In the quiet suburbs of Northampton, where manicured lawns stretch like green carpets under overcast English skies, Lucy Connolly stares out her kitchen window, a cup of cooling tea forgotten in her hand. The world outside hums with the mundane—children on bikes, a neighbor clipping hedges—but inside this unassuming three-bedroom semi-detached home, the air is thick with the residue of a storm that tore through her life like a Category 5 hurricane. It’s been just over three months since Lucy, a 42-year-old childminder with a laugh that once lit up rooms, walked free from the cold grip of HMP Peterborough after serving 377 excruciating days of a 31-month sentence. Her crime? A single, incendiary tweet fired off in the blistering heat of grief and fury following the unthinkable tragedy in Southport.

Picture this: July 29, 2024. Three little girls—Bebe King, six; Elsie Dot Stancombe, seven; and Alice Dasilva Aguiar, nine—lie lifeless on the blood-soaked floor of a Taylor Swift-themed dance class. Their dreams of sequins and Swiftie anthems shattered by a 17-year-old’s blade in a frenzy that would ignite a national inferno. As news helicopters buzzed overhead and social media erupted in a cacophony of horror and speculation, Lucy—mother to a 13-year-old daughter, Edie, and caregiver to other families’ precious little ones—felt the ground shift beneath her. Like millions across Britain, she devoured the reports, her heart pounding with a mother’s primal terror. Rumors swirled: the attacker was an asylum seeker, an illegal immigrant, a monster slipped through the cracks of a porous border. In that red-hot moment of rage, Lucy typed words she would later regret but never fully renounce.

“Mass deportation now. Set fire to all the fing hotels full of the b***s for all that I care. While you’re at it take the treacherous government and politicians with them. I feel physically sick knowing what these families will now have to endure. If that makes me racist, then so be it.”

The tweet, born of visceral anguish, vanished from her X account (formerly Twitter) within hours. A walk with the family dog, a deep breath, a flicker of sanity—she deleted it, convinced the digital ether had swallowed her outburst whole. But screenshots have a way of resurrecting the dead, and eight days later, as riots scorched the streets from Southport to London, her words resurfaced like a vengeful ghost. Viral. Vilified. The spark that would consume her world.

Today, as winter’s chill seeps through the cracks of her home, Lucy Connolly isn’t just a woman rebuilding her life; she’s a lightning rod in Britain’s festering debate over free speech, immigration, and the iron fist of a government desperate to douse the flames of unrest. “Everyone’s living in fear,” she tells me, her voice a mix of steel and sorrow, eyes flashing with the fire that prison couldn’t extinguish. “This isn’t the Britain we want—the one where a slip of the tongue lands you in a cell while the real monsters walk free. We’re all tiptoeing around our own thoughts, afraid the thought police will come knocking. Is this what we’ve become? A nation of silenced souls?”

Lucy’s story isn’t just hers; it’s a mirror held up to a fractured society. It’s the tale of a woman who lost a year of her life, a daughter who wept through weekends of shattered dreams, and a family clinging to normalcy amid a media maelstrom and political vendetta. But to understand the depth of this abyss, we must rewind to that fateful summer, when hope danced in the hearts of children and despair clawed at the edges of a nation’s soul.

The Southport stabbings didn’t just claim three young lives; they cleaved open wounds long festering in Britain’s body politic. For years, the small coastal town of Southport had been a postcard of seaside charm—pier-side ice creams, sandy beaches kissed by the Irish Sea, families strolling the promenade under lazy July suns. But beneath the idyll lurked tensions: an influx of asylum seekers housed in local hotels, whispers of strained resources, and a growing chorus of frustration from residents who felt their voices drowned out by Westminster’s distant decrees. When the attack unfolded, the shockwaves rippled far beyond Merseyside. Parents like Lucy, whose days revolved around playground chats and packed lunches, were thrust into a nightmare of “what ifs.” What if that blade had found Edie at her gymnastics class? What if the unchecked borders her government promised to secure had failed her child?

