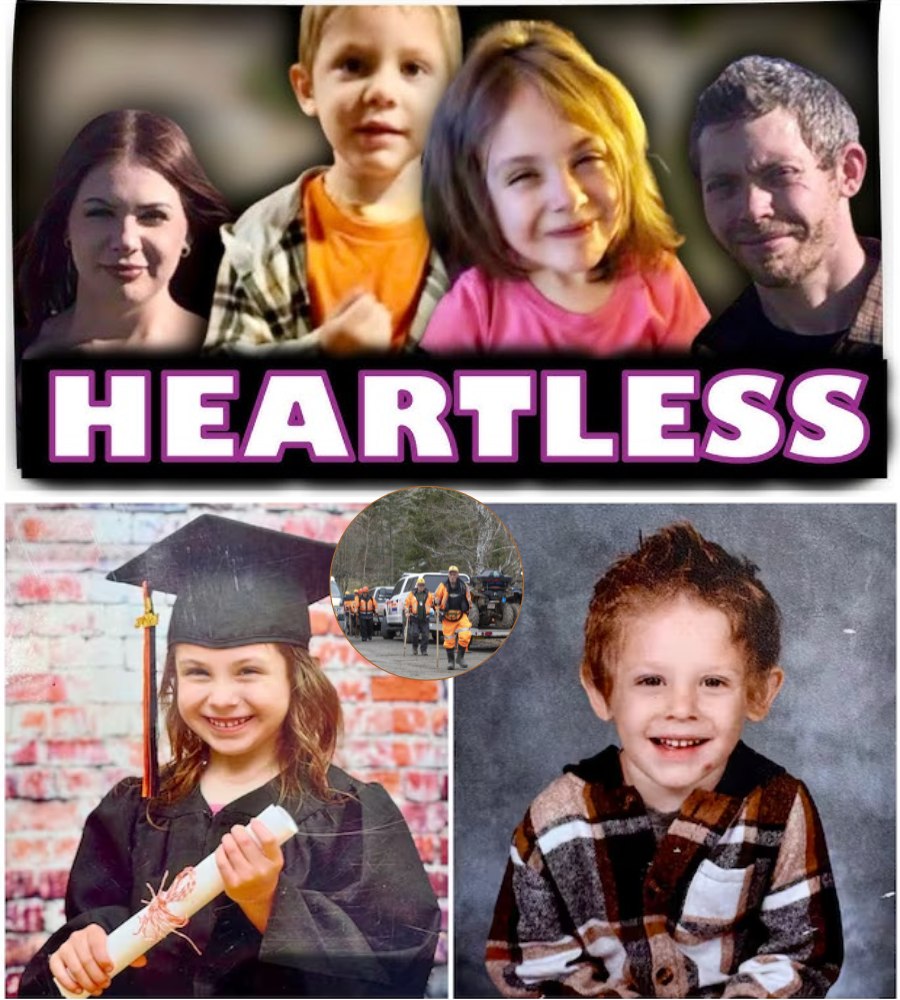

🚨 BREAKING: Family of missing Lilly & Jack just got CAUGHT physically ATTACKING volunteers searching for the kids… and then called 911 to SHUT IT DOWN.

Six months. Two tiny children gone. And the second volunteers finally hit the Middle River, Daniel Martell’s own relatives charged in — screaming, shoving, threatening — desperate to stop anyone from digging on PUBLIC land.

They found a child’s shirt. A blanket scrap. A tricycle piece. Then the family showed up and everything stopped.

Why are they terrified of what’s in that river? What exactly don’t they want the world to see?

The full story is absolutely chilling — the fights, the 911 call, the items police now say “don’t matter”… and the one question everyone is asking: If the kids really just wandered off, why is this family willing to fight tooth and nail to keep that river untouched?

Tap the link. You need to see this.

