In a bombshell that’s ripped the scab off one of Britain’s most infamous gangland executions three decades after the blood-soaked Range Rover became a symbol of Essex’s cocaine cowboys, a secret 2015 audio tape has emerged capturing the late John Whomes – brother of convicted killer Jack – confessing to nobbling a key prosecution witness mid-trial, admitting he phoned the man from a public booth outside Essex Police HQ and begged him to “switch” his evidence in the witness box to sabotage the case against his sibling. “I rung him… told him what to say, and he done it… it f***ing worked in our favour,” John slurs on the clandestine recording, obtained by The Sun during the filming of the 2015 documentary Essex Boys: The Truth. The revelation – surfacing on the 30th anniversary of the Rettendon murders that claimed three lives in a pump-action shotgun ambush – has torpedoed the two-decade innocence crusade for Jack Whomes and Mick “The Angel of Death” Steele, both now free on parole but forever branded as the triggermen in a drug feud that inspired Hollywood horrors. “This places clarity around exactly what happened,” thunders retired Essex detective Paul Maleary. “After 30 years of debate, it’s time to accept the right men were convicted.” As the Criminal Cases Review Commission pores over the tape amid fresh calls to slam the door on appeals, one damning question echoes over the misty lanes of Rettendon: was the Essex Boys saga a miscarriage of justice… or a masterclass in manipulation?

