In the golden haze of a Santa Monica sunset, where the Pacific’s gentle waves lap against memories etched in sand, June Lockhart drew her final breath on October 23, 2025. At 100 years young, the actress whose warm smile and steadfast gaze defined motherhood for generations slipped away peacefully in her longtime home, surrounded by the quiet hum of family and the faint rustle of unread newspapers on her nightstand. It was 9:20 p.m., a time when most evenings might have found her savoring a cup of chamomile tea while flipping through the Los Angeles Times or the New York Times—her daily rituals of staying tethered to the world’s pulse, even as her own legacy spanned decades of flickering screens and heartfelt applause. Natural causes claimed her, a gentle fade after a life that roared with vitality, leaving behind a void as vast as the Hollywood soundstages she once commanded.

Lockhart’s passing, announced the following day by family spokesman Harlan Boll, sent ripples through the entertainment world—a poignant reminder of Hollywood’s Golden Age, where stars like her weren’t just performers but cultural anchors. She was the last of a vanishing breed: those who bridged vaudeville’s charm with television’s intimacy, infusing the small screen with a maternal grace that felt as real as a hug from across the living room. Tributes poured in swiftly, from co-stars who called her “the one-of-a-kind lady who did it her way” to fans who grew up whispering secrets to their own collies, inspired by her unflappable poise. Bill Mumy, the boyish Will Robinson from Lost in Space, posted a heartfelt farewell on social media, his words a balm: “A talented, nurturing, adventurous, and non-compromising soul. June will always be one of my very favorite moms.” In an era of reboots and remakes, her death feels like the closing chapter on an original script—one written in earnest dialogue and unyielding optimism.

Born June Kathleen Lockhart on June 25, 1925, in the bustling heart of New York City, she entered the world as an only child to a pair of luminous performers whose own legacies would cast long shadows. Her father, Gene Lockhart, was a prolific character actor whose gravelly voice and twinkling eyes made him a staple in over 200 films, from the villainous Regina Giddens’ scheming uncle in The Little Foxes to the jolly Judge Santa Claus in Santa Claus Conquers the Martians. Her mother, Kathleen Lockhart, brought ethereal grace to the stage and screen, her roles often laced with quiet strength—much like the daughter who would inherit her poise. The Lockharts’ romance itself was the stuff of showbiz lore: hired separately for a touring production backed by Thomas Edison in the early 1900s, they met amid the Rocky Mountains’ splendor during a stop at Lake Louise, Alberta. There, under a canopy of evergreens and glacial blues, they vowed eternal partnership, a union that birthed not just a family but a dynasty of dramatic flair.

June’s earliest memories were steeped in greasepaint and spotlights, the scent of stage fog mingling with her mother’s perfume. By age eight, she was no longer a spectator; she danced in the children’s ballet troupe for a Metropolitan Opera House production of Peter Ibbetson in 1933, her tiny feet twirling through dreamlike sequences that foreshadowed a lifetime of graceful navigation. The family relocated to Hollywood a decade later, chasing the silver screen’s siren call. Gene’s steady work as a character player—often the kindly uncle or the scheming banker—provided stability, while Kathleen’s supporting turns in films like All This, and Heaven Too added sparkle. Young June, wide-eyed and watchful, absorbed it all: the elation of a well-received line, the sting of a director’s cut, the camaraderie of craft services shared under studio lots’ relentless sun.

Her film debut arrived at 13, a poignant family affair in 1938’s adaptation of A Christmas Carol. As Belinda Cratchit, the eldest daughter in the impoverished yet resilient Bob Cratchit household, June stood opposite her parents—Gene as the ghost of Jacob Marley, Kathleen as the spectral Mrs. Cratchit— in a tableau of Victorian warmth amid Dickensian chill. The role, small but shimmering, captured her innate tenderness: a girl’s hopeful gaze piercing the gloom, much like the collie who would later become her on-screen companion. Hollywood beckoned with ingenue parts thereafter. In 1940’s All This, and Heaven Too, she played a schoolgirl alongside Bette Davis, her fresh-faced innocence a counterpoint to the melodrama’s swirling passions. Adam Had Four Sons (1941) cast her as vulnerable Fanny, her performance earning whispers of promise from critics who noted her “poised vulnerability.” By 1941, at the height of World War II’s shadow, she embodied young love in Sergeant York, sharing tender moments with Gary Cooper’s titular hero, her character’s quiet fortitude mirroring the era’s unspoken rallying cry.

