In a startling archaeological find that sheds light on ancient human practices, researchers have uncovered modified human bones dating back approximately 5,000 years in eastern China. The artifacts, which include skull cups and mask-like facial structures, were discovered amid discarded remains in canals and moats at Neolithic sites. This discovery, detailed in a recent study, marks the first evidence of such systematic bone modification in the region’s Liangzhu culture, raising questions about how urbanization may have influenced perceptions of the dead.

The bones were exhumed from five key sites in the Yangtze River Delta, primarily Zhongjiagang, with additional finds at Bianjiashan, Putaofan, Meirendi, and Huoxitang. These locations, part of the Liangzhu culture that flourished between 5300 and 4500 years before present (BP), are known for their advanced urban features, including elaborate water management systems, jade artifacts, and stratified cemeteries. Unlike formal burials found elsewhere in Liangzhu sites—such as the elite tombs at Fanshan and Yaoshan—these modified bones were scattered among pottery shards and animal remains, suggesting they were treated as refuse rather than revered objects.

Lead researcher Junmei Sawada, a biological anthropologist at Niigata University of Health and Welfare in Japan, explained in the study that the modifications appear to have been carried out after the bodies had decomposed naturally. There were no signs of violent death, such as cut marks from conflict or dismemberment, indicating the bones were collected post-mortem for crafting. “The fact that many of the worked human bones were unfinished and discarded in canals suggests a lack of reverence toward the dead,” Sawada noted. This contrasts sharply with earlier Neolithic traditions in the region, where human remains were typically buried intact and with care.

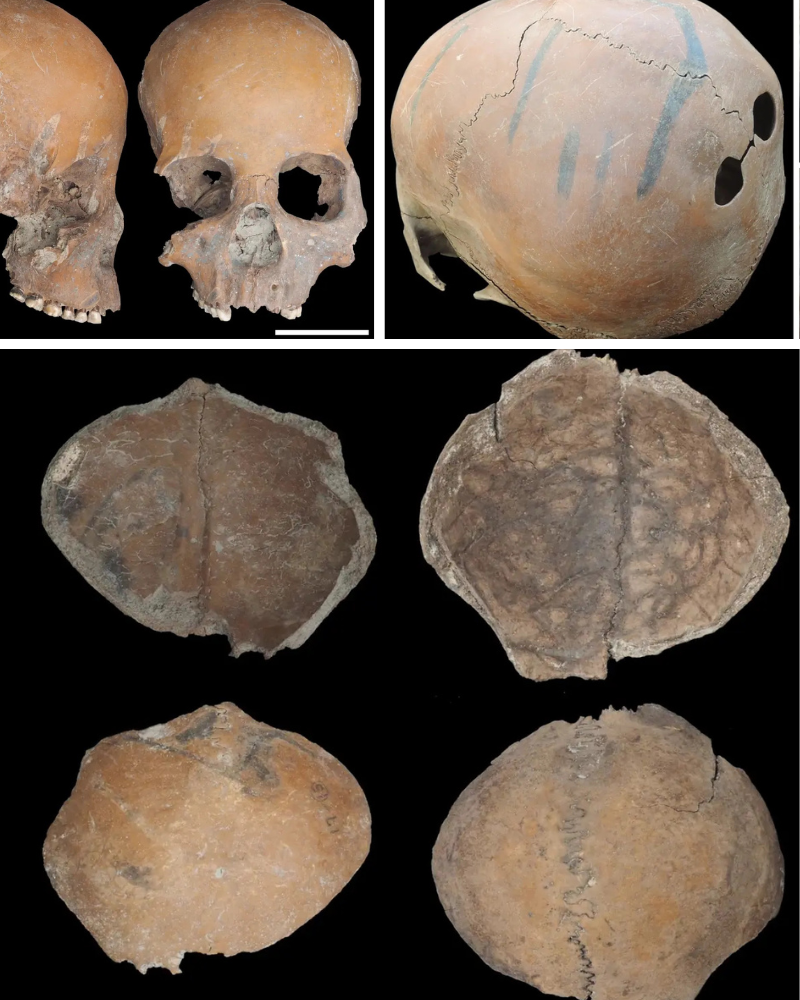

Out of 183 human bones examined, 52 showed clear evidence of human intervention, including splitting, grinding, perforating, and polishing. The most common modifications were to skulls, which accounted for about 71% of the worked specimens. Researchers classified the artifacts into several types:

Skull Cups (Type A): Four adult craniums were sliced or split horizontally to form cup-like vessels. Some featured polished rims, indicating they were finished products, while others remained incomplete. Similar skull cups have been found in high-status Liangzhu burials at sites like Fuquanshan in Shanghai and Jiangzhuang in Jiangsu, hinting at possible ritual or prestige uses.

Mask-Like Facial Skulls (Type B): Another four skulls were severed vertically, creating eerie, mask-shaped pieces that evoke modern depictions of “Day of the Dead” imagery. These were mostly unfinished, with rough edges suggesting they were prototypes or abandoned midway through production.

Plate-Shaped Skull Fragments (Type C): Twenty-one small, flat pieces of cranial bone, likely failed attempts at larger items, were ground down but left incomplete.

Perforated Child’s Skull (Type D): A single skull from a child aged 6 to 8 years old featured holes drilled into the back, possibly for attachment or display purposes. This finished piece stands out as one of the few completed artifacts among the discards.

