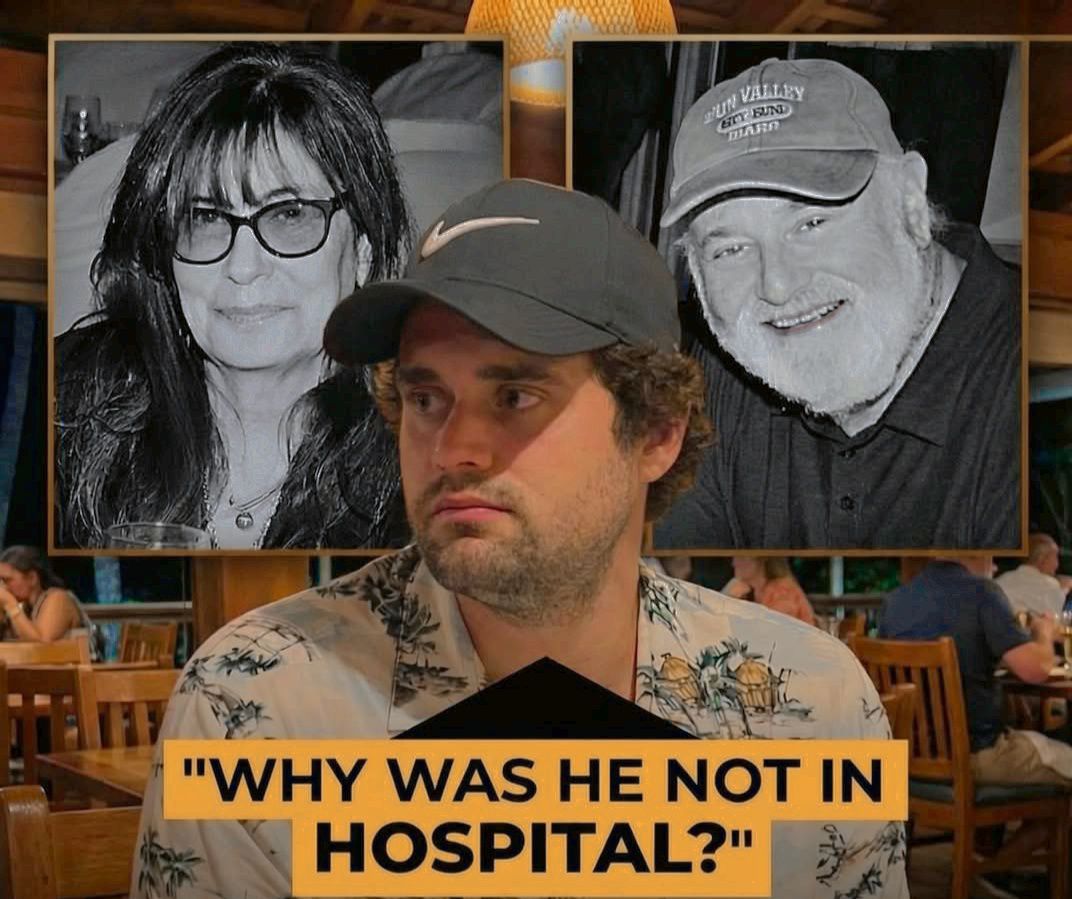

The devastating murders of Hollywood icon Rob Reiner and his wife Michele Singer Reiner by their son Nick have raised profound questions about mental health treatment, particularly for individuals with severe conditions like schizophrenia combined with substance abuse. Reports confirm Nick was diagnosed with schizophrenia years ago, was under psychiatric care, and had his medication adjusted 3-4 weeks before the December 14, 2025, killings—a change that sources say made him increasingly “erratic and dangerous.” He had recently left a high-end Los Angeles rehab facility specializing in dual diagnosis (mental illness and addiction), and his parents were closely monitoring him, even bringing him to a holiday party the night before due to concerns.

Your question—whether involuntary hospitalization under California’s Lanterman-Petris-Short (LPS) Act could have prevented this—is heartbreaking and complex. No one can say with certainty what might have changed the outcome, but let’s examine the facts, the law, and broader insights into preventing violence in such cases.

