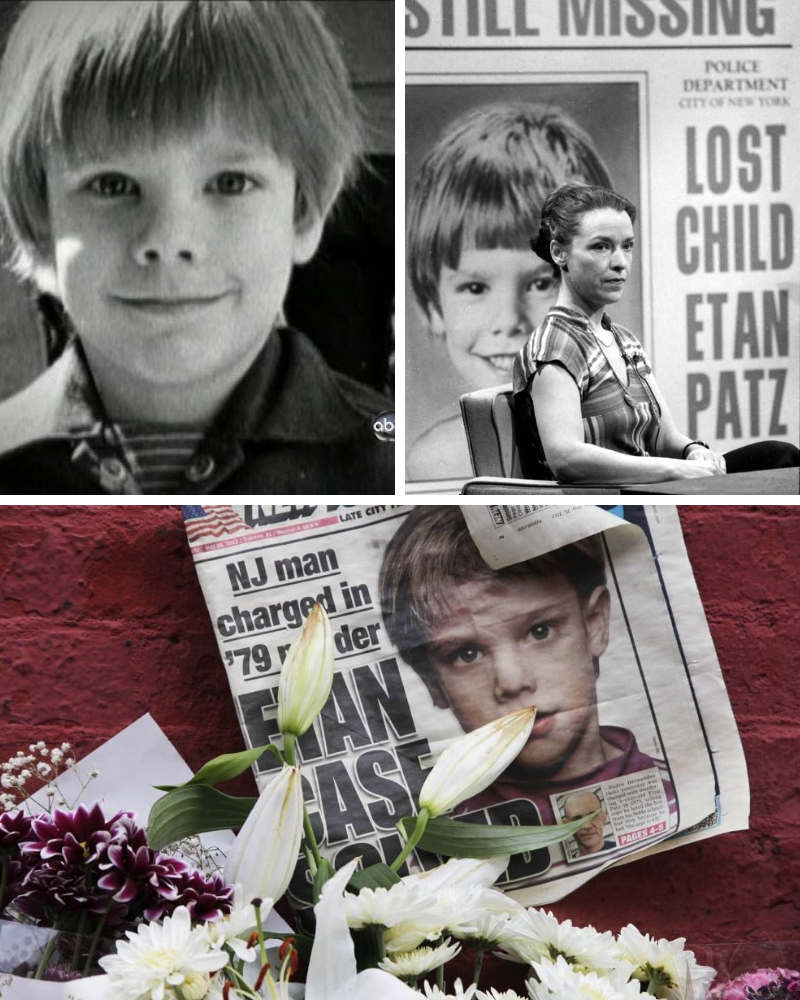

Today marks what would have been Etan Patz’s 53rd birthday, a somber milestone in one of the most haunting child disappearance cases in American history. The six-year-old boy vanished on May 25, 1979, while walking alone for the first time to his school bus stop in Manhattan’s SoHo neighborhood. His case not only captivated the nation but also revolutionized how missing children are searched for and remembered. Yet, more than four decades later, justice remains elusive. In July 2025, a federal appeals court overturned the conviction of Pedro Hernandez, the man found guilty of Etan’s kidnapping and murder, citing errors in jury instructions. Now, as of October 2025, a judge has given prosecutors until June 1, 2026, to retry the case or release Hernandez, reigniting debates over confessions, mental health, and the pursuit of closure in cold cases.

Etan Kalil Patz was born on October 9, 1972, to Stanley and Julie Patz, a professional photographer and his wife living in a vibrant but gritty SoHo loft at 113 Prince Street. On that fateful Friday morning in 1979, Etan begged his parents to let him walk the two short blocks to the bus stop at West Broadway and Prince Street by himself—a rite of passage for the independent kindergartener. Dressed in a black “Future Flight Captain” pilot cap, blue corduroy jacket, blue jeans, and blue sneakers with fluorescent stripes, he carried a dollar to buy a soda at the corner bodega. He left around 8 a.m., but never made it to school. His teacher noted his absence but didn’t alert authorities immediately, assuming a family mix-up. By afternoon, Julie Patz grew worried and called the police after checking with neighbors and the school.