In a case that has gripped the nation for six agonizing months, the disappearance of 6-year-old Lilly Sullivan and her 5-year-old brother Jack from their rural family home has taken a dramatic and contentious turn. Volunteers scouring the banks of the Middle River of Pictou last weekend were met not with cooperation, but with outright hostility from relatives of the children’s stepfather, Daniel Martell. Reports of shoving, verbal assaults, and even a 911 call to halt the search on public land have ignited fresh outrage and speculation, raising pointed questions about what the family might be desperate to conceal. As the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) downplay the incident and insist the case remains active, the confrontation underscores deep rifts within the Sullivan-Martell family and a community weary of unanswered pleas for transparency.

The siblings were last seen at their family’s cluttered trailer on Gairloch Road in Lansdowne Station, a remote speck in Pictou County about 140 kilometers northeast of Halifax. On the morning of May 2, 2025, their mother, Malehya Brooks-Murray, placed a frantic 911 call around 10 a.m., reporting that the children had wandered away from the property while she and Martell tended to their 1-year-old daughter, Meadow. The home, surrounded by dense woods, steep riverbanks, and thick underbrush, backs onto the Middle River—a waterway known for its swift currents and hidden dangers. Lilly, described by family as a bright-eyed girl fond of her strawberry-patterned backpack, was likely wearing a pink sweater, pants, and boots. Jack, her dinosaur-obsessed little brother, sported blue dino-themed footwear and carried a beloved blanket.

Martell, 34, a mill worker on stress leave since the incident, has maintained that the children slipped out a silent sliding back door undetected. “We could hear Jackie in the kitchen,” he recounted to reporters in the chaotic days following the disappearance. “A few minutes later, we didn’t hear them, so I went out to check. The sliding door was closed. Their boots were gone.” Brooks-Murray echoed the account, noting the children had been kept home from Salt Springs Elementary School the previous two days due to Lilly’s cough. Surveillance footage from a New Glasgow Dollarama on May 1 at 2:25 p.m. captured the entire family—Martell, Brooks-Murray, Meadow, Lilly, and Jack—shopping together, marking the last independently verified sighting of the siblings.

What followed was a massive, five-day ground search involving over 130 personnel, helicopters, drones, and cadaver dogs. The effort yielded scant clues: a child’s boot print near the property edge, a torn piece of pink blanket (confirmed as Lilly’s) found a kilometer away in bushes, a sock in the woods, and unconfirmed reports of heat signatures detected by drone on disappearance day. By May 7, the RCMP scaled back operations, acknowledging the unlikelihood of survival in the rugged terrain and shifting to a criminal investigation. “We’re exploring all avenues,” Staff Sgt. Curtis MacKinnon stated at a press conference, emphasizing the involvement of major crime and forensic teams. Both parents voluntarily underwent polygraph tests on May 12, with results deeming their statements truthful on key redacted questions.

Yet, as weeks turned to months, frustrations mounted. Brooks-Murray, a member of the Sipekne’katik First Nation, relocated to stay with relatives elsewhere in the province, reportedly blocking Martell on social media amid escalating family tensions. Accusations flew from the mother’s side toward Martell, with some relatives openly questioning his involvement. Martell’s mother, Janie Mackenzie, who lived in a separate camper on the property, told investigators she heard the children laughing on backyard swings around 8:50 a.m. before dozing off again—a detail that has fueled timeline discrepancies.

Neighbors added to the intrigue, reporting hearing a vehicle idling and departing the property in the early hours of May 2—hours before the 911 call. One resident, identified only as “Smith” in court documents, speculated to police, “The car Smith heard was Daniel.” Martell denied any nighttime activity, insisting the family retired early: Brooks-Murray around 9 or 10 p.m., with him following suit. A review of local surveillance yielded no corroborating vehicle footage, but the RCMP seized phone records, banking data, and videos from both parents under the Missing Persons Act, citing the need to trace movements post-2:25 p.m. on May 1.