Lucy’s anxiety wasn’t abstract; it was forged in fire. In 2011, her world had crumbled when her 19-month-old son, Ethan, slipped away due to catastrophic hospital negligence—a birth injury mishandled, a tiny life snuffed out before it could bloom. The grief lingers like a shadow, manifesting in hyper-vigilance, a mother’s radar perpetually scanning for threats. “Every time I drop Edie off somewhere, my stomach twists,” she confesses, her fingers tracing the rim of her mug. “Gymnastics that day? I was pacing the house, imagining the worst. Those poor girls in Southport—they were just like her, full of spark and sparkle. When the rumors hit about the attacker being an illegal, it wasn’t hate talking. It was fear. Raw, gut-wrenching fear for my girl.”

That fear birthed the tweet, a digital Molotov cocktail lobbed into the bonfire of public outrage. But what followed wasn’t just personal ruin; it was a meticulously orchestrated takedown, laced with the acrid scent of political expediency. Lucy’s husband, Ray, isn’t just any spouse—he’s a Conservative local councillor, a pillar of the Northampton community with a reputation for fair play and quiet competence. Their union, a blend of her nurturing warmth and his steady resolve, made them a target-rich environment for those hunting scalps in the riot’s aftermath.

The witch hunt ignited on August 6, 2024. As plumes of smoke still curled from torched hotels and police lines held firm against surging crowds, officers pounded on the Connollys’ door. Lucy, mid-conversation with a client about bedtime routines, was hauled away in handcuffs. “It was surreal,” she recalls, her voice dropping to a whisper. “Ray’s face—pale as death—Edie frozen on the stairs, clutching her phone like a lifeline. They wouldn’t even let me hug her goodbye.” Questioned for hours at the station, she was released on bail with a gag order: no social media, no stirring the pot. Relief was fleeting. Three days later, as Prime Minister Keir Starmer thundered from the dispatch box about crushing “thugs” online and offline, the net tightened. A second arrest, this time with charges: inciting racial hatred under the Public Order Act 1986.

Enter the BBC, that behemoth of public broadcasting, whose role in this drama raises eyebrows sharper than a tabloid headline. Despite clear guidelines urging restraint in naming uncharged suspects—especially to avoid prejudicing trials—the Corporation splashed Lucy’s name across its digital front page. “Tory councillor’s wife charged over Southport tweet,” screamed the subhead, indelibly linking her fate to her husband’s politics. “It was a feeding frenzy,” Lucy says, bitterness etching lines around her mouth. “They didn’t just report; they branded. Every article since? ‘Tory councillor’s wife.’ As if that’s my identity, my sin. Ray jokes we’ll get a license plate—TCW—but it’s no laughing matter. It turned a family crisis into a political assassination.”

Was it coincidence or calculus? Lucy believes the latter, pointing to Starmer’s frantic pivot from the riots’ root causes—the attacker’s known history with police and counter-terror units, details buried under layers of misinformation—to a narrative of “far-right agitators” and their enablers. “He needed a villain,” she asserts, leaning forward, eyes locked on mine. “And who better than the wife of a Tory? It deflected from the failures: the unchecked migrant hotels, the Prevent program’s blind spots. I was the sacrificial lamb, low-hanging fruit for a PM sweating under the spotlight.”

The trial unfolded like a Greek tragedy, swift and merciless. Advised by lawyers to plead guilty—fearing a media-saturated not-guilty plea would drag her deeper into purgatory—Lucy stood in Northampton Crown Court on October 17, 2024, her voice trembling as she owned her words. “I was shaking, a wreck,” she admits. “The judge’s face—stone cold. Thirty-one months. I thought I’d misheard. Seven years was on the table; this was ‘mercy.’” But mercy it was not. Behind bars, the real sentence began: isolation from Edie, the slow erosion of family bonds, the relentless grind of prison life.

HMP Peterborough, a sprawling fortress of regret on the city’s outskirts, swallowed Lucy whole. Category C for women, it echoed with the sobs of the broken and the bravado of the hardened. “First night? Petrifying,” she shudders. “They said seven years—Edie turning 19, the dog long gone. I sobbed into my pillow, bargaining with God I didn’t believe in.” Routine became her anchor: wake at 6 a.m., slop for breakfast, endless hours in a cell no bigger than a closet. But the true torment was the separation. Edie, thrust into adolescence without her mother’s steady hand, unraveled. “She was my shadow,” Lucy says, tears welling. “Now? Anger her armor. Suspended from school for the first time—arguing with teachers, lashing out. Her reports came via Ray: ‘Edie’s struggling, withdrawn.’ I’d lie awake, helpless, fists clenched under the thin blanket.”

