The words still echo in the minds of those who heard them firsthand: “I can’t believe they would do that.” Spoken in a voice thick with disbelief and anger, they came from a longtime resident of K’gari’s eastern beachfront, a man who has walked the same sands for decades and knows every tide, every dune, every shadow cast by the island’s infamous dingoes. On a quiet afternoon in late January 2026, he handed Queensland Police a grainy but unmistakable video clip captured on his phone—footage that has abruptly shifted the narrative surrounding the tragic death of 19-year-old Canadian backpacker Piper James, turning what many assumed was a straightforward if heartbreaking wildlife incident into something far more complex, controversial, and deeply unsettling.

Piper James, a bright-eyed young woman from Campbell River, British Columbia, had arrived in Australia the previous November, embarking on what her family described as “the trip of her life.” She was six months into an adventure across the continent, volunteering at a hostel near the iconic Maheno shipwreck on K’gari—once called Fraser Island, now restored to its Butchulla name meaning “paradise.” The World Heritage-listed island, with its endless white-sand beaches, turquoise lakes, and wild rainforests, draws hundreds of thousands of tourists each year. But it is also home to one of the purest populations of dingoes in Australia—wild canids that roam freely, often in packs, and whose interactions with humans have long been a source of tension.

In the early hours of January 19, 2026, Piper ventured alone onto Seventy-Five Mile Beach for a morning swim. The sun was barely above the horizon when she entered the water around 5 a.m. Ninety minutes later, two passersby driving along the beach made a horrific discovery: her body lay near the water’s edge, surrounded by a pack of approximately 10 dingoes. Police arrived quickly, securing the scene as the animals lingered nearby. Initial reports spoke of bite marks visible on her limbs and torso; rangers monitored the pack, noting aggressive behavior. The news spread rapidly worldwide—a young tourist, alone on a remote beach, apparently mauled by dingoes in what would be the first fatal adult dingo-related death on the island in decades.

Preliminary autopsy findings, released by the Coroners Court of Queensland on January 23, complicated the picture. “Physical evidence consistent with drowning” dominated the report, alongside “injuries consistent with dingo bites.” Crucially, coronial spokespeople clarified that pre-mortem bite marks—those inflicted while Piper was still alive—were “unlikely to have caused immediate death,” while extensive post-mortem bites suggested the dingoes had scavenged her body after she perished. Drowning emerged as the leading cause, possibly triggered by panic, rip currents, exhaustion, or a desperate attempt to escape perceived threats in the surf.

Yet the story refused to settle. Queensland authorities, citing ongoing “aggressive behavior” from the involved pack, announced the euthanasia of at least six dingoes, with more targeted in the days that followed. The decision ignited fierce backlash: animal conservation groups decried it as knee-jerk punishment of native wildlife; Butchulla traditional owners expressed heartbreak over not being consulted; online forums erupted with debates about human encroachment versus animal rights. “It’s their home,” one commenter wrote. “People ignore signs, feed them, run from them—then blame the dingoes when things go wrong.”

Then came the video.

The resident—whose identity police have protected for safety—approached officers after days of soul-searching. He had been reviewing footage from his security camera setup overlooking the beach when something caught his eye: a clip timestamped shortly before Piper’s swim. In the dim pre-dawn light, figures move near the waterline. The video, now in police hands and partially described in media briefings, shows what appears to be two or more people interacting with dingoes in a way that deviates sharply from standard tourist behavior. Gestures suggest deliberate provocation—throwing objects, approaching too closely, even what one source called “taunting motions.” The resident’s stunned reaction—“I can’t believe they would do that”—stemmed from recognizing behaviors he had witnessed sporadically over years but never captured so clearly.

Queensland Police have confirmed receipt of the footage and its integration into the ongoing investigation. “This material introduces new lines of inquiry,” a spokesperson stated cautiously in late January. “We are examining timestamps, enhancing clarity where possible, and cross-referencing with witness statements, autopsy details, and other evidence.” No arrests have been made, and authorities stress the inquiry remains open, exploring all possibilities—including accident, misadventure, and any potential human involvement.