Flattened Mandibles (Type E): Three lower jawbones—one from an adolescent and two from adults—had their bases ground flat, perhaps for use as tools or ornaments.

Modified Limb Bones (Type F): Twelve long bones from arms and legs, including humeri, femurs, and tibias, showed ends that were narrowed, transected, or fractured. Some subtypes appeared designed for practical utility, like handles, while others were clearly unfinished.

The remaining seven bones were miscellaneous remnants, further emphasizing the experimental or utilitarian nature of the work. Radiocarbon dating placed the modifications primarily between 4800 and 4600 cal BP, a period spanning roughly 200 to 400 years during the middle to late Liangzhu phase. This timeframe coincides with environmental challenges, such as reduced precipitation and the decline of the culture’s hydraulic systems, which may have influenced social dynamics.

Experts believe the practice reflects a profound shift in how the Liangzhu people viewed human remains. Elizabeth Berger, a bioarchaeologist at the University of California, Riverside, who was not involved in the study, commented, “The most interesting and unique thing about the findings is the fact that these worked human bones were essentially trash.” She agreed with the researchers’ hypothesis that urbanization played a key role. As Liangzhu society grew into one of East Asia’s earliest urban centers—with populations in the tens of thousands and complex hierarchies—traditional kinship ties may have weakened. “The people of Liangzhu came to see some human bodies as inert raw material,” Berger added, suggesting that bones from non-kin, low-status individuals, or even outsiders were repurposed without the emotional attachments seen in smaller, community-based societies.

This interpretation draws on broader anthropological patterns. In other prehistoric cultures, modified human bones often carried symbolic weight tied to ancestry, warfare, or ritual. For instance, Pleistocene-era skull tools in Europe or Neolithic skull cups in West Asia were frequently associated with veneration or trophies. In contrast, the Liangzhu examples lack such context; their discard in waterways implies a more pragmatic approach, possibly driven by the anonymity of urban life. “We suspect that the emergence of urban society—and the resulting encounters with social ‘others’ beyond traditional communities—may hold the key to understanding this phenomenon,” Sawada stated.

The study’s methods involved detailed osteoarchaeological analysis, including microscopic examination of tool marks and paleopathological assessments. No significant differences were found in age, sex, or health indicators between worked and non-worked bones, though worked specimens showed a slightly higher proportion of females and skulls. Conditions like cribra orbitalia (a sign of anemia) and linear enamel hypoplasias (indicating childhood stress) appeared in both groups, pointing to overall societal hardships rather than targeted selection.

Why did this practice emerge suddenly and vanish after a few centuries? Researchers speculate it was tied to Liangzhu’s rapid urbanization and subsequent decline around 4300 BP, possibly due to flooding or climate shifts. The culture, recognized by UNESCO as a testament to early Chinese civilization, featured monumental architecture and sophisticated craftsmanship in jade and pottery. Yet, this bone-working tradition stands alone in Neolithic China—no similar modifications have been found in predecessor cultures like Hemudu or Majiabang, nor in contemporaries elsewhere in the Yangtze Delta.

Future research could provide more clarity. Isotopic analysis and DNA testing on the bones might reveal the origins of the individuals—whether they were locals, migrants, or from lower social strata. Such data could confirm if the “others” hypothesis holds, illustrating how growing cities fostered detachment from the dead. As Berger pondered, “What caused that to happen and why did it only last for a few centuries?”

This discovery not only highlights the macabre ingenuity of ancient peoples but also offers a window into the social transformations that accompanied the birth of urban life. In an era when modern societies grapple with similar issues of anonymity and resource use, the Liangzhu artifacts serve as a grim reminder of how cultural norms evolve under pressure. As excavations continue in the region, more secrets from this enigmatic culture may yet surface, piecing together the puzzle of humanity’s distant past.

News

Rihanna Responds to a Fan Saying, “They Saying It’s 2016, Rih”: What Her Viral Reply Really Means

When a fan recently commented, “They saying it’s 2016, Rih,” few expected Rihanna to respond. She often ignores random online…

Rihanna’s Unmatched Face Card: How One Look Became a Cultural Phenomenon

Few celebrities command attention the way Rihanna does. Across red carpets, candid street photographs, and unfiltered social media moments, one…

400,000 FRANCS FOR RELEASE: PROSECUTORS SEEK BAIL FOR OWNERS AFTER DEADLY CRANS-MONTANA NEW YEAR FIRE

Prosecutors in Sion have requested a total of 400,000 Swiss francs in bail to grant provisional freedom to Jacques and…

📰 RCMP RELEASES NEW TIMELINE DETAILS IN LILLY AND JACK SULLIVAN CASE AS ALLEGED MESSAGES SPARK FRESH CLAIMS

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has entered another sensitive phase as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police released new…

JUST NOW: Investigators Flag Timeline Issues and Re-Examine Key Details in the Disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has taken an unexpected and unsettling turn, according to the latest update released…

A new wave of controversy erupted online this week after the daughter of an NBA legend reportedly came forward with what she described as troubling information involving Stefon Diggs and his relationship with Cardi B.

According to circulating social-media claims, she suggested that Cardi B should reconsider her involvement with the NFL star, citing alleged…

End of content

No more pages to load