Court warrants also revealed police collecting personal items like the children’s toothbrushes for DNA analysis, alongside unrelated discoveries: a child’s T-shirt, blanket scrap, and tricycle during initial sweeps. Polygraphs cleared the parents on core queries, but redactions have sparked demands for a public inquiry from the children’s paternal grandmother, Belynda Gray. “We’ve spent hours in the woods,” Gray told The Globe and Mail, her voice cracking. “But without answers, it’s all for nothing.”

The biological father, Cody Sullivan—estranged for three years after a bitter custody battle—has stayed largely silent, living with Gray in Middle Musquodoboit. Police raided his residence and that of Martell’s uncle, Earle Martell, in the predawn hours of May 3, but found no links. Sullivan’s separation from Brooks-Murray, marked by her pursuit of full custody, left him out of the children’s lives, a point of raw pain for Gray. “Jack said he loved his grandpa the last time they spoke,” she recounted, clutching a fridge magnet plea for information.

Martell, meanwhile, has oscillated between hope and heartbreak. Four weeks in, he vented to CBC: “I can’t help but feel angry that there’s still no evidence.” He floated theories of abduction, noting the children’s undiagnosed autism spectrum traits made wandering unlikely—they rarely strayed far without coaxing. “They went for walks in the woods all the time, but we’d carry Jack when he tired,” Mackenzie added, doubting they could have ventured far alone. Yet, a woman’s unverified sighting of children matching their description on Gairloch Road around 9:30 a.m. May 2 has investigators circling back.

Enter the latest flashpoint: the November 15 volunteer search organized by Ontario-based Please Bring Me Home, a nonprofit specializing in cold cases. Up to 40 participants, including aunts, friends, and community members, gathered at Union Centre Community Hall, 15 kilometers from the site, to comb five kilometers of riverbank before winter snows bury potential evidence. Led by co-founder Nick Oldrieve, the group—initially hesitant to insert into an active probe—pivoted after pleas from Brooks-Murray’s relatives. “We focus on historical cases, but family convinced us,” Oldrieve said.

The day started promising: teams waded frigid waters, logged coordinates, and unearthed “items of interest”—a child’s T-shirt, blanket remnant, and tricycle fragment. But as one group neared a secluded bend, the atmosphere shifted. Relatives of Martell—identified in volunteer accounts as his brother and cousins—emerged from the treeline, faces flushed with fury. “This is family land! Get out!” one shouted, according to a searcher’s audio log obtained by CBC. Shoves followed, with a volunteer aunt, Cheryl Robinson (Brooks-Murray’s sister), alleging she was physically blocked from accessing a public access point. “They were screaming, getting in our faces,” Robinson told reporters post-search. “We weren’t hurting anyone—we were looking for my niece and nephew.”

The confrontation peaked when a Martell relative dialed 911, claiming “trespassers endangering the river.” RCMP arrived within 20 minutes, de-escalating but issuing no arrests. “The area is public, but tensions run high,” an officer noted in the call log. Volunteers, undeterred, pressed on, but the incident halted one team’s progress for hours.

Martell, reached by phone Friday, denied directing the interference. “My family’s hurting too—no one’s blocking justice,” he said, voice strained. “But outsiders trampling without coordination? It stirs up pain.” Mackenzie, the step-grandmother, echoed the sentiment: “We’ve been through hell. Let police handle it.” Yet, Brooks-Murray’s father, Henry Brooks, decried the blockade as “unforgivable.” “Those kids could be out there. Why fight the people trying to bring them home?” he told The Globe and Mail, his words heavy with the weight of Indigenous family ties strained by the probe.

RCMP spokesperson MacKinnon addressed the melee in a terse statement: “Items recovered were assessed and deemed not relevant to the investigation. We appreciate volunteer efforts but urge coordination to avoid conflicts.” The force has interviewed dozens, including the vehicle witnesses, and continues forensic analysis on seized items. “No stone unturned,” MacKinnon affirmed, though specifics remain sealed.