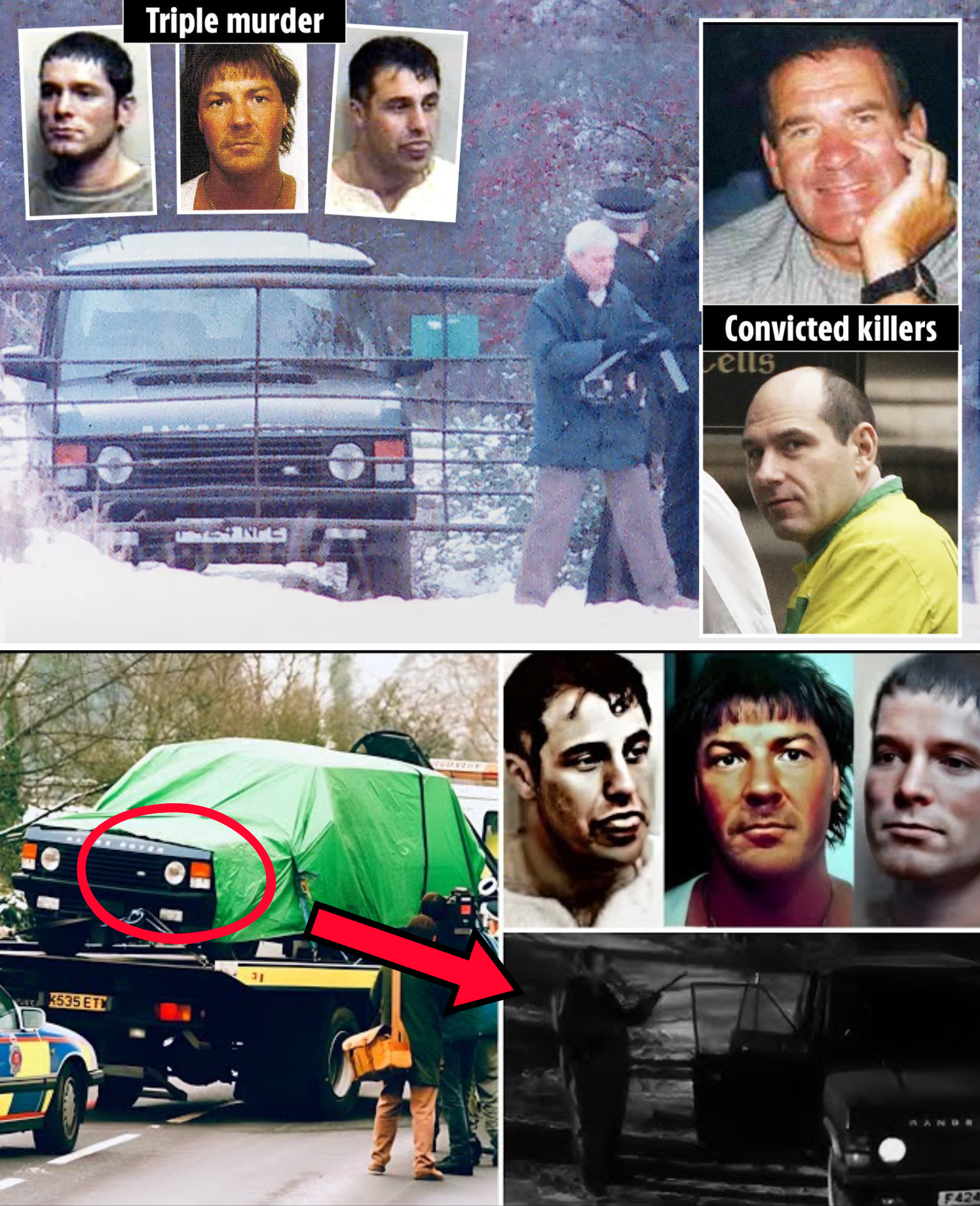

The nightmare ignited on a frostbitten December 6, 1995, when a farmer’s Land Rover headlights pierced the predawn gloom of Workhouse Lane, illuminating a metallic blue Range Rover marooned in a muddy ditch, its windscreen a spiderweb of bullet holes and its interior a slaughterhouse tableau. Slumped in the front passenger seat: Patrick “Pat” Tate, 37, the roided-up enforcer whose steroid-fueled rages had terrorized dealers from Basildon to Braintree. Driver’s side: Tony Tucker, 38, the doorman-turned-doomsday dealer whose security firm masked a multimillion-pound coke empire. Boot? Craig Rolfe, 26, the junkie sidekick whose veins were as mapped as the M25. All three riddled with shotgun blasts at point-blank range – Tate taking six to the chest, Tucker five, Rolfe a face full of No. 4 shot. “It was like a scene from a Tarantino flick – but real, and raw,” recalls the farmer, Matthew Fleming, now 72, his voice still quavering 30 years on. The trio had been lured to the lane under the pretense of a £100,000 cannabis handover, only to meet muzzles from the shadows. Within hours, Essex Police’s murder squad swarmed, unearthing a web of betrayal woven from Amsterdam’s skunk farms to Southend’s snooker halls – a feud fueled by a botched £60,000 shipment where Tate and Tucker allegedly stiffed supplier Mick Steele on a refund.

Five months of manhunts led to the Old Bailey in January 1998, where supergrass Darren “Mr. Big” Nicholls – a twitchy getaway driver with a penchant for police payoffs – turned state’s evidence, fingering Whomes and Steele as the shotgun assassins. Nicholls claimed he ferried Whomes to the lane in his BMW, watched Steele arrive with the victims in the Range Rover, heard the blasts echo like thunderclaps, then scooped the killers post-pop-pop. Cell-site data pinned the phones, tyre tracks matched Nicholls’ motor – and the jury bought it hook, line, and sawn-off. Whomes, a 22-year-old farmhand from Rayleigh, drew 21.5 years; Steele, the 35-year-old Colchester kingpin with a rap sheet longer than the A13, copped 23. “They’re monsters – cold-blooded killers who thought they were untouchable,” thundered prosecutor Victor Temple QC as the gavel fell. But from the cells, the innocence orchestra swelled: Whomes and Steele screamed “fit-up,” Nicholls a “lying weasel” greased by corrupt copper DC Derek Marsden. Appeals crashed in 2006 and 2010, the Court of Appeal dubbing Nicholls’ handler ties “unsavory” but his evidence “overwhelming.”

Enter John Whomes, Jack’s bulldog brother and the campaign’s bulldozer – a relentless rallyist who stormed the Royal Courts of Justice with banners screaming “Free the Rettendon Three!” and petitions amassing 500,000 signatures. For 22 years, he hawked the “supergrass stitch-up” narrative, rubbing shoulders with celebs like Ray Winstone and penning pamplets that painted Nicholls as the real Ripper. But in a smoky bar during the 2015 doc shoot, fate flipped the script: Bernard O’Mahoney – the ex-Essex Boy turned true-crime scribe who’d chronicled the clan in his 1997 tome Essex Boys – wired John for a boozy chinwag. What spilled? A sloshed soliloquy of sabotage. “The evidence he give wasn’t the right evidence… I asked him to [switch],” John boasted of witness Barry Dorman, the car dealer and ex-Met copper who’d flogged the murder Rover to Tate’s crew. Dorman, John confessed, was primed to torpedo the trial with tales of Steele’s “friendly” Ostend meet-up, but John – mid-trial, from a phone box yards from HQ – begged a U-turn: “I told him what to say, and he done it… risky, but it f***ing worked.” Dorman, per the tape, flipped in the box – omitting the Ostend olive branch, letting Nicholls’ narrative stick like glue. Dorman, who croaked in 2021 at 73, had denied grudge-holding; now, the recording recasts him as a reluctant rook in John’s chess game.

