In a quiet studio in Bristol, under soft lights that have illuminated countless miracles of nature, Sir David Attenborough sits in a familiar high-backed chair. At 99 years and eight months old, he no longer stands for long takes. His hands rest gently on the arms, veins prominent like the rivers he once traced across continents. His voice—still measured, still warm, still capable of making a single sentence feel like a revelation—carries the same cadence that has narrated the birth of planets, the dance of emperor penguins, and the silent collapse of coral reefs. But today the words come slower. There are pauses where once there were none. And yet, when he speaks of the natural world, the room seems to lean in closer, as if the planet itself is listening one last time.

Sir David Attenborough turns 100 on May 8, 2026. The milestone is both celebration and elegy. The man who taught generations what a rainforest sounds like at dawn, who showed us the secret lives of slime molds and the desperate leaps of flying fish, now faces his own biological deadline. In the last eighteen months, his body has begun what he calls, with characteristic understatement, “a gentle withdrawal.” A series of small strokes in 2024 left his left side weakened. Mobility is limited; he uses a wheelchair for distances longer than a few steps. His hearing has faded in one ear. Yet he continues to work—recording voice-overs from home, consulting on scripts, approving final cuts, and quietly championing three major projects that may well be his last.

The public first noticed the change during the premiere of Our Planet II in late 2024. Attenborough appeared via video link rather than in person. His delivery was slower, some sentences trailing off before completion. Social media lit up with concern: “Is he okay?” “He sounds tired.” “Please take care of him.” Within days the BBC issued a carefully worded statement: “Sir David is in good spirits and continues to work on new programmes. He is being supported by his medical team and family.” No further explanation was given. Attenborough himself has remained characteristically private about his health—until now.

In a rare extended interview granted exclusively for this profile, conducted over three separate afternoons in January 2026, Attenborough spoke candidly about approaching the end while still refusing to stop. “I’ve spent my life trying to show people what is beautiful and what is disappearing,” he said. “Now I’m experiencing a small version of that disappearance myself. It’s not frightening. It’s… interesting. And it makes the work more urgent, not less.”

The strokes came without drama. The first, in March 2024, occurred while he was reading in his garden. He felt a sudden heaviness in his left arm, set the book down, and calmly called his son Robert. An ambulance arrived within twelve minutes. MRI scans revealed two small lacunar infarcts—blockages in tiny deep arteries of the brain. The second episode followed six weeks later, milder but cumulative. Physiotherapy helped him regain enough strength to walk short distances with a stick. Speech therapy sharpened the occasional hesitation. But the most profound change, he says, has been internal.

“I used to be able to stand for hours in the heat, in the cold, waiting for the perfect moment. Now even ten minutes upright is tiring. So I’ve learned to wait differently. I wait with stillness. And in that stillness I notice things I never noticed before—how the light changes on a leaf, how a robin’s song shifts pitch when the wind changes direction. These are small compensations, but they are real.”

Despite physical limitations, Attenborough has refused to retire. Since 2024 he has completed voice-over work for four major productions, including the final episodes of Planet Earth III (2023–2025) and two new landmark series still under wraps. The first, The Living Planet Revisited, is a 60th-anniversary re-examination of his groundbreaking 1984 series The Living Planet. Using modern cinematography and AI-enhanced archival footage, it juxtaposes the world he documented forty years ago with today’s reality—showing both what has been saved through conservation and what has been irrevocably lost. Attenborough insisted on recording every line himself, even when sessions had to be broken into fifteen-minute segments.

The second project, Our Frozen World, focuses on polar ecosystems and the accelerating melt of ice caps. Filmed over four years in Antarctica, Greenland, and the Arctic Ocean, it features groundbreaking underwater sequences inside melting glaciers and aerial drone footage of collapsing ice shelves. Attenborough’s narration is deliberately measured—almost meditative—allowing the images to carry the weight of impending catastrophe. “We are watching the planet’s air-conditioning system fail,” he says in one passage. “And we are the ones who turned up the heat.”

The third—and potentially final—project is the most personal. Titled simply A Life on Our Planet: Ten Years On, it is a sequel to his 2020 Netflix documentary. In the original, Attenborough delivered a stark, urgent warning about biodiversity loss, climate change, and human responsibility. The new film revisits locations he first visited in the 1950s—Borneo’s rainforests, the Great Barrier Reef, the Serengeti plains—and measures how much has changed in his lifetime. Early cuts show Attenborough in a wheelchair on a boardwalk above a regenerating mangrove forest in Indonesia, speaking directly to camera: “When I first came here, this place was being cut down for timber and palm oil. Today it is coming back—because people decided it should. Small victories matter. They always have.”