Public reaction has been visceral. Social media buzzes with #JusticeForLillyAndJack, amassing over 50,000 posts since the search. “Family blocking a search? That’s guilty as sin,” one X user fumed, echoing broader skepticism. Community vigils in Stellarton feature teddy bears and flowers at the RCMP detachment, a poignant reminder of the void left by two gap-toothed grins. Brooks-Murray, in a rare October plea, bared her soul: “The pure pain of not knowing has devastated us. I want my babies home.”

Experts caution against rushing to judgment. “Family conflicts in high-stress cases are common,” says Dr. Elena Vasquez, a forensic psychologist at Dalhousie University. “But blocking public land? That’s unusual—could stem from grief, fear of media sensationalism, or deeper issues.” She points to the autism factor: “These kids weren’t wanderers. If not accident, then foul play demands scrutiny.”

As winter looms, Please Bring Me Home vows to return. “We’re not stopping,” Oldrieve pledged. Gray, the paternal grandmother, calls for federal intervention: “A public inquiry—now. For Lilly, for Jack, for closure.”

In Lansdowne’s quiet woods, where blackflies once buzzed and children laughed on swings, silence reigns. The river rushes on, indifferent, as a fractured family grapples with shadows that refuse to fade. What truths lie buried along its banks? Only time—and unyielding pressure—may unearth them.

News

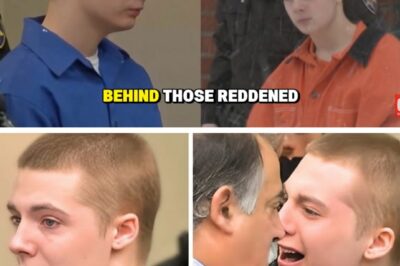

Schumaker initially claimed the toddler fell or injured himself accidentally but later admitted to losing control and striking him.

💥 FROM TEARS TO TERROR: 16-year-old Dylan Shoemaker sobbed in court, begging for mercy over the brutal d3ath of the…

In the execution chamber, Nichols made a final statement expressing sorrow

⚡ CHILLING END TO A 37-YEAR NIGHTMARE: Harold Wayne Nichols, the “Red-Headed Stranger,” has just been ex3cuted by lethal injection…

A second officer joined the effort but also fell through; both made it back to shore and were hospitalized for evaluation

❄️ “My husband! Please save him first!” — These desperate final words from a woman fighting for her life in…

Those simple, everyday words — now remembered as his last conversation with his mom — have brought fresh waves of grief to the family

🌟 A TRUE HERO AMONG US: 12-year-old Abel Mwansa didn’t run away from danger — he ran TOWARD it to…

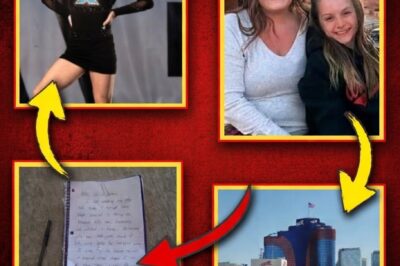

The investigation continues into the firearm, digital communications, and the note’s implications

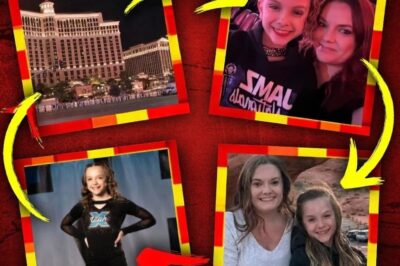

🚨 FIVE MISSED CALLS. A locked hotel room. And a horrifying 45-minute gap that sealed their fate… 11-year-old cheer star…

The competitive cheer world — with its demanding schedules, travel, and performance expectations — has been highlighted in discussions around the case

😱 CHILLING WITNESS ACCOUNT: “I heard them screaming at 7 AM.” — A hotel guest right next door at the…

End of content

No more pages to load