But it was the stage that truly ignited her star. At 18, Lockhart conquered Broadway in a revival of For Love or Money, her portrayal of a plucky socialite earning a Tony Award in 1947—a feather in her cap that showcased her comic timing and emotional depth. “She had that rare gift,” a theater critic recalled decades later, “of making audiences laugh until their sides ached, then holding them in hushed silence with a single, soulful glance.” Off-Broadway stints and summer stock followed, honing her craft amid the post-war boom. Yet, as radio faded and television flickered to life, Lockhart sensed the tide turning. “The future’s in the box,” she quipped to her agent in 1950, her intuition as sharp as her wit. Little did she know that the “box” would crown her as America’s quintessential TV mom, a role that would endure far beyond the final fade to black.

Television’s embrace was swift and defining. In 1958, CBS tapped her for Lassie, the long-running saga of a loyal collie and the family she cherished. As Ruth Martin, the devoted farm wife to Paul Martin’s (played by Hugh Reilly) steadfast husband and mother to the orphaned Timmy (Jon Provost), Lockhart embodied rural resilience. The Martins’ Miller’s Grove homestead, a verdant idyll of apple orchards and white picket fences, became a weekly refuge for 11 million viewers. Ruth was no damsel; she mended fences, baked pies, and dispensed wisdom with a calm authority that masked the era’s undercurrents of gender roles. When Timmy tumbled into wells or Lassie trekked through blizzards, it was Ruth’s steady hand—voicing concern without hysteria—that grounded the drama. “What harm?” she’d murmur, echoing the show’s tagline, her voice a soothing balm for Cold War anxieties.

The role, from 1958 to 1964, earned her two Emmy nominations, including one for outstanding lead actress in a drama series—a testament to her ability to elevate a children’s show into family gospel. Off-set, Lockhart infused authenticity: baking real apple pies for cast potlucks, teaching Provost knot-tying on location in Chatsworth’s rolling hills. “June was the real deal,” Provost reflected in a 2023 memoir. “She mothered us all—Lassie included.” The collie, a series of nine generations over two decades, adored her; handlers joked that the dog’s tail-wags doubled on her close-ups. Lassie‘s cultural footprint was immense—teaching empathy, environmentalism, and the power of unspoken bonds—but Lockhart’s Ruth made it human, a matriarch whose quiet strength whispered that home, no matter how humble, was the ultimate adventure.

Yet Lockhart craved variety, and 1965 delivered it in cosmic proportions. Irwin Allen’s Lost in Space, CBS’s bold foray into space opera, cast her as Maureen Robinson, the biochemist matriarch of a family exiled aboard the Jupiter 2. Stranded light-years from Earth after a sabotage-fueled launch glitch, the Robinsons—Maureen, husband John (Guy Williams), and children Judy (Marta Kristen), Penny (Angela Cartwright), and Will (Bill Mumy)—navigated alien worlds with a mix of peril and pluck. Maureen was no aproned hausfrau; she wielded test tubes in zero gravity, decoded extraterrestrial flora, and faced cyclopean monsters with a scientist’s curiosity. “Danger, Will Robinson!” became the catchphrase, but it was Maureen’s “We must keep exploring” that fueled the family’s forward march.

Filmed in Irwin Allen’s spectacle-driven style—exploding sets, rubbery creatures, and Irwin Allen’s spectacle-driven style—Lost in Space ran for three seasons, blending campy thrills with heartfelt family dynamics. Lockhart’s Maureen balanced the show’s excesses: soothing Penny’s fears amid glowing amoebas, debating ethics with the scheming Dr. Zachary Smith (Jonathan Harris), and sharing stargazing moments with John that evoked Lassie‘s intimacy against a galactic canvas. “June brought gravity to the weightless,” Mumy later said, pun intended. The series flopped initially, squeezed between Bonanza and The Red Skelton Show, but cult status bloomed in syndication. By the 1980s, conventions buzzed with fans in silver jumpsuits, and Lockhart, ever gracious, signed autographs with quips about “surviving more asteroids than most marriages.”

