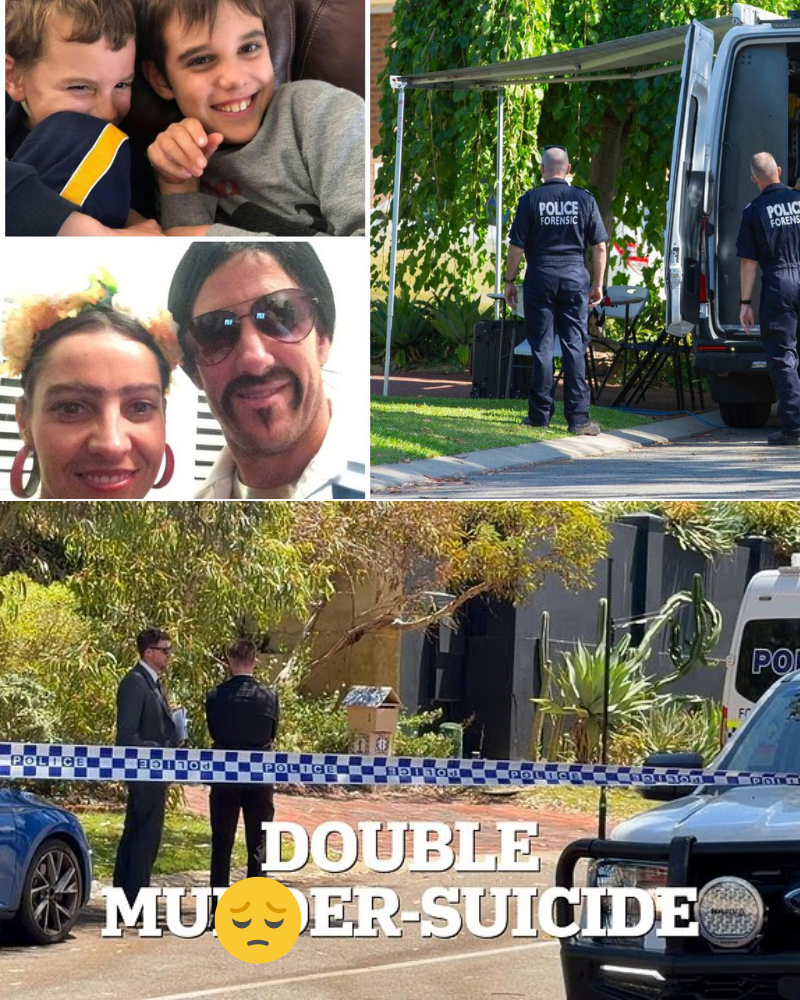

The quiet, leafy streets of Mosman Park, one of Perth’s most affluent suburbs, are rarely associated with the sirens of emergency vehicles or the grim yellow tape of a double-homicide investigation. Known for its river views and multi-million dollar estates, the area serves as a symbol of stability and success. However, the recent deaths of Otis and Leon Clune—two young brothers living with profound disabilities—have shattered that image, replaced by a national debate over the adequacy of Australia’s social safety net.

As the community grapples with the immediate trauma of the event, the focus has shifted from the shock of the crime to the complexities of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS). The tragedy has raised a harrowing question: How did a family seemingly surrounded by resources fall into such a catastrophic state of neglect and despair?

The Events at Mosman Park

In the early hours of the morning, police were called to the Clune residence, where they discovered the bodies of Otis and Leon. Their father was taken into custody and subsequently charged. While the legal proceedings are ongoing and the principle of “innocent until proven guilty” remains paramount, the public discourse has moved rapidly toward the environment in which these children lived.

Otis and Leon were not typical children. They suffered from rare, severe neurological conditions that necessitated 24-hour medical supervision. They were non-verbal, required specialized feeding equipment, and were entirely dependent on caregivers for every aspect of their existence. Neighbors described the family as “private” and “devoted,” yet the pressure of managing two high-needs children in a domestic setting is a burden few can truly comprehend.

The NDIS: A Promise Under Pressure

The National Disability Insurance Scheme was launched in 2013 with a vision of “choice and control” for Australians living with disabilities. It was designed to move away from a block-funded welfare model to an individualized insurance model. On paper, the Clune family should have been the primary beneficiaries of this world-class system. Reports suggest the family had access to significant funding—potentially totaling hundreds of thousands of dollars annually.

However, the tragedy has highlighted a glaring disconnect between funding and function. Advocacy groups argue that having an NDIS plan is not the same as having support. The “market-based” model of the NDIS assumes that if a family has the money, they can simply purchase the services they need. In reality, the disability sector is currently facing a dire workforce shortage.

“You can have a million dollars in your NDIS account,” says one local disability advocate, speaking on the condition of anonymity, “but if there are no nurses available to work the night shift, or if the agencies are tied up in administrative ‘red tape,’ that money is just numbers on a screen. It doesn’t change the fact that a mother or father is staying awake for 48 hours straight to keep their children alive.”

