Imagine this: crystalline turquoise waters lapping at your feet as you float down a lazy river on an inflated inner tube, the jagged limestone karsts piercing the sky like ancient sentinels. Laughter echoes from rope swings and zip lines, while bars perched on the riverbanks blast thumping bass and hawk buckets of mystery cocktails for pennies. This is Vang Vieng, the backpacker’s utopia in the heart of Laos – a place where adventure meets hedonism, and the line between thrill and tragedy blurs into oblivion. For 24-year-old Calum Macdonald from Sunbury-on-Thames, Surrey, what started as a dream gap-year escapade turned into a nightmare of irreversible darkness. Blinded by a insidious poison hidden in “free shots” at a rowdy hostel party, Calum survived a mass poisoning that claimed the lives of five of his new-found friends. His story isn’t just a cautionary tale; it’s a siren call to the millions of young travelers chasing the high of Southeast Asia’s party hotspots. In an era where wanderlust collides with reckless abandon, how many more must lose their sight – or their lives – before we heed the warning?

Calum’s ordeal began on a balmy November evening in 2023, a time when Vang Vieng was riding the crest of its post-pandemic resurgence. The town, nestled along the serpentine Nam Song River, had long shed its reputation as a hedonistic hellhole – or had it? Once infamous for “tubing,” a boozy rite of passage involving floating downstream while stopping at bar after bar for mud volleyball, free shots of rice whiskey, and buckets of vodka-Red Bull that could fell an elephant, Vang Vieng had undergone a facelift. The Laotian government cracked down in 2012, shuttering the most egregious party dens and promoting eco-tourism: kayaking through misty caves, hot-air balloon rides at dawn, and hikes to hidden lagoons that shimmer like emeralds under the sun. By 2023, it was rebranded as a “family-friendly adventure hub,” drawing not just gap-year revelers but Instagram influencers and middle-aged couples seeking serenity amid the chaos.

Yet beneath the polished veneer, the underbelly pulsed with danger. Calum, a fresh-faced finance graduate with a mop of tousled brown hair and an infectious grin, arrived in Vang Vieng with a backpack stuffed with dreams and a liver primed for punishment. “It was everything I’d imagined,” he recalls in a voice still laced with wonder, even as he navigates his world through the haze of audio descriptions and guide dogs. “The air smelled like jasmine and adventure. We tubed for hours, leaping off swings into water that felt like liquid silk. By night, the bars lit up like fireflies, and everyone was your instant best mate.”

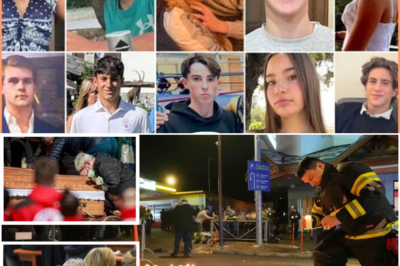

It was on one such tubing excursion that Calum crossed paths with the group that would become his unwitting co-conspirators in catastrophe. Freja Vennervald Sorensen, a 21-year-old Danish art student with sun-kissed freckles and a laugh that cut through the din, and her roommate Anne-Sofie Orkild Coyman, 20, a bubbly linguistics major from Copenhagen, were the epitome of Scandinavian cool. They’d bonded over shared playlists of indie folk and cheap mango smoothies. Then there were the Aussies: Holly Morton-Bowles, 26, a yoga instructor from Sydney whose free-spirited vibe masked a fierce loyalty, and her 19-year-old cousin Bianca Jones, a wide-eyed uni freshman chasing her first taste of independence. Rounding out the tragic ensemble were Simone White, a 28-year-old British corporate lawyer from Manchester, on a solo sabbatical to “find herself” away from boardrooms and burnout, and James Louis Hutson, a 57-year-old American retiree from Texas, whose salt-and-pepper beard and tales of Vietnam War-era exploits made him the group’s unlikely sage.

Their fateful convergence happened at the Blue Lagoon, Vang Vieng’s crown jewel – a series of azure pools fed by freshwater springs, surrounded by swing sets that arc 20 feet into the air. Adrenaline surged as they whooped and splashed, the sun dipping low and painting the cliffs in hues of burnt orange. By dusk, the energy shifted from playful to primal. They piled into tuk-tuks back to town, dust clouds billowing behind them, and ended up at Nana Backpackers Hostel – a ramshackle haven of thatched roofs, hammocks, and a bar that promised “all-you-can-drink” deals for under £5 a night.