The tape’s timing? Torturously tantalizing. John’s confession dropped during The Truth’s edit, but O’Mahoney – haunted by his own Essex ghosts – shelved it, fearing a family feud flare-up. “Bernard suggested we mic him up… it was raw, real,” recalls director Chris Matthews, 58, who unearthed the audio last month amid anniversary angst. John’s November 2024 death from bowel cancer at 60 – after a final plea to Shabana Mahmood to free Steele – unlocked the lid. Now, private eyes from Retrial Advocacy have lobbed it to the CCRC, arguing the perjury poisons the pot: if Dorman was nobbled, was Nicholls next? “This isn’t hearsay – it’s hard proof of tampering,” thunders Matthews. “Thirty years on, the case refuses to die because the truth’s been twisted like a shotgun barrel.” Whomes, 49 and paroled in 2021, tinkers with motors in Suffolk, insisting “John was drunk, delusional – we’re innocent.” Steele, 60 and frail, holes up in a Colchester care home, his June release a pyrrhic pardon: “The system screwed us – now it’s screwing itself.”

The reverberations? A seismic shift in a saga that’s spawned six Rise of the Footsoldier flicks and a Netflix nod in The Capture’s conspiracy coils. Essex Police, stung by Marsden’s 2002 jailing, stonewalls: “Historical, handled.” But campaign corpse John’s kin? Cracking: niece Danielle Whomes, 28, blasts the tape as “vindictive vengeance” from O’Mahoney, the “snitch who switched sides.” Nicholls? Vanished into witness protection, his £100k payout a punchline. Leah Betts? The 18-year-old ecstasy casualty whose 1995 death turbocharged the tabloid terror – her dad Paul’s face on billboards screaming “Just Say No” – lingers as the Essex epitaph, a cautionary corpse in the coke cowboys’ carnage.

As December 8, 2025, dawns drizzly over Rettendon’s haunted hollows – the Rover long scrapped, the lane a lovers’ lane – the tape tolls like a funeral knell for the freedom fight. “It’s closure – the right men paid,” nods Maleary, whose 2020 book Bent Coppers blew the Marsden whistle. For Whomes and Steele, it’s a cruel coda: free but forever felons. The Essex Boys? Buried in infamy, but their ghosts gun for one last gasp. In the murk of murder mysteries, truth’s the deadliest shot – and this bullet’s just found its mark.

News

Fairy-Tale Fadeout: How Barcelona’s Unsung Heroes Busquets and Alba Rode Messi’s Magic to an MLS Cup Miracle – And Hung Up Their Boots in Glory.

The confetti rained down like a pink-and-black blizzard over Chase Stadium, but for Sergio Busquets and Jordi Alba, it felt…

The Silent Carry: Haunting CCTV Shows Texas A&M Cheerleader Brianna Aguilera Limp in a Stranger’s Arms – Minutes After the Game, Hours Before She Died.

It’s only 11 seconds of grainy black-and-white video, but it has broken an entire state in half. 9:39 p.m., November…

“You Broke Me First”: The Four-Page Goodbye Letter That Turned a Long Island Breakup into a Murder Scene.

It wasn’t a text. It wasn’t a Snapchat. It was four sheets of college-ruled paper, folded into a perfect square…

Born into Greatness: Thiago Messi Never Had to Wonder if His Dad Was the Best… Because He Watched It Happen Live.

Imagine opening your eyes to the world and the first thing you ever see is 80,000 people screaming your father’s…

“I’m Sorry Mom” – The 22-Second Recording That Was Supposed to End the Case… Until Her Mother Heard What Police Cut Out.

Everyone thought the nightmare was finally over. At 10:17 a.m. on December 11, 2025, the Austin Police Department played a…

From Fairy-Tale Kisses to a Fatal Fight: The Heartbreaking Last Photos of Texas A&M Cheerleader Brianna Aguilera and the Boyfriend She Screamed at Minutes Before She Fell.

They looked untouchable. On October 30, 2025, exactly 29 days before Brianna Aguilera’s lifeless body was found 170 feet below…

End of content

No more pages to load