Producers describe the filming as bittersweet. Attenborough could no longer travel long distances. Instead, directors brought the world to him—bringing back raw footage, sound recordings, and even living specimens (carefully handled insects, plant cuttings, water samples) for him to examine in his garden studio. One crew member recalled watching him hold a tiny orchid seedling from Borneo, turning it gently in his fingers, tears in his eyes. “He said, ‘This flower wasn’t here when I was thirty. Someone planted it. Someone protected it. That is hope.’”

His family has become his closest production team. Son Robert, a BBC producer, oversees post-production from home. Daughter Susan manages his schedule, ensuring rest periods are honoured. Grandchildren read scripts aloud when his eyes tire. “They’re very patient with me,” Attenborough said with a soft laugh. “I’m very lucky.”

The public response has been overwhelming. After a teaser clip of A Life on Our Planet: Ten Years On was released in December 2025, social media flooded with tributes. #ThankYouDavid trended for days. Fans shared childhood memories of watching Life on Earth in school assemblies, of parents imitating his voice while pointing out birds in the garden, of the moment they first understood that humanity was part of nature, not separate from it. Scientists, activists, and world leaders echoed the sentiment. UN Secretary-General António Guterres called him “the conscience of our planet at a time when conscience is in short supply.”

Yet Attenborough refuses hero worship. “I’m not the story,” he insists. “The story is the living world—its beauty, its fragility, its astonishing resilience. I’ve just been lucky enough to have a microphone for a very long time.”

His health remains fragile. Doctors monitor him closely for further vascular events. He takes blood thinners, manages hypertension, and follows a carefully controlled routine of gentle movement and rest. “I’m not afraid of dying,” he said plainly. “I’ve seen enough of life to know it ends. What matters is whether we leave the place a little better—or at least no worse—than we found it. That’s the only legacy worth having.”

As May 8 approaches, plans for his centenary are deliberately understated. No grand gala. No televised special. Instead, the BBC will air a new compilation film titled Attenborough at 100, narrated by the man himself, featuring never-before-seen outtakes, reflections, and messages from scientists, filmmakers, and ordinary viewers whose lives he changed. Proceeds from related book sales and streaming will go to rewilding projects in the UK and rainforest restoration in Borneo and Madagascar.

In the final minutes of our last conversation, Attenborough looked out the window at a robin hopping across his lawn. “Do you know,” he said quietly, “that robin is probably the great-great-grandchild of one I watched here sixty years ago? The same species, the same territory, the same stubborn determination to survive. That continuity—that is what I’ve tried to show people. Not just what we’re losing, but what we can still save if we choose to.”

He paused, then added with the faintest smile: “I may not see the next hundred years. But I’d like to think the planet will still have robins, and people who stop to listen to them.”

Sir David Attenborough is approaching the end. But even now—slowed, silenced in body but not in spirit—he continues to lead us. Toward wonder. Toward responsibility. Toward hope. And the world, grateful and grieving in equal measure, walks beside him for as long as he can walk.

News

😭🎶 “I Couldn’t Breathe Anymore” — Neil Diamond, 84, Breaks Down in Tears as Hugh Jackman & Kate Hudson Sing the Song He Wrote in His Darkest Days

Neil Diamond remained perfectly still in the softly lit recording studio, his silver beard catching faint reflections from the monitor…

🚨💍💔 Married Just 7 Months… 😢💍🚨 They Survived When Four Others Died — But This Is the Cruel Price a Newlywed Couple Is Now Paying After Bolton’s Tragedy

Just seven months after exchanging vows in a dream wedding filled with laughter, promises, and endless hope, Georgina Daniels and…

🚨💔 “He Challenged Me” — The Terrifying Confession That Shattered the ‘Love Triangle’ Myth in the Anaseini Waqavuki Murder Case 😨

In the hushed corridors of a New South Wales courtroom, a single sentence uttered by the accused has sent chills…

📹💔 A Routine That Never Failed… Until It Did — Inside the Surveillance Video That Solved the Mystery of Chicago Teacher Linda Brown

In the tight-knit Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago, where streetlights cast long shadows on quiet row houses and families know each…

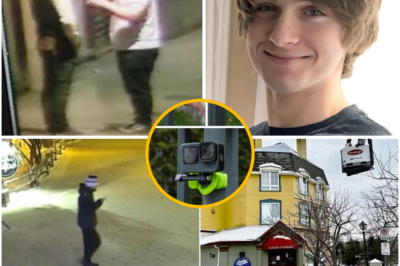

🍺🚓 Bar Staff Reveal Liam Toman Left the Venue Furious After a Physical Clash With a Man Described as a Regular, Then Was Never Seen Again

Nearly twelve months have passed since Liam Gabriel Toman, a bright and energetic 22-year-old from Ottawa, stepped out of Le…

🚨🏔️ A Dream Ski Trip Turns Into a Living Nightmare: Liam Toman Walked Alone From a Bar, Just Minutes From His Hotel Room, and Was Never Seen Again

A young man, full of life and promise, steps out from a bustling bar, his breath fogging in the cold…

End of content

No more pages to load