What happened next unfolded like a scene from a binge-watch thriller, but with stakes far graver than fiction. The hostel, a labyrinth of bunk beds and fairy lights, was hosting a “Welcome to the Jungle” themed bash. Neon body paint glowed under blacklights, and a DJ spun remixes of backpacker anthems like “Wagon Wheel” and “Riptide.” The drinks flowed freely – or so it seemed. “They were handing out these shots like candy,” Calum says, his tone shifting from nostalgic to haunted. “Lao-Lao rice whiskey, they called it. Strong stuff, but hey, it was free. We clinked glasses, toasted to new friends, and knocked them back. Freja was doing this silly dance, Anne-Sofie was challenging everyone to beer pong. It felt invincible, you know? Like nothing could touch us.”

Unbeknownst to the revelers, those “free drinks” harbored a silent assassin: methanol, a toxic industrial alcohol masquerading as ethanol. Bootleggers in cash-strapped regions like Laos sometimes cut corners, diluting legitimate spirits with methanol to stretch supplies and profits. Tasteless, odorless, and cheaper than dirt, it’s the perfect poison – until it strikes. By morning, the group had scattered: Calum, nursing a mild hangover, hopped on a 24-hour sleeper bus to Hanoi, Vietnam, eager for the neon chaos of its old quarter. The others lingered, some nursing headaches, others shrugging it off as a wild night.

For Calum, the descent into hell was gradual, then apocalyptic. “About halfway through the bus ride, right at the Laos-Vietnam border, it hit,” he recounts, his fingers tracing the edge of a Braille notepad in his London flat. “My whole vision just… engulfed in this blinding white light. Like staring into the sun, but from the inside out. I blinked, rubbed my eyes – nothing. The world was a snowy blur, like static on an old TV. I figured it was the booze, or maybe altitude sickness. ‘Shake it off, mate,’ I told myself.”

Arriving in Hanoi, the symptoms escalated from disorienting to devastating. Checking into a budget guesthouse, Calum stumbled through the lobby, mistaking shadows for doorways. “I kept asking my mates, ‘Come on, lads, why are we sitting in the dark? Let’s switch the light on.’ They looked at me like I’d lost it – the room was floodlit.” Panic set in when he couldn’t read his phone’s screen to check emails or scroll Instagram. Friends guided him to the Hanoi French Hospital, an international facility where expat doctors speak fluent English and accept travel insurance on faith.

The diagnosis was a gut-punch: methanol poisoning. Blood tests revealed sky-high levels of formic acid, the byproduct that ravages the body’s cells. “The optic nerve is like the canary in the coal mine for methanol,” explains Professor Oliver Jones, a forensic chemist at RMIT University in Melbourne, who has consulted on dozens of such cases. “Your liver converts methanol into formaldehyde, then formic acid. That acid jams up cytochrome oxidase, an enzyme crucial for cellular respiration. Without it, cells can’t process oxygen. The eyes suffer first because the optic nerve is oxygen-hungry and vulnerable. It’s like flipping a switch – lights out, potentially forever.”

Calum’s treatment was a blur of IV drips, hemodialysis machines whirring like angry bees, and the sterile tang of antiseptic. Fomepizole, an antidote that blocks methanol’s metabolism, was administered intravenously, but it was too late for full recovery. He spent three grueling weeks in Hanoi, his world reduced to echoes and textures: the rustle of nurses’ starched uniforms, the metallic bite of hospital Jell-O, the distant honk of Hanoi’s motorbike symphony. Airlifted back to the UK on a medical evac flight, he endured another fortnight at a Surrey eye clinic, where ophthalmologists confirmed the verdict: bilateral optic neuropathy. Blindness, irreversible.

But the emotional shrapnel was yet to detonate. Holed up in his childhood bedroom, surrounded by faded posters of Premier League heroes and shelves of dog-eared fantasy novels he could no longer devour, Calum was shielded from the full horror by his family’s fierce love. His parents, Mark and Lisa Macdonald – a quiet accountant and a schoolteacher, respectively – pored over news alerts in hushed tones. “We couldn’t bear to tell him,” Lisa confesses, her voice cracking over a video call. “He was fighting so hard just to eat, to sleep, to accept this new reality. How do you drop a bomb like that on top?”

