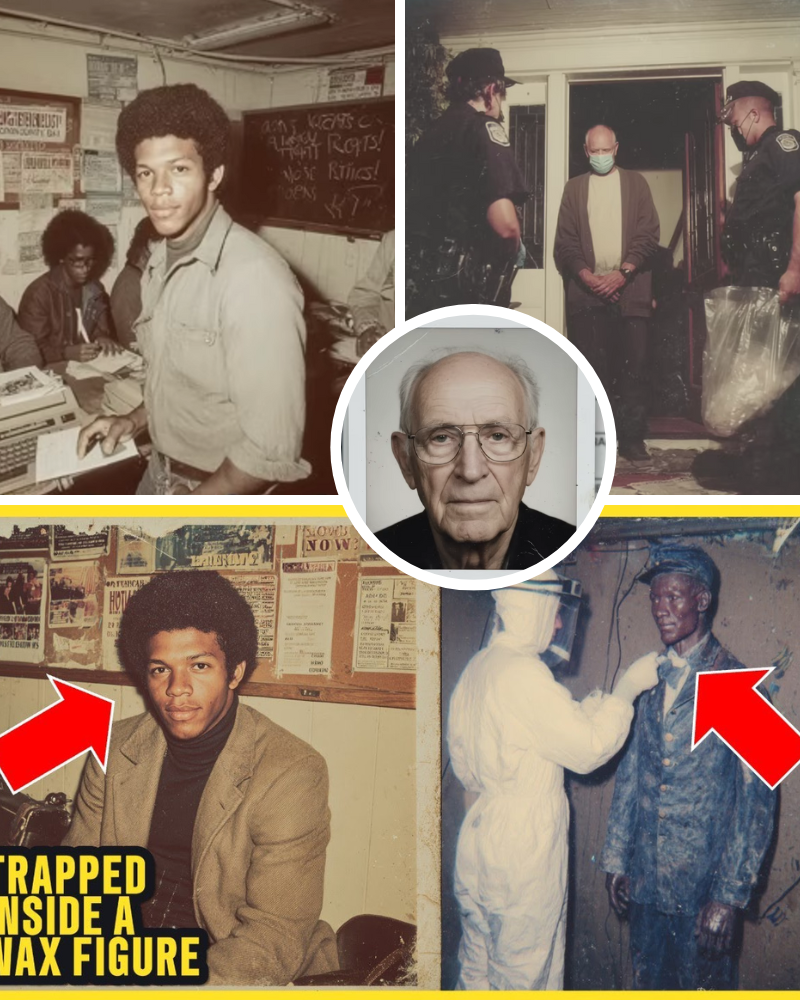

In the quiet halls of the Alistair City Museum, a 19th-century cotton warehouse turned historical landmark in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, a chilling secret lay hidden for half a century. Since 1974, a wax figure of an unnamed Black Union soldier, celebrated for its “haunting realism,” stood as the centerpiece of the museum’s Civil War exhibit, drawing thousands for its lifelike details—a scarred brow, calloused hands, and piercing eyes. But in July 2025, Dr. Maya Vincent, a 36-year-old curator hired to modernize the aging collection, uncovered a horrifying truth: The figure wasn’t wax at all, but the preserved body of Lionel Vance, a Black activist who vanished in 1973 after clashing with local powerbrokers. An after-hours X-ray revealed not only human remains but signs of a violent death—cracked ribs, a fractured skull—turning a beloved exhibit into a 50-year-old crime scene and implicating the museum in a chilling cover-up.

The Exhibit’s Origins: A 1974 Triumph with Dark Roots

The figure debuted on June 14, 1974, amid a wave of bicentennial fervor, as the Alistair City Museum sought to broaden its Confederate-heavy Civil War narrative. Commissioned from Marcel Dubois, a reclusive New Orleans sculptor known for hyper-realistic waxworks, the statue depicted a soldier of the 1st Louisiana Native Guard, a Black Union regiment that fought at Port Hudson in 1863. Standing 5’11” in a tattered blue uniform, musket slung over shoulder, it captivated visitors. “It’s like he’s alive,” a 1974 Baton Rouge Advocate review marveled, praising Dubois’s “uncanny craft.” Museum director Harold Grayson claimed it was modeled on “archival sketches,” with no specific soldier named, per exhibit notes. By 1975, it drew 12,000 visitors yearly, a star attraction alongside muskets and faded diaries.

The figure’s realism sparked whispers. Night guards reported an eerie “presence”; a 1982 docent claimed it “sweated” under heat lamps. Yet, its origins went unquestioned, maintained by Dubois’s studio until his 1998 death. The museum’s 1970s staff, led by Grayson (died 1990), leaned on its prestige, while Dubois’s invoices—vague about materials—raised no red flags. For 50 years, the soldier stood sentinel, its secret buried under wax and time.

Dr. Maya Vincent’s Breakthrough: A Scar That Spoke

Dr. Maya Vincent, a Howard University-trained historian specializing in African American military history, joined the museum in March 2025 to diversify its exhibits. Tasked with cataloging artifacts, she turned to the soldier, intrigued by its lack of provenance—no contract details, no model records. “Museums don’t just lose paperwork for a centerpiece,” she told NPR in September 2025. Her suspicions grew during a June 28 inspection, when she noticed a crescent-shaped scar above the figure’s left eye, too organic for wax. Comparing it to missing persons files, she stumbled on Lionel Vance, a 28-year-old activist reported missing in October 1973 after organizing voter drives in Baton Rouge’s Black communities.