The “Red Tape” and Bureaucratic Fatigue

Central to the criticism following the Mosman Park deaths is the bureaucratic burden placed on families. To access and maintain NDIS funding, parents must act as de facto project managers, accountants, and advocates. This requires navigating a labyrinth of audits, plan reviews, and evidence-gathering.

For a family already pushed to the brink by the physical and emotional demands of caregiving, the “administrative load” can be the final straw. In the case of the Clune family, reports have emerged of ongoing struggles to secure consistent, high-level nursing care. When a scheduled carer fails to show up—a common occurrence in the current labor market—the responsibility falls entirely back on the parents. This creates a “pressure cooker” environment where there is no respite and no exit strategy.

The Myth of the “Affluent Safety Net”

One of the most striking aspects of this case is its location. Mosman Park is an area of immense private wealth. This has led to a broader sociological discussion regarding the “invisibility” of disability in affluent circles. There is often a societal assumption that if a family is wealthy, they “must be fine.”

However, professional caregivers argue that disability is a great equalizer. The medical needs of children like Otis and Leon transcend social class. Private wealth cannot always buy the specialized medical equipment or the highly trained pediatric nurses required for such complex cases, especially when the national supply is exhausted. The isolation felt by the Clune family suggests that even in a wealthy neighborhood, a family can become an island if the formal systems of support fail to integrate with the community.

The Mental Health of Caregivers

While the investigation into the father’s motives continues, psychologists are pointing to the phenomenon of “caregiver burnout” or “compassion fatigue” at an extreme level. When a caregiver is deprived of sleep, socially isolated, and navigating a failing support system, their cognitive function and emotional regulation can deteriorate.

This is not to provide a legal excuse for violence, but to provide a context for the “crisis point” that many disability families face. The Australian government has been urged to include more robust mental health screenings and mandatory respite periods for primary caregivers of “high-complexity” participants. Currently, the NDIS focuses primarily on the participant (the child), often overlooking the health and stability of the support unit (the parents).

Political and Institutional Response

In the wake of the tragedy, the Federal Minister for the NDIS has expressed condolences but defended the scheme’s overall structure, noting that thousands of families are supported successfully every day. Nevertheless, a formal review into the specific handling of the Clune family’s case is expected.

Critics, including the Opposition and minor parties, have used the event to call for an overhaul of the NDIS’s “Plan Management” system. They argue that the system has become too focused on preventing fraud and cutting costs, and has lost sight of the “human element.” There are calls for “High-Intensity Case Managers” who could intervene when a family shows signs of systemic collapse.

Community Tributes and the Path Forward

The gates of the Mosman Park home have been adorned with flowers, teddy bears, and letters of grief. The local primary school and disability support groups have held vigils, remembering Otis and Leon not as “cases” or “statistics,” but as two boys who loved music, the feeling of the sun, and the presence of their family.

The legacy of this tragedy will likely be measured in policy change. If the NDIS is to fulfill its original promise, it must address the “thin markets” in caregiving and reduce the bureaucratic hurdles that exhaust the very people it aims to help.

Conclusion

The Mosman Park tragedy is a multi-layered failure. It is a failure of a father to protect his children, but it is also potentially a failure of a multi-billion dollar system to recognize a family in freefall. As the legal system seeks justice for Otis and Leon, the political system must seek a way to ensure that “choice and control” does not turn into “isolation and abandonment.”

Justice for the Clune brothers involves more than a courtroom verdict; it involves a fundamental shift in how Australia supports its most vulnerable citizens and those who care for them. The silence in the Mosman Park house today is a haunting reminder that in the absence of a functional system, even the most affluent surroundings cannot prevent a tragedy.

News

Rihanna’s Viral “House-Price Coat” and the Luxury Fashion Moment That Took Over the Internet

When Rihanna steps out for what she casually calls a “simple dinner,” the internet knows it is anything but simple….

Old Money Season 2 Delivers a Power Shift, Broken Alliances, and a Secret Pregnancy That Could Rewrite an Entire Dynasty

The second season of Old Money has dramatically escalated the series’ ongoing battles for control, influence, and family dominance. While…

“Mortimer Beaufort Is Not the Villain: An Unfiltered Look at One of Maxton Hall’s Most Misunderstood Characters”

In the world of Maxton Hall, few characters spark as much debate as Mortimer Beaufort. From the moment he appears…

Maxton Hall Season 3 Trailer Reveals the Beaufort Lie and a High-Stakes Fight for Redemption

The official trailer for Maxton Hall Season 3 (2026) has dropped, delivering an intense preview of what appears to be…

New Scene From My Life with the Walter Boys Season 3 Reveals a Turning Point for Jackie, Alex, and the Series’ Central Love Triangle

A newly released scene from My Life with the Walter Boys Season 3 has captured widespread attention across social platforms,…

XO, Kitty Season 3 Trailer Teases a Sobering Turning Point as the Dream Comes to an End

The official trailer for XO, Kitty Season 3 has been released, offering a dramatic and emotionally grounded preview of what…

End of content

No more pages to load