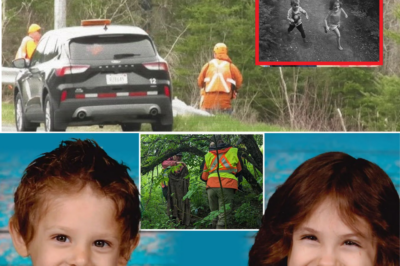

In the quiet, wooded expanse of Lansdowne Station, Nova Scotia, where the rustle of pine needles and the murmur of Gairloch Brook once promised solace, a grim discovery has shattered the illusion of rural tranquility. After 210 days of relentless searching, the remains of six-year-old Lilly Sullivan and her four-year-old brother, Jack, were unearthed near the brook’s mossy banks—a heartbreaking end to a case that gripped Canada and beyond. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), after meticulous forensic analysis, have ruled out accident or misadventure, officially classifying the case as a homicide investigation. The narrative that the siblings simply wandered from their Gairloch Road home, a story clung to by some in the early days, has crumbled. In its place, a darker truth emerges: one of family discord, a bitter custody battle, and questions of betrayal that point to those closest to the children. As the investigation pivots to uncover who silenced Lilly and Jack, the small community of Pictou County grapples with grief, suspicion, and the haunting realization that sanctuary can become a stage for tragedy.

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan on May 2, 2025, sparked an immediate and massive response. Reported missing by their mother, Malehya Brooks-Murray, at 10:01 a.m., the siblings were last seen at their trailer home on Gairloch Road, a sparsely populated stretch flanked by dense forest and winding creeks. The initial assumption—that the children, possibly autistic and known to roam, had strayed into the woods—mobilized over 160 searchers, including ground teams, K-9 units, drones, and helicopters. For six days, volunteers from Colchester, Pictou, and Halifax counties combed the rugged terrain, their neon vests a stark contrast to the somber greens of spring. The RCMP’s Northeast Nova Major Crime Unit took the helm, sifting through 860 tips, 8,060 video files, and interviews with over 60 individuals. Yet, despite the fervor, no trace of the children emerged, only fragments: a pink blanket confirmed as Lilly’s, found in a trash bag near the driveway; a size 11 boot print matching shoes Brooks-Murray purchased for Lilly at Walmart; a sock in the woods, its significance unclear.

As weeks turned to months, the case’s complexity deepened. Court documents, partially unsealed in August 2025 following a media challenge by The Canadian Press, The Globe and Mail, and CBC, revealed a tangle of leads and contradictions. Brooks-Murray and her partner, Daniel Martell, the children’s stepfather, told RCMP they were in bed with their infant, Meadow, on the morning of May 2, hearing Lilly and Jack playing in the kitchen. Security footage from a local Dollarama confirmed the family’s presence on May 1, but no independent verification placed the children at home after that afternoon. A witness reported seeing two children resembling Lilly and Jack walking north on Gairloch Road toward Westville around 9:30 a.m. on May 2, near a vehicle that appeared to be waiting—an account later deemed uncorroborated due to discrepancies in the children’s ages. Another tip, from a New Brunswick hotel employee, suggested the children’s biological father, Cody Sullivan, was seen with them, but Sullivan, estranged since October 2021, denied contact, claiming he was at home—his location redacted in reports.

The custody battle between Brooks-Murray and Sullivan loomed as a potential motive. Court records indicate a contentious separation, with Sullivan paying child support but barred from visitation due to prior disputes. Brooks-Murray speculated to police that Sullivan might have taken the children to New Brunswick, a theory unsupported by toll plaza videos or other evidence. Polygraph tests administered on May 12 to Brooks-Murray and Martell at the Bible Hill detachment yielded results described as “truthful” on specific, redacted questions, though an investigator noted the disappearance was not initially believed to be criminal. Sullivan and his mother, Belynda Gray, also took polygraphs, with no public disclosure of outcomes. Gray, the children’s paternal grandmother, became a vocal advocate, calling for a public inquiry and criticizing RCMP’s opacity, arguing that more transparency could refine public tips.