The response was swift but chaotic in an era before coordinated missing-child protocols. Nearly 100 officers and bloodhounds scoured the area that evening, interviewing residents and searching rooftops, alleys, and sewers. Posters with Etan’s photo—taken by his father—blanketed the city, even projecting onto buildings in Times Square. Despite the frenzy, no solid leads emerged. Detectives briefly eyed the parents as suspects, a common practice then, but quickly cleared them. As days turned to weeks, the case faded from headlines, but the Patz family refused to let it die. Stanley Patz would later send annual missing posters to a key suspect with the chilling note: “What did you do to my little boy?”

Etan’s disappearance became a catalyst for change. In the early 1980s, his image was among the first to appear on milk cartons as part of a nationwide campaign to raise awareness about missing children. This effort, spearheaded by organizations like the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (founded in 1984), helped locate hundreds of kids. President Ronald Reagan declared May 25— the anniversary of Etan’s vanishing—National Missing Children’s Day in 1983. The case also influenced legislation, including the Missing Children’s Assistance Act, which established federal resources for investigations. Experts credit Etan’s story with shifting public perception from viewing child abductions as rare to recognizing them as a pervasive threat, prompting parents nationwide to tighten supervision.

For years, the investigation focused on Jose Ramos, a convicted child molester and drifter who dated one of Etan’s former babysitters. Ramos lived nearby and had a history of luring boys into drainpipes and other secluded spots. In 1982, several children accused him of attempted abductions, and police found photos of Ramos with young boys resembling Etan. Assistant U.S. Attorney Stuart GraBois took over in 1985 and zeroed in on Ramos, who was already in prison for unrelated child molestation charges. During a 1990 interrogation, Ramos admitted to taking a boy matching Etan’s description to his apartment for sex on the day of the disappearance, claiming he was “90 percent sure” it was Etan and that he put the child on a subway afterward. A jailhouse informant in 1991 corroborated this, saying Ramos confessed details and even drew a map of Etan’s bus route.

Ramos became the prime suspect, featured in media reports like a 1999 New York Post article. In 2001, Etan was declared legally dead in absentia. The Patz family sued Ramos for wrongful death in 2004, winning a $2 million default judgment when he refused to testify. Ramos denied killing Etan and was never criminally charged in the case. He was released from prison in 2012 after 20 years but rearrested for violating sex offender registry laws. Interestingly, the Patz family later dismissed the judgment against Ramos in 2016, convinced by new evidence that he wasn’t responsible.

The case took a dramatic turn in 2010 when Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. reopened it. In April 2012, authorities excavated a basement at 127B Prince Street—a former handyman’s workshop near the Patz home—but found no evidence. Then, on May 24, 2012—the eve of the 33rd anniversary—Pedro Hernandez, a 51-year-old former bodega clerk from New Jersey, was arrested after confessing to the crime. Hernandez, who was 18 in 1979 and worked at a bodega on Prince Street, told investigators he lured Etan into the basement with the promise of a soda, strangled him, stuffed his body in a box, and dumped it in a nearby trash heap. The tip came from Hernandez’s brother-in-law, Jose Lopez, who contacted authorities after hearing family rumors. Hernandez’s sister and a church group leader also recalled him confessing in the 1980s.

Hernandez was indicted on second-degree murder and first-degree kidnapping charges in November 2012 and pleaded not guilty. His defense argued the confession was false, coerced after seven hours of interrogation without initial Miranda warnings, and influenced by his low IQ (around 70) and schizotypal personality disorder, which could cause hallucinations. A pre-trial hearing in 2014 ruled the statements admissible. The first trial began in January 2015 and ended in a mistrial in May after a hung jury (11-1 for conviction). A retrial started in October 2016, with prosecutors relying heavily on the videotaped confessions and witness testimonies. After nine days of deliberations, the jury convicted Hernandez on February 14, 2017. He was sentenced to 25 years to life on April 18, 2017.

