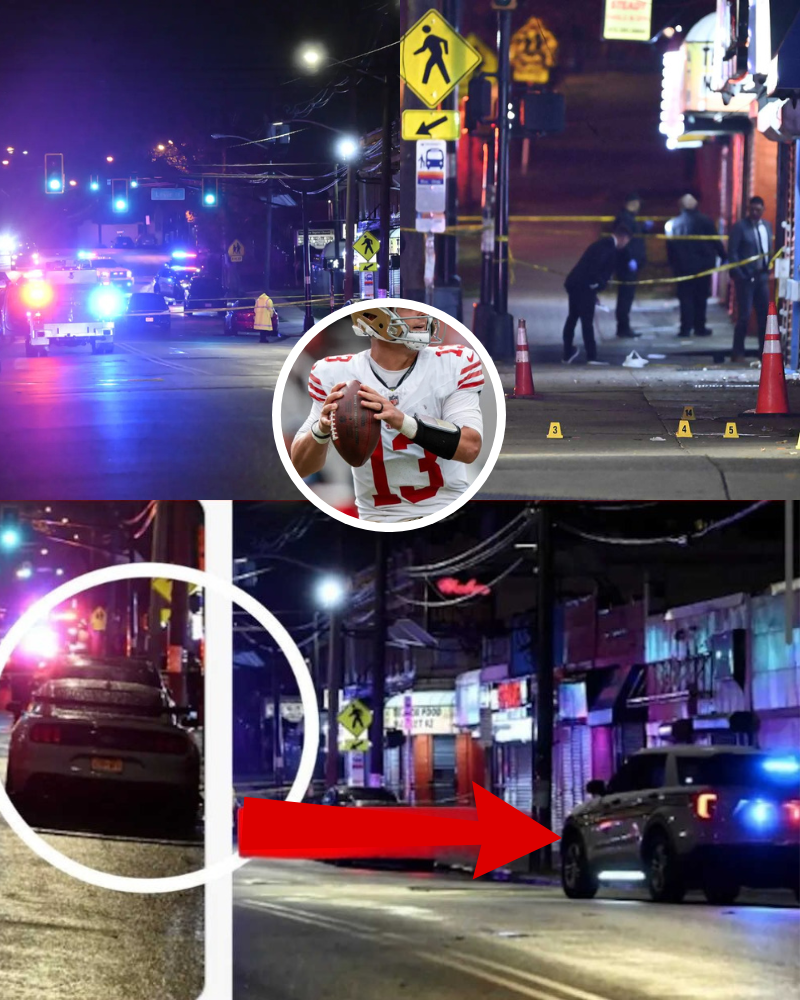

A vibrant 10-year-old football enthusiast, Jermaine Garcia, was laid to rest in the hearts of his Newark community after a hail of gunfire claimed his young life on November 15, 2025. The budding athlete, known for his lightning-quick feet and infectious smile on the field for the West Ward Hawks youth team, was one of two fatalities in a chaotic shooting at the intersection of Chancellor Avenue and Leslie Street in Newark’s South Ward. His 11-year-old brother, walking alongside him after practice at a Lyons Avenue recreation center, was among three others wounded but is now reported in stable condition. “They were good kids,” their longtime coach Kenneth Luckey told NJ Advance Media on Sunday, his voice cracking as he described the brothers’ dedication to the sport that kept them off the streets. “As far as I know, they got caught up in the middle of some kind of crossfire shootout.” The incident, which also claimed the life of 21-year-old woman Tiana Reynolds and injured a 19-year-old man and a 60-year-old man, has left Newark reeling, prompting an anti-gun violence rally and vows of relentless pursuit from city leaders.

The shooting unfolded around 7:45 p.m. Saturday, transforming a bustling corner near storefronts and apartment buildings into a scene of panic. Witnesses described hearing a barrage of at least a dozen shots, with bystanders diving for cover behind parked cars and fleeing into nearby businesses. Jermaine and his brother, fresh from a team session where they dreamed of high school grids and beyond, were simply heading home when the bullets flew. A 12-year-old teammate had been walking with them moments earlier but peeled off just before the chaos, Luckey recounted, crediting a guardian angel for sparing one more life. The Garcia brothers, inseparable on and off the field, had joined the Hawks two years prior, channeling their energy into drills and camaraderie. Jermaine, a pint-sized running back with dreams of NFL glory, often stayed late for extra reps, his coach said. “He lit up the practices—always encouraging his teammates, never backing down from a tackle.” The 11-year-old, equally spirited, idolized his big brother and now faces a long road of physical therapy and emotional healing at University Hospital.

Newark Public Safety Director Brian O’Hara detailed the grim toll in a Sunday briefing: The 10-year-old succumbed to multiple gunshot wounds shortly after arrival at the ER, while Reynolds, a local barista and single mother, fought valiantly but passed in the early hours of Sunday. The surviving victims—a 19-year-old with leg injuries, the 60-year-old grazed in the arm, and the younger Garcia boy with a shoulder wound—were all stabilized, thanks to swift paramedic response. Ballistics recovered from the scene suggest at least two shooters, with shell casings scattered like confetti from a weapon possibly chambered in 9mm, per preliminary forensics. No arrests have been made, but Essex County Prosecutor Ted Stephens announced a $25,000 reward for tips leading to convictions, urging the public to come forward via the anonymous hotline at 1-877-TIPS-4EC.