By September, the investigation took a somber turn. RCMP announced plans to deploy cadaver dogs, a move that signaled a shift from rescue to recovery. On September 25, two handlers and their dogs scoured Lansdowne Station, focusing on areas near Gairloch Brook, but found no human remains. A November search by the Ontario-based volunteer group Please Bring Me Home uncovered items—a child’s T-shirt, a blanket, a tricycle—but RCMP deemed them irrelevant. Public speculation, fueled by social media and true-crime forums, ran rampant: theories of abduction, accidental death, or foul play within the family clashed with official silence. “They’re complaining about crazy stories online,” Gray told Halifax City News on October 10. “Share more, and people can focus on what’s real.”

The breakthrough came on November 27, 2025, after an exhaustive 210-day effort. Acting on a new tip—details withheld to protect the investigation—RCMP forensic teams returned to Gairloch Brook, a shallow waterway weaving through hemlock groves less than a kilometer from the Sullivan home. There, beneath layers of silt and leaf litter, they uncovered skeletal remains, later identified through dental records and DNA as Lilly and Jack. The announcement, delivered by Staff Sergeant Rob McCamon at a somber press conference on November 29, stunned the nation. “This is a homicide investigation,” McCamon stated, his voice steady but grave. “We are pursuing all leads to determine the circumstances of these children’s deaths and bring those responsible to justice.” The ruling out of accidental causes—drowning, exposure, or wildlife—pointed to deliberate harm, thrusting the case into a new, chilling phase.

Lilly and Jack were more than names in headlines. Lilly, with her shoulder-length brown hair and pink boots, was a first-grader at West Pictou Consolidated, her classroom artwork—a rainbow-streaked unicorn—still pinned to a bulletin board. Teachers described her as curious, often asking about the stars during library hour, her suspected autism lending a quiet intensity to her focus. Jack, blond and wiry, was a preschooler with a love for dinosaurs, his blue dinosaur boots a gift from Brooks-Murray for his fourth birthday. “He’d roar like a T-Rex at recess,” a teacher recalled, her voice breaking in a CBC interview. Their lives, though brief, were woven into the fabric of Lansdowne Station—a community of 1,500 where neighbors swap garden vegetables and children bike down gravel lanes. The siblings’ absence left a void: a makeshift memorial outside the Stellarton RCMP detachment grew with teddy bears, candles, and handwritten notes reading, “Come home, little ones.”

The homicide declaration has shifted scrutiny to the family’s inner circle. Brooks-Murray, 28, and Martell, 31, remain central figures. Their accounts, while consistent, face renewed examination: both claimed to hear the children playing, yet no neighbors reported seeing them that morning. Martell’s actions post-disappearance—driving and running through the woods for hours—were documented, but gaps persist. The pink blanket, found in a trash bag, raises questions: was it discarded intentionally, or overlooked in panic? Forensic analysis, ongoing at RCMP’s Dartmouth lab, aims to clarify its role, alongside the boot print and sock. Brooks-Murray’s suggestion that Sullivan might be involved, coupled with her polygraph results, adds layers of complexity. Sullivan, 34, maintains he had no contact, his alibi under scrutiny despite no vehicle activity on Gairloch Road’s surveillance footage.

The custody battle provides a potential flashpoint. Court documents reveal Sullivan sought partial custody in 2020, a bid denied after allegations of domestic disputes, leaving Brooks-Murray as sole guardian. Gray’s insistence on Sullivan’s innocence—she told The Globe and Mail he “loved those kids”—clashes with Brooks-Murray’s early suspicions, hinting at unresolved tensions. RCMP’s refusal to name suspects, citing the investigation’s sensitivity, fuels speculation, but McCamon emphasized, “No one is cleared until we have answers.” Over 11 RCMP units, including the Behavioural Sciences Group and Criminal Analysis Service, are now involved, alongside the National Centre for Missing Persons and the Canadian Centre for Child Protection.

Pictou County, a region of rolling farmlands and fading industrial dreams, feels the weight of this loss acutely. At Dino’s Coffee Shop in New Glasgow, 30 kilometers south, locals debate over steaming mugs. “Those kids were everybody’s kids,” says Tom Hargrove, a retired millworker. “Now we’re wondering who we can trust.” Parents at West Pictou Consolidated have demanded enhanced school safety protocols, while churches like First Presbyterian host nightly vigils, their pews packed with mourners seeking solace. The economic ripple is subtle but real: tourism, a lifeline for the county’s craft fairs and coastal trails, has dipped, with visitors wary of a place now synonymous with tragedy.