A state appellate court affirmed the conviction in March 2020. But Hernandez’s legal team persisted, and on July 21, 2025, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit overturned it. The panel ruled that the trial judge erred in responding to a jury question during deliberations. Jurors asked if finding the initial un-Mirandized confession involuntary required disregarding subsequent ones; the judge simply said “no” without elaboration, which the appeals court deemed a violation of federal law and tainting the verdict.

In October 2025, U.S. District Judge Colleen McMahon in Manhattan set a firm deadline: Jury selection for a third trial must begin by June 1, 2026, or Hernandez must be released. Prosecutors from DA Alvin Bragg’s office requested more time—90 days to decide on retrying and a year to prepare—citing the challenge of locating over 50 witnesses from the 2017 trial. They also plan to petition the U.S. Supreme Court to review the Second Circuit’s decision, potentially restoring the conviction. Judge McMahon rejected delaying based on speculative Supreme Court action, emphasizing the need for resolution in this 46-year-old case. Hernandez’s attorney, Harvey Fishbein, argued against a third trial, noting his client’s 13 years in prison, lack of prior criminal history, and the emotional toll on all involved.

The implications are profound. If no retrial occurs, Hernandez—now 64—could walk free, leaving Etan’s family without closure. Stanley Patz, now in his 80s, has expressed mixed feelings in past interviews, prioritizing truth over vengeance. The case highlights ongoing issues in the justice system, including the reliability of confessions from individuals with mental health challenges and the balance between victims’ rights and defendants’ protections. Critics argue the lack of physical evidence—Etan’s body was never found—makes the case reliant on potentially flawed statements.

Etan’s legacy endures beyond the courtroom. His story inspired safer streets initiatives, Amber Alerts, and heightened parental vigilance. Annual vigils on May 25 draw advocates, and organizations like the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children credit him with saving lives. As one expert noted, “Etan changed how America protects its children.” But with the case unresolved, it serves as a stark reminder that some mysteries persist, fueling speculation on social media and true-crime podcasts. Prosecutors face mounting pressure: retry a frail defendant in a decades-old case or risk public backlash for letting a possible killer go free.

As winter approaches in 2025, the Patz family and the nation watch closely. Will the Supreme Court intervene? Will a third trial bring finality? For now, Etan’s birthday passes as another chapter in an unfinished story, a testament to enduring grief and the quest for answers in the face of uncertainty.

News

Rihanna Responds to a Fan Saying, “They Saying It’s 2016, Rih”: What Her Viral Reply Really Means

When a fan recently commented, “They saying it’s 2016, Rih,” few expected Rihanna to respond. She often ignores random online…

Rihanna’s Unmatched Face Card: How One Look Became a Cultural Phenomenon

Few celebrities command attention the way Rihanna does. Across red carpets, candid street photographs, and unfiltered social media moments, one…

400,000 FRANCS FOR RELEASE: PROSECUTORS SEEK BAIL FOR OWNERS AFTER DEADLY CRANS-MONTANA NEW YEAR FIRE

Prosecutors in Sion have requested a total of 400,000 Swiss francs in bail to grant provisional freedom to Jacques and…

📰 RCMP RELEASES NEW TIMELINE DETAILS IN LILLY AND JACK SULLIVAN CASE AS ALLEGED MESSAGES SPARK FRESH CLAIMS

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has entered another sensitive phase as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police released new…

JUST NOW: Investigators Flag Timeline Issues and Re-Examine Key Details in the Disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has taken an unexpected and unsettling turn, according to the latest update released…

A new wave of controversy erupted online this week after the daughter of an NBA legend reportedly came forward with what she described as troubling information involving Stefon Diggs and his relationship with Cardi B.

According to circulating social-media claims, she suggested that Cardi B should reconsider her involvement with the NFL star, citing alleged…

End of content

No more pages to load