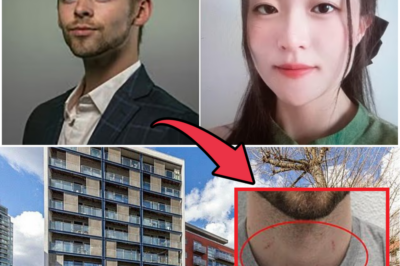

In the unforgiving embrace of Austria’s Grossglockner, where jagged peaks pierce the heavens and winds howl like vengeful spirits, a love story turned into a frozen nightmare that has gripped the world with horror and outrage. On a bitter January night in 2025, 33-year-old Kerstin Gurtner, a vibrant skier from Salzburg whose passion for the outdoors knew no bounds, was allegedly abandoned by her boyfriend just 50 meters shy of the summit. Left unprotected in sub-zero temperatures, hypothermic and disoriented, she succumbed to the merciless cold, her final moments a solitary agony amid the ice. Prosecutors in Innsbruck have charged her partner, 36-year-old Thomas Plamberger, with grossly negligent manslaughter, accusing him of a cascade of fatal errors that transformed a romantic alpine adventure into a preventable tragedy. As webcam footage emerges showing two flickering headlamps ascending—and only one descending—the question echoes across the Alps: How could a seasoned climber leave the woman he loved to die alone on the mountain? With a trial looming in February 2026, the case exposes the razor-thin line between thrill-seeking and criminal neglect, leaving families shattered, communities reeling, and adventurers everywhere questioning their own pursuits.

Kerstin Gurtner was no stranger to the call of the wild. Born and raised in the picturesque city of Salzburg, nestled in the shadow of the Austrian Alps, she grew up with skis strapped to her feet and a backpack always at the ready. Friends and family describe her as a “force of nature”—a 5-foot-6 bundle of energy with flowing auburn hair, piercing green eyes, and an infectious laugh that could warm even the coldest winter day. By day, she worked as a marketing consultant for a local tourism firm, promoting the very mountains that would claim her life. But her true passion lay in the outdoors: weekend hikes in the Salzkammergut region, cross-country skiing marathons, and summer treks through the Hohe Tauern National Park. “Kerstin lived for the adrenaline,” her sister, Martina Gurtner, shared in a tearful interview with local media. “She wasn’t reckless—she was alive. Every photo of her shows that spark.” Social media tributes paint a vivid portrait: Instagram posts of her conquering the Dachstein glacier, beaming atop snow-capped ridges, or sharing fondue with friends after a day on the slopes. Yet, for all her experience on skis, Kerstin was not a hardened alpinist. She preferred groomed trails to technical ascents, and her gear reflected that—sturdy but not summit-ready for the beast that is Grossglockner.

Grossglockner itself is a colossus, Austria’s highest peak at 3,798 meters (12,461 feet), a magnet for thrill-seekers and a graveyard for the unprepared. Named after the “big bell” shape of its summit, it’s part of the Glockner Group in the Eastern Alps, drawing over 5,000 climbers annually. But winter ascents are a different beast: avalanches lurk in every crevasse, temperatures plummet to -20°C (-4°F), and winds whip at 100 km/h (62 mph). The standard route, via the Stüdlgrat ridge, demands ice axes, crampons, and unyielding stamina—skills honed through years of training. Historical tragedies abound: in 2018, a British climber fell to his death; in 2022, a group of four perished in a blizzard. “It’s not a hike; it’s a war with nature,” says veteran guide Hans Mueller, who has summited 50 times. “One mistake, and you’re history.” For Kerstin and Thomas, that war began on January 18, 2025, under a sky heavy with foreboding clouds.

The couple had met two years earlier at a Salzburg ski lodge, bonding over shared tales of powder runs and sunset vistas. Thomas Plamberger, a software engineer by trade, was the more seasoned adventurer—a certified mountaineer with conquests including Mont Blanc and the Matterhorn. Friends say he planned the Grossglockner trip as a “romantic challenge,” a way to push their limits together. But red flags waved from the start. They departed late, around noon, from the Lucknerhaus hut at 1,920 meters, ignoring warnings of deteriorating weather. Snowfall had blanketed the trails, and forecasts predicted gale-force winds. Kerstin’s equipment was inadequate: lightweight boots ill-suited for ice, no harness for roped sections, and minimal insulation against the freeze. Thomas, as the “guide,” carried the bulk of the gear—emergency blankets, a bivouac sack, and a satellite phone—but prosecutors argue he failed to deploy them effectively.

As dusk fell, the ascent grew grueling. They roped up for the exposed ridges, but Kerstin’s pace slowed. By midnight, near the 3,748-meter summit cross, exhaustion hit like an avalanche. Hypothermia set in—her body temperature dropping, confusion clouding her mind, fingers numb from frost. Witnesses? None, save the silent stars and a distant webcam at the Adlersruhe hut, capturing ghostly pinpricks of light: two headlamps inching upward in tandem. Then, tragedy unfolded. Around 2 a.m., Thomas allegedly made the fateful decision: untie the rope, leave Kerstin huddled 50 meters below the summit, and descend solo. “She was too weak to continue,” he later told rescuers, claiming he aimed to fetch help from the valley. But why not bivouac together? Why not use the emergency gear to shield her? And why silence his phone, missing urgent callbacks from mountain rescue?