The investigation’s scope is staggering. Over 800 tasks remain active, from re-interviewing witnesses to analyzing newly unsealed school bus footage. The RCMP’s Truth Verification Section is revisiting polygraph data, while digital forensics teams scour cloud backups for deleted files. A $150,000 reward, announced in June, still stands, urging anyone with information to call the Northeast Nova Major Crime Unit at 902-896-5060 or Nova Scotia Crime Stoppers at 1-800-222-TIPS. “We’re committed to certainty,” Cpl. Sandy Matharu, investigation lead, said in a June release. “This may take longer than hoped, but we won’t stop.”

For Lilly and Jack’s extended family, the pain is raw. Belynda Gray, speaking to Halifax City News, described the discovery as “a knife to the heart” but vowed to keep the children’s names alive. Brooks-Murray and Martell, sequestered in their trailer, have declined public comment since August, their attorney citing emotional distress. Sullivan, reached by The Canadian Press, offered only, “I just want justice for my babies.” Community efforts persist: a GoFundMe for a memorial playground has raised $20,000, and West Pictou plans a spring assembly in the siblings’ honor, with students planting a maple tree for each child.

The broader implications of this case ripple beyond Nova Scotia. It underscores the vulnerabilities of rural communities, where isolation can mask danger, and the complexities of missing persons cases involving children with special needs. Advocacy groups like Autism Canada are pushing for mandatory wander-prevention training in schools, citing Lilly and Jack’s possible autism as a factor in their initial framing as runaways. The RCMP’s redaction of key details, while standard to protect leads, has drawn criticism from transparency advocates, who argue public trust hinges on openness. Meanwhile, true-crime platforms—podcasts like “Vanished in the Valley” and Reddit threads—dissect every unsealed document, risking misinformation but keeping pressure on authorities.

As winter descends on Lansdowne Station, Gairloch Brook flows quietly, its waters a mirror to a community’s sorrow. The pines stand sentinel, their branches heavy with frost, guarding secrets yet to be fully revealed. Lilly and Jack, once the heart of a trailer filled with laughter and dinosaur roars, are gone, their lives stolen in an act the RCMP now calls deliberate. The question of who betrayed their sanctuary—mother, stepfather, father, or another shadow—hangs like fog over Pictou County. For now, the investigation presses on, fueled by a nation’s demand for answers and a family’s plea for closure. In the silence of the woods, the truth is surfacing, one painful fragment at a time, promising justice for two children whose light was extinguished too soon.

News

Vince Gill’s ‘Look at Us’ Proves the Most Powerful Love Stories Aren’t Loud—They’re Built in Silence, Patience, Forgiveness, and the Courage to Stay 💛🌾

There is a moment in every long marriage when the romance novels and the wedding vows and the breathless first-kiss…

🚨 5️⃣ 210 Days, Two Children Lost, One Still Alive: The Heartbreaking Turn in Lilly and Jack’s Case That Shook All of Canada 💔🇨🇦

In the quiet, wooded expanse of Lansdowne Station, Nova Scotia, where the rustle of pine needles and the murmur of…

🌲 4️⃣ What Happened in Those Woods? Lilly and Jack Found De@d Near Gairloch Brook—One Child Still Fighting for Life as Homicide Detectives Close In” 😢🔍

In the quiet, wooded expanse of Lansdowne Station, Nova Scotia, where the rustle of pine needles and the murmur of…

🚨🌊 Tragic Morning at Kylies Beach: Young Swiss Swimmer Killed by Bull Shark While Her Injured Boyfriend Battles to Survive After Dragging Her to Shore 😢🌅

The golden light of an Australian dawn painted the horizon in hues of pink and orange, casting a serene glow…

🏊♀️🦈 What Began as a Sunrise Swim With Dolphins Ended in Tragedy When a Bull Shark Targeted Swiss Tourist Livia Mühlheim, Leaving Her Partner Injured While Trying to Save Her

The golden light of an Australian dawn painted the horizon in hues of pink and orange, casting a serene glow…

Bailey Turner Faces Cameras, Crowds, and Crushing Uncertainty as His Father Remains Missing in the Jefferson National Forest — A Community Watches a Young Coach Carry the Weight of a Family’s Crisis 🏈🔥

The rolling hills of Southwest Virginia, where Friday night football lights pierce the autumn dusk like beacons of hope, have…

End of content

No more pages to load