Six months later, the truth crashed in like a rogue wave. A well-meaning friend, scrolling through travel forums, stumbled on headlines: “Backpacker Horror in Laos: Five Dead from Bootleg Booze.” Freja and Anne-Sofie, the Danish duo whose giggles had lit up that fateful night, had collapsed within hours of each other, their bodies wracked by seizures before slipping into comas. Holly and Bianca, the Aussie cousins who’d dreamed of temple-hopping in Luang Prabang, never made it off the hostel floor; autopsies pinned their deaths on acute metabolic acidosis from formic acid overload. Simone White, the lawyer whose LinkedIn profile still beamed with conference selfies, was found unresponsive in her bunk, her sabbatical cut short by organ failure. And James Hutson, the Texan storyteller who’d regaled them with yarns of dusty trails and dive bars, succumbed in a Vang Vieng clinic, his family stateside blindsided by grief.

“I was gutted,” Calum admits, the word hanging heavy in the air. “We’d shared a room that night – bunks stacked like sardines, swapping life stories till dawn. I certainly had more to drink than they did, I imagine. Shots on shots, plus those buckets. So why me? Why did I pull through when they… didn’t?” The randomness gnaws at him, a philosophical thorn in his reordered life. Was it luck? Genetics? The fomepizole’s narrow window? Experts like Prof. Jones demur: “Survival’s a crapshoot. Body weight, prompt treatment, even hydration levels play in. Calum got lucky – if you can call blindness lucky.”

Vang Vieng’s methanol massacre wasn’t a freak outlier; it was the latest flare-up in a global epidemic of tainted tipples preying on the young and footloose. The UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) lists eight high-risk hotspots where counterfeit booze has turned honeymoons into hospitals: Bali, Indonesia; Goa, India; Phnom Penh, Cambodia; and yes, Laos among them. In 2023 alone, the World Health Organization tallied over 1,200 methanol-related deaths worldwide, with Southeast Asia’s backpacker trail accounting for a disproportionate slice. “It’s the perfect storm,” says Dr. Maria Elena Rossi, a toxicologist with the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. “Tourist areas have lax regulation, desperate vendors, and thrill-seekers who prioritize price over provenance. A bottle of ‘whiskey’ might be 90% methanol – enough to blind a village.”

Flash back to 2019 in Bali: Eight Australians, including honeymooners, were hospitalized after sipping mojitos laced with the toxin at a Seminyak beach club. Two years prior, in Cambodia’s Koh Rong island, a “full moon party” claimed three French tourists. And in 2024, Goa saw a cluster of six Indian students blinded after downing “desi daru” from a roadside shack. The pattern is chilling: symptoms mimic a brutal hangover at first – nausea, dizziness, the spins – lulling victims into complacency. Then, 12 to 48 hours later, the real reaper arrives: blinding headaches, photophobia (light sensitivity that feels like daggers), “snowfield vision” (a whiteout haze), tunnel narrowing, or total blackout. Seizures follow, then coma, kidney shutdown, death.

Calum’s survival instincts kicked in post-trauma, transforming victim into advocate. Now 26, he’s traded backpack for briefcase, crunching numbers at a City of London fintech firm where screen readers and voice-to-text software level the playing field. “Blindness reshapes you,” he says with a wry chuckle. “I can’t see the Thames from my desk, but I hear its murmur, feel the Tube’s rumble. It’s not the end – it’s a pivot.” In a bold move, he lobbied his MP for awareness campaigns, testifying before a parliamentary select committee on travel safety in spring 2025. “Those last sighted days in Vang Vieng? They haunt me,” he told stone-faced MPs. “But silence helps no one. If my story saves one shot, one life…”

His pièce de résistance: a short film, “Eyes Wide Shut Abroad,” slated for UK secondary schools next term. Co-produced with the FCDO and charities like Sight Savers, it weaves Calum’s animated reenactments with survivor testimonials and animated breakdowns of methanol’s molecular mayhem. “Think of it as ‘Euphoria’ meets ‘Health Class,’” jokes director Zara Khan, whose team filmed Calum voicing his avatar in a makeshift studio. Early screenings at youth hostels have elicited gasps and pledges: “I’ll stick to beer from now on.”