Vance, a Vietnam vet and Southern University grad, was a firebrand who clashed with local elites over desegregation policies. His last sighting—September 29, 1973, at a diner near the museum—aligned with Dubois’s commission timeline. Vincent, risking her job, conducted a covert X-ray on July 12, 2025, using a borrowed LSU medical scanner. The results were staggering: A human skeleton, with a fractured skull and three broken ribs, lay beneath the wax, preserved by a formaldehyde-based compound. “I felt sick,” Vincent said. “This was a man, murdered, displayed like a trophy.” She alerted Baton Rouge PD, who sealed the exhibit on July 15, citing “structural concerns.”

The Cold Case: Lionel Vance’s Lost Story

Baton Rouge PD’s investigation, led by Detective Marcus Reed, zeroed in on Vance. Missing persons records described him as 5’11”, 165 pounds, with a distinctive scar from a 1971 protest injury—matching the figure’s mark. Dental records, pulled from veteran files, showed a 92% match, pending DNA confirmation from a cousin in Shreveport. Evidence pointed to violence: The skull fracture suggested a blunt-force blow, and rib breaks indicated a struggle, per a coroner’s August 2025 report. Chemical analysis revealed a preservation process—formaldehyde and resin—used in 1970s mortuary science, masking decay for decades.

Suspicion fell on Marcel Dubois, whose studio records, recovered from a Kenner warehouse, listed 1973 purchases of “cadaver-grade preservatives” and a cryptic note: “Urgent commission, no questions.” Dubois, who battled debts after a 1972 studio fire, had ties to a New Orleans mortician, Leon Carter, arrested in 1974 for selling unclaimed bodies but never convicted. Detectives theorize Dubois, under pressure to deliver the museum’s statue, acquired Vance’s body—possibly via Carter—after an unsolved murder. A 1973 police report notes Vance’s run-ins with local vigilantes tied to segregationist groups, hinting at a targeted killing. “This wasn’t random,” Reed told The Advocate. “Vance was a threat to someone powerful.”

Museum records offer no clarity. Grayson’s 1974 memos praise Dubois’s “miracle delivery” but dodge specifics. A retired curator, Evelyn Tate, 79, admitted to WAFB in 2025: “We didn’t ask how he did it—just marveled.” The exhibit’s low lighting and restricted access hid imperfections, letting the secret fester.

A City’s Reckoning: Justice and Remembrance

The revelation stunned Alistair City. The museum closed for a week in August 2025, facing protests from Black Lives Matter activists demanding accountability and Vance’s dignified burial. “He was erased, then exploited,” Vincent said at a July vigil, attended by 2,000. X posts under #JusticeForLionel hit 1 million, with TikTok true-crime videos blending museum photos and protest chants gaining 4 million views. Community leaders called for renaming the exhibit hall for Vance, while the museum pledged a $500,000 fund for Black history research, inspired by advocates like Rihanna’s Clara Lionel Foundation.

Critics slam the museum’s negligence, pointing to lax 1970s oversight and a cultural blind spot for Black stories. “This was a man, not a prop,” historian Dr. Lena Carter told Louisiana Weekly. Vincent’s discovery, hailed as “fearless” by Essence, has spurred a 2026 exhibit on Black Union soldiers, using real photos and letters. If confirmed as Vance, his remains will be laid to rest in 2026, with a memorial planned near the museum.

The case remains open. Suspects—Dubois and Carter—are deceased, but police probe Grayson’s surviving associates for complicity. As Baton Rouge grapples with its past, Vincent’s find echoes a truth: History’s heroes deserve honor, not concealment. Lionel Vance, once a voice for justice, now demands it from beyond the wax.

News

Rihanna Responds to a Fan Saying, “They Saying It’s 2016, Rih”: What Her Viral Reply Really Means

When a fan recently commented, “They saying it’s 2016, Rih,” few expected Rihanna to respond. She often ignores random online…

Rihanna’s Unmatched Face Card: How One Look Became a Cultural Phenomenon

Few celebrities command attention the way Rihanna does. Across red carpets, candid street photographs, and unfiltered social media moments, one…

400,000 FRANCS FOR RELEASE: PROSECUTORS SEEK BAIL FOR OWNERS AFTER DEADLY CRANS-MONTANA NEW YEAR FIRE

Prosecutors in Sion have requested a total of 400,000 Swiss francs in bail to grant provisional freedom to Jacques and…

📰 RCMP RELEASES NEW TIMELINE DETAILS IN LILLY AND JACK SULLIVAN CASE AS ALLEGED MESSAGES SPARK FRESH CLAIMS

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has entered another sensitive phase as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police released new…

JUST NOW: Investigators Flag Timeline Issues and Re-Examine Key Details in the Disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has taken an unexpected and unsettling turn, according to the latest update released…

A new wave of controversy erupted online this week after the daughter of an NBA legend reportedly came forward with what she described as troubling information involving Stefon Diggs and his relationship with Cardi B.

According to circulating social-media claims, she suggested that Cardi B should reconsider her involvement with the NFL star, citing alleged…

End of content

No more pages to load