Ray, battling aplastic anaemia—a bone marrow betrayal that saps his strength and demands immunotherapy’s toxic embrace—held the fort with grim determination. “I was a ghost,” he tells me later, his engineer’s precision cracking under the weight. “Bills piling, Edie slamming doors, work a blur. Family rallied—my sister cooking, Mum minding Edie—but nights? I’d stare at the ceiling, wondering if Lucy would break first or me.” Christmas 2024 was a dagger twist: Ray and Edie visiting on Eve, her small face pressed to the glass. “Mummy, come home,” she’d beg. “How do you show presents through a screen?” Lucy’s voice cracks recounting it. “I faked cheer on the phone Christmas Day, hearing wrappers tear. Cute? Agonizing.”

The cruelties compounded. Requests for temporary release—day passes to stitch wounds—were stonewalled. Edie’s teachers penned pleas: “The child needs her mother; her grades plummet, her spark dims.” Ray invoked his illness. Denied. Whispers reached them: a Zoom with then-Home Secretary Yvette Cooper, the governor citing “media interest” as poison. “Independent my foot,” Lucy scoffs. “It reeked of orders from on high. Starmer’s two-tier justice: leniency for some, the boot for voices like mine.”

Even the justice system, in a rare mea culpa, admitted flaws. A November 2025 letter from Northamptonshire Police’s Professional Standards Department dismantled Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) fabrications that tainted her case. The CPS had claimed Lucy confessed disdain for “immigrants in general,” not just illegals—a slur implying blanket racism. The police recordings proved otherwise: her ire targeted criminal border-crossers, not migrants writ large. “A vital distinction,” the letter noted, “as the former smacks of prejudice, the latter of lawful concern.” Further, no trove of “racist tweets” existed beyond the one in question and a single, ill-advised “pikey” banter with a friend—pejorative slang for Travellers, but contextually harmless horseplay about caravans.

“The CPS threw me to the wolves,” Lucy fumes. “Lies in press releases, BBC amplifying the echo. I’m suing—mark my words.” Her one other flagged post? That “pikey” quip, a relic of casual insensitivity she owns but contextualizes. “Banter, not bile. But they spun it into a pattern. No other racism on my feed—clean as a whistle.”

Release came August 21, 2025, a sun-dappled dawn that felt like rebirth. Protesters—mums from migrant hotel vigils, dads clutching placards—cheered her exit, hailing her as martyr to Starmer’s “authoritarian Britain,” as Reform UK’s Nigel Farage dubbed it. Support flooded in: letters from Bangladeshi families she’d minded, Lithuanian parents grateful for her warmth, even Afghan refugees she’d cradled through teething nights. “You’re no racist,” one read. “You’re us—a mum protecting her own.” Councillors of color crossed aisles to back Ray; Labour whites bayed for his head.

Yet freedom’s bloom wilted fast. Probation till March 2027 chains her: terrorist-level restrictions, no unapproved travel, constant digital surveillance. Leftist vigilantes troll her mentions, filing bogus reports— “She’s inciting again!”—each triggering probation probes. “I live in fear of a knock,” she admits. “One wrong word, back to the cage.” But fear forges resolve. “I’ve hardened. The BBC’s ‘racist’ label? It stung once. Now? Badge of dishonor on them.”

Lucy’s unbowed, her views unapologetic. “I’m no bigot. That tweet? Heat-of-moment horror, not hatred. I spoke of illegal influxes—hotels bulging with unchecked men while our kids play in shadows. It’s not race or faith; it’s safety. Thousands roaming, vetted by whom? I won’t recant. Britain bleeds from open veins—deportations delayed, resources ravaged. Those Southport angels? Their blood cries for action.”

Her fire ignites broader blazes: free speech’s fragility in a surveillance state. “We fought wars for this—trenches, beaches, ballots. Now? A tweet jails you, while riot-inciters walk or get slaps on wrists.” She cites disparities: far-Left agitators unchained, BLM marchers forgiven firebombs. “Two-tier? It’s a chasm. Starmer’s Stasi—thought crimes punished, real crimes coddled.”

