court Appearance as Judge Denies Bail in Shocking Child Sex Abuse Case

In a courtroom moment that stunned observers and sent ripples through Hollywood and beyond, veteran actor and director Timothy Busfield,…

Husband of Chicago Teacher Linda Brown Discovers Heartbreaking Suicide Note Revealing Her Final Reasons for Leaving and Ending Her Life

The tragic death of Linda Brown, the 53-year-old special education teacher at Robert Healy Elementary School in Chicago, has taken…

“She Escaped the Fire… Then Turned Back”: The 18-Year-Old Hero Who Ran into the Flames at Crans-Montana — and Is Now Fighting for Her Life

In the chaos of the deadly New Year’s Eve fire at Le Constellation bar in the Swiss ski resort of…

End of content

No more pages to load