Yet Calum’s message is pragmatic, not puritanical. “Look, it’s unrealistic to expect backpackers not to drink. That’s like banning beaches in Brazil. But smarts matter. Scope the scene: licensed bars over pop-ups, sealed bottles over sketchy buckets. If it tastes off – bitter, like nail polish remover – bail.” He pauses, his unseeing gaze fixed on some inner horizon. “And trust your gut. That white light? It was my wake-up call. Yours might be different.”

The ripple effects extend beyond Calum’s circle. In Vang Vieng, Nana Backpackers shuttered amid investigations, its owner facing manslaughter charges in a Laotian court that’s as labyrinthine as the town’s caves. Tourism dipped 15% in Q1 2024, per Laos National Tourism Authority stats, but locals whisper of a silver lining: a pivot to sustainable stays, with eco-lodges sprouting like bamboo. “We’ve learned,” says Somchai, a former bartender turned cave guide. “No more shortcuts. Visitors come for the soul now, not the shots.”

Globally, the methanol scourge demands reckoning. Interpol’s 2025 Operation Snake Eater busted 47 illicit distilleries across Asia, seizing 20,000 liters of poison. But enforcement lags behind ingenuity; underground labs churn out fakes faster than regulators can raid. “It’s economics,” sighs Prof. Jones. “Ethanol costs a king’s ransom in poor regions. Methanol? Pennies. Until tourists demand – and pay for – quality, it’ll persist.”

For the families left in methanol’s wake, solace is scant. Freja’s mother, Ingrid Sorensen, a Copenhagen florist, clutches a locket with her daughter’s tubing photo. “She was light itself,” Ingrid says softly. “Now, we fight in her name – petitions for EU booze-testing kits at airports.” Bianca’s dad, Mick Jones from Perth, channels fury into a foundation funding antidotes for remote clinics. “Bianca would’ve hated pity,” he grunts. “She’d want action. Test the damn drinks!”

As Calum steps into Parliament’s echoing halls this autumn, cane tapping a defiant rhythm, he embodies resilience’s quiet roar. Blindness stole his sight, but not his spark. “Travel changed me – for the better, scars and all,” he muses. “Vang Vieng’s beauty lingers in memory: those cliffs like dragon’s teeth, the river’s whisper. But paradise has teeth. Bite wisely.”

In a world where wanderlust whispers “go,” Calum’s clarion call echoes: See the world, yes – but see the risks first. The next shot might be your last light. Will you heed it?

News

🚨 Not Just a Bystander: Shocking New Revelations Expose Tess Crosley’s Hidden Proximity to the Neales 😳🕵️♀️

The latest twist in the Jules and Lachie Neale saga has just dropped, and it reveals a startling reality. Tess…

😭 White Coffins, Silent Streets: Across Europe, Families Lay to Rest the Children Lost in the Swiss Nightclub Inferno 🕊️🕯️

The snow-covered peaks of Crans-Montana, usually a glittering playground for the wealthy and adventurous, have been shrouded in grief since…

🚨 Hollywood Shockwave: Timothy Busfield Missing as U.S. Marshals Join Search Over @buse Warrant — Actor Claims Allegations Are ‘Revenge’ 🎭🔥

Timothy Busfield, the Emmy-winning actor best known for his roles in Thirtysomething, Field of Dreams, and The West Wing, has…

📉📢 “Replaced Without a Goodbye? The Real Story Behind Jo Silvagni’s Vanishing Role, the Failed Contract Talks, and the New Faces Taking Over Chemist Warehouse

For more than a decade, Jo Silvagni has been one of the most recognisable faces in Australian retail. With her…

👀🔥 A Hand on His Lower Back at the Wedding 👰♂️💔 Critics Say Tess Crosley ‘Claimed’ Lachie Neale Years Before the Affair Scandal

They say a picture paints a thousand words, but this one screams “betrayal” so loudly that it feels almost unfair…

While Jules Neale Is Rebuilding Her Life, Tess Crosley’s Social Media Moves Are Raising Eyebrows Across Australia

In the cutthroat world of celebrity scandals and sports drama, where reputations are made and shattered in the span of…

End of content

No more pages to load