But amid the crusade, heartbreak pulses. Edie, that vibrant 13-year-old with her mother’s eyes and a dancer’s grace, bears scars unseen. Post-release, joy’s reunion soured swift. Just weeks ago, the secondary school Edie pinned hopes on—a fresh canvas post-mum’s absence—yanked her spot. “Thursday call from her current head: ‘New school’s out. Racism won’t fly; parents might riot knowing your mum.’” Edie barricaded in her room, sobs echoing down halls. “She needed reset,” Lucy chokes. “We toured it—smiles, promises. Excitement sparked, first in ages. Now? Crushed.”

Lucy’s complaint flew: “Woke politics poisoning playgrounds? Punish the child for the parent’s past?” Echoes of discrimination chill her. “A vulnerable girl, mum-forsaken for a year, iced out. Insane. I’ll fight—Ofsted, lawyers, the lot.” Edie’s armor thickens: sass to teachers, walls against whispers. “No mum for 377 days? That’s a void words can’t fill. If it were me at 13? Shattered.” Therapy beckons, but Lucy treads soft. “Rebuild slow. She’s my world—giggles over tea, braids before bed. Prison stole that; I won’t let bias steal more.”

Ray nods, his frame frailer but spirit unbent. “We’re stitching quilts from tatters. Councillor’s perks? Frozen—colleagues distant, whispers venomous. But support surprises: ethnic Labour voices in solidarity. Humanity endures.”

As dusk drapes Northampton, Lucy rises, resolute. “Anger over my words outstrips fury for those dead girls? Perverse. I won’t cower. Free speech? Our oxygen. Bully us silent, and what’s left? Echo chambers of approved thought.” She eyes the horizon, where streetlamps flicker to life. “Britain, wake up. Fear’s the real jailer. Fight for words, for kids like Edie, for sanity.”

Lucy’s odyssey—a tweet’s torrent, a family’s forge—urges us: In rage’s roar, wisdom whispers. But silence? That’s surrender. As she pens her next chapter, one truth burns bright: From ashes, phoenixes rise. And in her wings, perhaps, a nation’s redemption.

News

🏁 A Town Stopped in Its Tracks: Farewell to Dylan Commins, the 23-Year-Old Who Lived Life at Full Throttle 🚗💨

The bells of Our Lady of the Nativity had barely stopped tolling for Alan McCluskey on Thursday when they began…

He Planned Slowing Down at 50… Instead Life Handed Him a Positive Pregnancy Test!

In the sun-drenched hills of Surrey, where sprawling estates whisper of old money and new beginnings, Peter Andre lounges on…

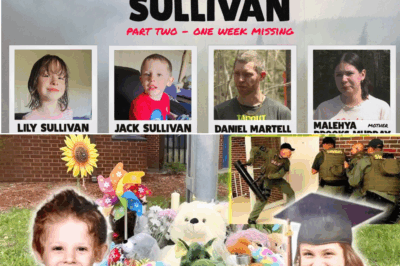

💔👀 Final Minutes on Camera: Two Children Seen Safe in Dollarama Before a 17-Hour Countdown to Disappearance

In the misty veil of Nova Scotia’s northeastern wilderness, where ancient pines whisper secrets to the wind and fog clings…

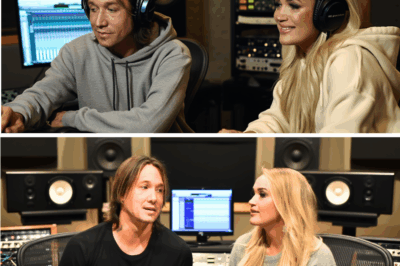

💌🎤 The Song Born from a 2 a.m. Text That Made 5 Million People Cry – How Keith & Carrie Made ‘The Fighter’ That Broke Hearts Worldwide 💔🌎

In the quiet hours of a Nashville night in late 2015, Keith Urban sat alone in his home studio, surrounded…

😭🎸 From Tribute to Heartbreak: How Keith Urban’s ‘Song for Dad’ Became the Anthem for Every Son Who Lost His Father 💔👨👦

In the vast tapestry of country music, where ballads of broken hearts and dusty roads often dominate the airwaves, few…

😭 Nashville Has Seen Legends But Nothing Like the Night Carrie Underwood and Vince Gill Sang ‘Go Rest High’ and Broke the World’s Heart 💔🎶

The 59th Annual Country Music Association Awards had already delivered every possible high: Lainey Wilson sobbing through her Entertainer of…

End of content

No more pages to load