Mayor Ras Baraka, visibly shaken during a presser outside City Hall, labeled November 15 a “dark and devastating day in Newark.” The tragedy compounded an already sorrowful weekend, following the accidental death of a 2-year-old who fell from a 20th-floor window earlier that afternoon. “We will not rest until there is justice for the parents and families left behind in unspeakable pain and grief,” Baraka declared, flanked by faith leaders and youth advocates. “Newark will work tirelessly with the prosecutor’s office, state law enforcement, and federal agencies to ensure justice is served. We urge the perpetrators to turn themselves in, as there is no safe place to hide.” Baraka’s words echoed a familiar refrain in a city that’s seen homicides drop 30% year-over-year under his administration—down to 68 as of November—but where stray bullets still claim innocents too often.

The South Ward, a vibrant mosaic of working-class families and immigrant enclaves, has long grappled with spillover from gang disputes in neighboring areas. Community policing data from the Newark PD shows a 15% uptick in drive-by incidents in the past quarter, often tied to narcotics turf wars involving out-of-state crews. Yet, residents like barber Tony Ramirez, who knew the Garcias from his shop, reject the narrative of inevitability. “These boys weren’t in that life—they were in cleats, not colors,” Ramirez told CBS New York, wiping away tears as he swept clippings. “Jermaine wanted to be like Saquon Barkley; his brother tagged along for the snacks. This ain’t right.”

Tributes poured in swiftly. The West Ward Hawks canceled practices, holding a candlelight vigil Sunday night at the rec center where the boys last laughed. Teammates donned Garcia’s No. 22 jersey for a makeshift memorial, while a GoFundMe launched by Luckey had raised $45,000 by Monday morning for funeral costs and the brother’s medical bills. “Help us honor Jermaine’s spirit—keep our kids on the field, not in the ground,” the page read, sharing photos of the siblings in full gear, mud-streaked and grinning after a muddy scrimmage. Newark’s NFL alumni chapter, led by ex-Giant Carl Banks, pledged $10,000 and mentorship for the team, vowing to expand after-school programs. Faith communities mobilized too: Rev. Jamal Bryant of Word of Faith International led prayers at the site, calling it “a clarion call to dismantle the pipelines of pain.”

The rally against gun violence, drawing 500 souls to Military Park by dusk Sunday, amplified the urgency. Organized by Mothers Against Murder and Mayhem, speakers from the NAACP and local mosques decried the “epidemic of easy access,” pointing to New Jersey’s strict laws undercut by ghost guns smuggled from lax states. “One child’s dream deferred is a community’s nightmare,” intoned organizer Keisha James, holding a sign reading “No More Jermaines.” Chants of “Justice Now” mingled with calls for federal intervention, echoing Baraka’s push for ATF task forces in high-risk zones.

Broader context paints a stark picture. Newark’s youth gun violence, while down from 2013 peaks, still claims lives at a rate triple the national average for kids under 15, per CDC data. The Essex County Prosecutor’s office has ramped up youth diversion programs since 2023, funneling at-risk teens into sports and trades, but gaps persist: Only 40% of South Ward rec centers are fully staffed post-pandemic. Experts like Rutgers criminologist Nora Demleitner argue for holistic fixes—mental health embeds in schools, economic boosters like job pipelines—but warn that reactive policing alone breeds distrust. “These shootings aren’t isolated; they’re symptoms of disinvestment,” Demleitner said in a Monday op-ed for The Star-Ledger.

For the Garcia family—parents Maria and Luis, Newark natives who’ve scraped by on factory shifts—the loss defies metrics. Maria, speaking through tears to SILive reporters outside the hospital, clutched a team photo: “He was my light, always saying ‘Mom, watch this run.’ Now the house is quiet.” Luis, a former semi-pro player himself, vowed to channel grief into advocacy, joining Baraka’s community safety council. The 11-year-old brother, bandaged but buoyant, reportedly asked for his helmet upon waking: “Gotta get back to practice—for J.”

As investigators canvas surveillance from corner delis and canvass neighbors, Newark holds its breath. Ballistic matches to prior unsolved cases could crack open a network, but for now, the focus is healing. Sunday’s rally ended with a huddle—Hawks players linking arms, coaches leading a silent cheer. In a city forged in resilience, Jermaine’s memory becomes a playbook: Run toward light, tackle darkness together. “Good kids like him remind us why we fight,” Luckey said, helmet in hand. “For every yard gained, for every life saved.” Justice may come slow, but Newark’s resolve? Unbreakable.

News

Season 6 of Emily in Paris takes the glossy Netflix hit far from its postcard-perfect Parisian streets and drops it into the blazing sun of Greece, where romance feels intoxicating, jealousy simmers just beneath the surface, and every unresolved emotion threatens to explode.

Emily said yes — and the world around her immediately began to crack. Season 6 of Emily in Paris takes…

Old Money Season 2 Confirmed: The Dynasty Returns With Bigger Scandals, Deeper Betrayals, and a New War for Power

The highly anticipated follow-up to one of the most talked-about dramas of last year is officially on its way. Old…

Stefon Diggs Breaks Social Media Silence With Clear Message to Cardi B After Birthday Post for Wave and Blossom

After an extended period of silence on social media, Stefon Diggs resurfaced with a message that immediately captured public attention….

Blue Ivy Approaches a Major Milestone Next Year: She Will Be the Same Age Beyoncé Was When Her Music Career Began

A unique and symbolic milestone is approaching for the Carter family, one that has caught the attention of fans, entertainment…

Rick Ross’ Unexpected Gift to Lil Wayne Sparks Online Speculation After Revealing the Rapper Doesn’t Have a Driver’s License

An unexpected and headline-grabbing moment erupted across social media after Rick Ross presented Lil Wayne with a brand-new BMW i7,…

A Resurfaced Moment Between Cardi B’s Daughter Kulture and Blossom Belles Captures Attention Again

A brief but memorable interaction between Cardi B’s daughter Kulture and the Blossom Belles has resurfaced online, drawing renewed attention…

End of content

No more pages to load