The revelation has electrified public discourse. Was Piper targeted or harassed in some way that escalated her peril? Did unseen individuals contribute to a chain of events leading to her drowning? Or is the video merely contextual—showing routine (if irresponsible) human-dingo interactions common on K’gari, where feeding bans are frequently ignored? Skeptics point to the island’s history: dingoes here are habituated to people, drawn by food scraps, and quick to approach lone figures. Signs everywhere warn visitors: “Never run,” “Stay in groups,” “Don’t feed wildlife.” Yet violations persist.

Piper’s family, devastated, has spoken sparingly. Her parents described a vibrant, adventurous daughter who loved nature and had been warned about dingoes but perhaps underestimated the risks. Friends recall her excitement about volunteering near the Maheno wreck, posting photos of sunrises and rainforest trails. “She was living her dream,” one said. Now, the family plans to visit Australia, seeking closure amid swirling questions.

The video’s emergence has also reignited broader debates about K’gari’s management. Calls grow louder for stricter visitor controls—limited access, mandatory guides in high-risk zones, harsher penalties for feeding or provoking dingoes. Conservationists argue culling solves nothing long-term; education and habitat protection do. Others insist human safety must come first after repeated incidents: the 2001 fatal mauling of nine-year-old Clinton Gage, the 2023 attack on a jogger driven into the surf, countless lesser encounters.

As February 2026 unfolds, the beach where Piper James met her end lies quieter under summer skies. Rangers patrol more visibly; signs multiply; tourists tread carefully. The pack involved has been reduced, but dingoes remain—silhouettes on dunes at dawn, eyes reflecting headlights at night. The new video evidence hangs like a shadow over the tragedy, promising answers yet delivering only more questions.

What really happened in those final minutes on Seventy-Five Mile Beach? Did Piper drown alone, overwhelmed by waves and fear? Or did something—or someone—push events toward an irreversible end? The resident’s footage, born of disbelief, may hold the key. Until forensic enhancements, witness corroboration, and full police disclosure arrive, the island keeps its secrets. Paradise, after all, has always had sharp edges.

In the end, Piper James came seeking wonder and found peril. Her story, now twisted by this unexpected twist, reminds the world that on K’gari, nature and humanity collide in ways no one can fully predict—or control. The search for truth continues, one frame at a time.

News

😱 “I Knew Something Was Wrong” — Silence Finally Broken 🔎 Grandmother Exposes Disturbing Details in Lilly and Jack Sullivan Disappearance

The silence that has shrouded the disappearance of six-year-old Lilly Sullivan and her four-year-old brother Jack since May 2, 2025,…

💔 Second 16-Year-Old Girl Dies After Frisco Sledding Crash, Turning a Snow Day Joyride Into a Heartbreaking Wake-Up Call for Parents Everywhere

Gracie Brito fought for her life for days, tethered to machines in an intensive care unit while machines breathed for…

Tragic Final Hours Revealed 🚨💔 Comedy Legend Catherine O’Hara Passes Away at 71, Just Hours After Medical Emergency

The sudden and heartbreaking loss of Catherine O’Hara on January 30, 2026, sent shockwaves through the entertainment world and beyond….

💔 “Our Light” — Grieving Parents of Canadian Teen Piper James Make a Heartbreaking Journey Back to the Island Where She Died

The parents of Canadian backpacker Piper James have made a heartwrenching announcement. In the wake of unimaginable loss, Angela and…

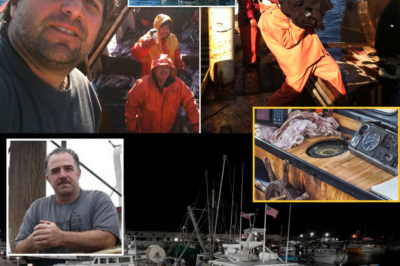

Before the Search Was Halted, a Friend Heard the Captain’s Last Call—Now Those Words Haunt a Community After the Boat Sank off Massachusetts ⚓💔

In the unforgiving expanse of the North Atlantic, where winter storms rage like ancient beasts and the line between survival…

The Ocean Took Them Without Warning: Coast Guard Ends Search for the Lily Jean as Families Face Unthinkable Loss 🖤🌊

Coast Guard Suspends Search for Crew of Gloucester Fishing Vessel Lily Jean After Tragic Sinking GLOUCESTER, Mass. — The U.S….

End of content

No more pages to load