The webcam footage, now a haunting centerpiece of the prosecution’s case, tells a tale of abandonment. Two lights ascend; one flickers out, stationary, as the other retreats. Kerstin’s lamp, believed to be the fading one, extinguishes around 3 a.m.—a poignant symbol of her life ebbing away in isolation. Thomas reached safety by dawn, but his call to rescue came too late, at 3:30 a.m., after ignoring earlier alerts. A helicopter buzzed overhead at one point, its spotlight sweeping the slopes—he didn’t signal it. “Multiple opportunities squandered,” Innsbruck prosecutors stated in their indictment. “As the experienced leader, he bore responsibility for her safety.” By the time teams located Kerstin the next day, her body was encased in ice, mere feet from salvation. Autopsy confirmed hypothermia as the cause, her core temperature below 28°C (82°F), organs shut down in a final, frozen surrender.

The fallout was swift and searing. On December 5, 2025, authorities publicly identified Kerstin, unleashing a torrent of grief and fury. Social media erupted with #JusticeForKerstin, memes juxtaposing romantic summit selfies with grim crime scene sketches. “How do you leave your love to die?” one viral post queried, amassing 2 million views. Martina Gurtner, speaking for the family, decried Thomas as “a coward who prioritized self over soul.” Vigils in Salzburg drew hundreds, candles flickering against alpine winds, while mountaineering forums dissected the ethics: “In the mountains, you never leave a partner,” wrote one veteran on Alpinforum.de. Thomas, released on bail, has maintained innocence through his lawyer, claiming “panic clouded judgment” and that Kerstin urged him to go. But evidence mounts: phone logs show silent mode during descent; gear unused in his pack; and a prior argument overheard at the hut about her “holding him back.”

Experts weigh in with damning precision. Dr. Elena Fischer, a hypothermia specialist at Vienna Medical University, explains the physiology: “Hypothermia hijacks the brain—confusion, lethargy, then coma. With proper shelter, survival odds soar to 80%. Abandonment? It’s a death sentence.” Mountaineering instructor Karl Becker, who trains on Grossglockner, faults the planning: “Late start in winter? Suicide pact. No rope discipline, no signals—textbook negligence.” Comparisons to infamous cases abound: the 1996 Everest disaster, where guides like Rob Hall stayed with clients to the end; or 2019’s Nanga Parbat, where a climber’s abandonment sparked global debate. “This isn’t bad luck; it’s betrayal,” Becker asserts. Legal minds predict a tough trial: Austrian law on grossly negligent manslaughter requires proving “reckless disregard for life,” with up to three years’ imprisonment. Prosecutors aim to portray Thomas as a hubristic “guide” who valued summit glory over human bonds.

The broader implications ripple through Austria’s outdoor community. Tourism officials in Tyrol report a 15% dip in winter bookings, climbers second-guessing partners. “Trust is everything up there,” says a Grossglockner hut keeper. Safety campaigns surge: mandatory GPS beacons, partner contracts, hypothermia drills. Kerstin’s legacy? A foundation in her name, funding alpine education for women. As February 2026 approaches, the courtroom in Innsbruck will become a theater of reckoning—will justice thaw the ice of her loss, or leave more questions buried in snow? In the Alps’ eternal silence, Kerstin’s story whispers a warning: Love may conquer all, but the mountain forgives none.

News

😱 BREAKING UPDATE IN VIRGINIA COACH SCANDAL: Fugitive Football Hero Travis Turner’s Handgun FOUND Deep in Appalachian Wilderness — But WHERE Is He??

In a jaw-dropping twist that has sent shockwaves through this tight-knit coal-country community and across America, Virginia State Police announced…

😨 APPALACHIAN MYSTERY DEEPENS: Fugitive Coach’s Handgun Located in Rugged Woods, But No Sign of Turner — Veteran Detectives Warn of a “Disturbing Outcome” 🔍🔥

In a jaw-dropping twist that has sent shockwaves through this tight-knit coal-country community and across America, Virginia State Police announced…

🌲🔥 DARK DISCOVERY LOOMS: Veteran Officer Fears Turner Was Consumed by Wildlife — Feds Mobilize Extra Units in Urgent Child-Safety Case 👮♂️⚠️

In the shadow of the ancient Appalachian Mountains, where Friday night lights once illuminated dreams of gridiron glory, a nightmare…

Authorities Fear Travis Turner Was Mauled in the Forest as Federal Teams Boost Search Connected to ‘Grave Ch!ld-Related Allegations’ 😱

In the shadow of the ancient Appalachian Mountains, where Friday night lights once illuminated dreams of gridiron glory, a nightmare…

🌲🔥 FOREST HORROR THEORY EMERGES: Missing Football Hero May Have Been Savaged by Wildlife — Feds Double Their Efforts in High-Stakes Investigation 👮♂️⚠️

In the shadow of the ancient Appalachian Mountains, where Friday night lights once illuminated dreams of gridiron glory, a nightmare…

😳 TRUE-CRIME BOMBSHELL: Spoiled Chicago Teen Found Guilty in Vicious London Attack After Private Health Dispute — Left Girlfriend Injured While He Sought Legal Advice 🔥⚖️

The mask finally slipped off the all-American golden boy Monday when a British jury delivered a thunderous guilty verdict that…

End of content

No more pages to load