California’s Involuntary Hold Process (5150 and Beyond)

California’s LPS Act prioritizes civil liberties while allowing temporary involuntary holds when someone poses an imminent risk. Key elements include:

5150 Hold (72 Hours) — Authorized professionals (police, crisis teams, or certain mental health workers) can detain someone if, due to a mental disorder, they are a danger to themselves (DTS), a danger to others (DTO), or gravely disabled (unable to provide food, clothing, or shelter). This requires probable cause of imminent harm—not just a history of illness or erratic behavior.

Extensions — If criteria are still met after evaluation, a 5250 (14-day hold) or longer certifications can follow, often requiring a hearing.

Threshold Challenges — The bar is high: Verbal threats or paranoia alone may not suffice without clear evidence of imminent action. Substance abuse complicates this, as intoxication can mimic or exacerbate symptoms but doesn’t always trigger a hold on its own.

In Nick’s case, reports describe worsening behavior after the medication change—antisocial actions at the party, a loud argument with his father—but no public evidence of explicit threats or acts meeting the “imminent danger” threshold before the tragedy. His parents’ efforts to “keep an eye on him” suggest deep concern, but without a clear trigger (e.g., a direct threat), initiating a 5150 might have been difficult. Even if one had been placed, the short duration (72 hours) and potential release if stabilized highlight the system’s limitations for chronic cases.

Broader Prevention: What Works and What Doesn’t

Schizophrenia itself does not make someone inherently violent—most people with the illness are not. Violence risk rises significantly with untreated symptoms, comorbid substance abuse (as in Nick’s long history), medication non-adherence, or recent changes (which can temporarily worsen psychosis).

Evidence-based approaches to reduce risk include:

Medication Adherence → Antipsychotics like clozapine are highly effective for treatment-resistant cases and reducing impulsive aggression. Long-acting injectables (LAIs) outperform oral meds by addressing non-compliance.

Integrated Treatment → Dual-diagnosis programs tackling both schizophrenia and addiction simultaneously.

Outpatient Commitment → Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT) in some states mandates community treatment; studies show it reduces hospitalizations and violence when paired with intensive services.

Early Intervention → Family support, monitoring, and crisis planning.

Involuntary holds are a last-resort safety net, not a long-term solution. They can stabilize acutely but often fail to address root issues, and overuse risks trauma or distrust. Experts emphasize that most violence linked to mental illness is preventable with consistent, voluntary-leaning care—yet gaps in community resources persist.

Should Nick Have Been Hospitalized Involuntarily?

Hindsight is painful. If clear signs of imminent danger were present (e.g., threats), a 5150 could have provided temporary protection and evaluation. But without that, forcing hospitalization against someone’s will—especially an adult resisting treatment—raises ethical and legal hurdles. Nick’s history shows he preferred home-based or outpatient care, and his family tried everything short of involuntary measures.

Blaming the family or system oversimplifies a tragedy rooted in illness. This case underscores the need for better early intervention, dual-diagnosis resources, and perhaps reformed laws for higher-risk individuals. Ultimately, while involuntary hospitalization might have bought time, true prevention requires robust, accessible mental health support long before crisis.

If you or someone you know is struggling, resources like NAMI (nami.org) or the 988 crisis lifeline can help. Tragedies like this are rare but remind us of the human cost when systems fall short.

News

Nicki Minaj and Rihanna Spark Buzz After Being Spotted Shopping Together

It didn’t take a stage, a red carpet, or a press release to set the internet on fire. When Nicki…

Purple Hearts 2 Confirmed for 2026: Cassie and Luke’s Love Story Isn’t Over Yet

The announcement fans have been waiting for is finally here. Director Elizabeth Allen Rosenbaum and star Sofia Carson have officially…

Old Money Turns Lethal in Season 2 — A Hidden Inheritance Clause Threatens to Destroy the Empire

The Season 2 trailer has arrived, and one thing is immediately clear: this is no longer a story about privilege…

Maxton Hall Season 3 Trailer: A Buried Will, a Stolen Future, and the Collapse of Power

The official trailer for Maxton Hall Season 3 has arrived — and it signals the darkest, most explosive chapter in…

Your Fault: London Season 2 Trailer — The Truth on His Phone Turns Love Into a Game

The official trailer for Your Fault: London Season 2 has arrived, and it signals a sharp, unsettling shift in the…

My Life With the Walter Boys Season 3 Trailer: When the Past Comes Back, Everything Changes

The official trailer for My Life With the Walter Boys Season 3 has arrived, and it signals a dramatic shift…

End of content

No more pages to load