In the sweltering heat of Tanzania’s Gombe Stream National Park, a 26-year-old Jane Goodall arrived in July 1960, armed with little more than boundless curiosity, a notebook, and her indomitable spirit. Back home in England, her dreams of studying wild chimpanzees had been met with skepticism and outright mockery. “A secretary turned scientist? In the African bush?” the naysayers scoffed. Women weren’t meant for such rugged pursuits, they said, and primates were mere brutes, not worthy of deep observation. Funded meagerly by paleontologist Louis Leakey, Goodall set up camp in isolation, her mother Vanne as her sole companion, facing financial strains that left her rationing tinned food and dreaming of bananas she couldn’t afford.

For months, Goodall endured a grueling routine: rising before dawn, trekking through dense forest undergrowth, binoculars slung over her shoulder, only to be met with fleeing shadows. The chimpanzees, Gombe’s elusive residents, sensed her intrusion and vanished like ghosts, keeping a 500-yard buffer that mocked her every effort. Loneliness gnawed at her—letters from home were her lifeline, and the jungle’s symphony of hoots and rustles often blurred into haunting silence. Hunger was a constant shadow; she foraged what she could, her slight frame growing leaner under the equatorial sun. Yet Goodall persisted, sketching behaviors from afar, naming the distant figures in her mind to humanize them: the alpha Goliath, the gentle matriarch Flo, and one particularly striking male with a silvery chin beard she dubbed David Greybeard.

Then, in a moment that would echo through scientific annals, the unthinkable unfolded on November 4, 1960. After weeks of patient offerings—palm nuts and overripe fruit left as peace gestures—David Greybeard approached. No longer fleeing, he accepted a red palm nut from her hand, his dark eyes locking with hers in a gaze of tentative trust. It was the crack in the wall. David, with his calm demeanor and reassuring hugs to frightened young chimps, became her bridge to the troop. He led others closer, his presence signaling safety. Goodall watched, heart pounding, as he ventured into her camp, rifling through tents for hidden treats, his elongated hands dangling in relaxed curiosity.

But David’s true legacy emerged from a termite mound. Goodall witnessed him select a blade of grass, insert it into the earth, and deftly extract wriggling insects—a rudimentary tool use that shattered the dogma of human uniqueness. “Now we must redefine tool, redefine Man, or accept chimpanzees as humans,” Leakey famously wired back. Soon, Goliath joined, stripping leaves from twigs to fashion better probes, revealing not just intelligence but innovation in these “wild” beings. Goodall’s observations snowballed: chimps hunted bushpigs and colobus monkeys, devouring meat with relish, debunking vegetarian myths; they formed complex social bonds, waged territorial wars, and displayed profound emotions—grief, joy, even cannibalism in darker times like the polio epidemics that ravaged the community.

David Greybeard passed in 1968, likely from pneumonia, but his imprint endures. Gombe’s Kasakela community thrives, their behaviors cataloged in one of the longest-running wildlife studies ever. Sixty years later, in the same sun-dappled forests, researchers note descendants—grandchildren and great-grandchildren of David’s lineage—bearing names like Fanni or Freud, still habituated to human observers. They groom under canopies where Goodall once sat, their calls a living echo of that pivotal trust. Goodall’s work birthed the Jane Goodall Institute in 1977, safeguarding habitats and empowering youth through Roots & Shoots, now spanning over 100 countries.

Her story transcends science: it’s a testament to empathy’s power. Ridiculed and resource-starved, Goodall proved that patience and respect could unlock worlds. In an era of environmental peril, her legacy whispers through the trees—reminding us that every individual, human or chimp, counts in the grand tapestry of life. As Gombe’s chimps swing into tomorrow, they carry her name on the wind, a quiet homage to the woman who saw them first as equals.

News

Chilling Dashcam Horror: Empty Boat of Missing Lawyer Randall Spivey and Nephew Drifts 75 Miles – Device Pinpoints Location as Nearby Cam Captures Terrifying Scene! 😱

In a baffling case that has gripped Southwest Florida, prominent attorney Randall “Randy” Spivey, 57, and his nephew Brandon Billmaier,…

Heartbreaking Gulf Mystery: Coast Guard Halts Epic Search for Vanished Lawyers – Foul Play or Tragic Accident Lurking Beneath the Waves?

In a chilling development that has gripped Southwest Florida, the U.S. Coast Guard announced the suspension of its extensive search…

Heart-Wrenching Final Scream: Eyewitnesses Haunted Forever by Renee Nicole Good’s Agonizing Cry Before ICE Agent Fatally Shoots Her in Minneapolis

The woman gunned down by an ICE agent in Minneapolis has been identified as 37-year-old Renee Nicole Good, who described herself as…

Heartbreaking Final Promise: Newlywed Lawyer’s Last Dinner with Wife Before Vanishing on Doomed Fishing Trip with Uncle 💔🌊

In a devastating turn of events that has gripped communities in Florida and beyond, 33-year-old attorney Brandon Billmaier and his…

Miracle in the Gulf: Divers Return with Shocking Good News After Days Searching for Missing Randy and Grandson Brandon! 😲🌊

In a stunning turn of events that has captivated the nation, a team of dedicated divers has brought back extraordinary…

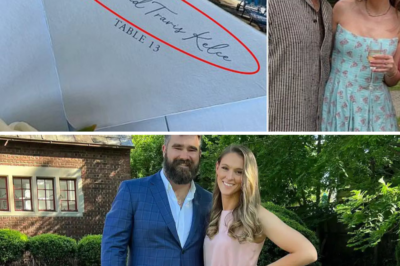

Kylie Kelce Finally Unveils Taylor Swift & Travis Kelce’s Dreamy Wedding Invitation – And It’s Even More Magical Than Fans Imagined! ✨

In the latest episode of her popular podcast, Kylie Kelce delighted fans worldwide by sharing a long-awaited glimpse into one…

End of content

No more pages to load