Her television tenure didn’t end in orbit. From 1968 to 1970, she brought wry competence to Petticoat Junction as Dr. Janet Craig, the bespectacled veterinarian who charmed the Shady Rest Hotel’s quirky clan. Guest spots followed like constellations: a no-nonsense judge on Perry Mason, a ghostly aunt in The Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew Mysteries, and recurring arcs on soaps like General Hospital and One Life to Live. In the 1990s, she popped up in Beverly Hills, 90210 as a wise mentor, and even lent her voice to animated fare like The Tick. At 80, she guest-starred on Roseanne and 7th Heaven, her timing as sharp as ever. “Age is just a number,” she’d say with a wink, “and mine’s unlisted.”

Away from the cameras, Lockhart’s life mirrored her on-screen serenity, though not without its tempests. In 1951, she wed Dr. John F. Maloney, a dashing Navy physician whose steadiness complemented her whirlwind career. Their union bore two daughters: Anne Lockhart, who carved her own path in acting with roles in Battlestar Galactica and The Fog, and June Elizabeth Trola, a producer who kept the family flame alight. Divorce came in 1959, a quiet unraveling amid Hollywood’s glare, followed by a brief 1966 marriage to architect John Lindsay. Lockhart poured her energies into single motherhood, shuttling between sets and school plays, her home a haven of homemade lasagnas and bedtime stories from The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Philanthropy beckoned too: a board member for the Actors Fund, she championed hearing dog programs—fitting for an era when her own hearing waned but her advocacy sharpened—and supported journalistic watchdogs like ProPublica, ever the news devourer.

As the 21st century dawned, Lockhart became a living bridge to Hollywood’s past. At 90, she attended Lost in Space‘s Netflix reboot premiere in 2018, beaming alongside the new Robinsons, her presence a blessing. NASA visits thrilled her; young astronauts, inspired by Maureen’s intellect, sought her counsel on perseverance. “She was delighted,” daughter June Elizabeth shared, “that her fictional mom sparked real stars.” Honors accrued: two Hollywood Walk of Fame stars—one for film, one for TV—and a lifetime achievement nod from the Saturn Awards. Yet Lockhart shunned fuss, preferring crossword puzzles to red carpets, her Santa Monica bungalow a time capsule of scripts and collie photos.

June Lockhart’s death at 100 closes a century of light— from Dickensian hearths to distant nebulae, she mothered us all. In an age of fractured families and fleeting feeds, her Ruth and Maureen endure as beacons: women who mended worlds with wisdom, who faced blizzards and black holes with unyielding grace. As the credits roll on her extraordinary run, we whisper, “What harm?”—and find solace in the answer: none. She leaves a legacy as vast as space itself, her warmth eternal, her smile the stuff of dreams that never fade.

News

“My Son’s Blood Is on Their Hands”: Distraught Mother Blames Crans-Montana Authorities After 17-Year-Old Son Vanished in New Year’s Bar Fire

The devastating fire that tore through Le Constellation bar in the upscale Swiss ski resort of Crans-Montana on New Year’s…

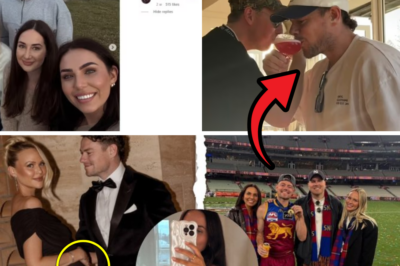

Evidence from Instagram — Lachie Neale and Tess Crosley’s Relationship Began When Jules Was Pregnant, Netizens Claim

The scandal surrounding Brisbane Lions star Lachie Neale has deepened with online sleuths uncovering what they claim is compelling evidence…

“I Will Not Let What Happened Between Me and My Husband Affect the Children” — Jules Neale Shares Her Future Plans for Piper and Freddie

Jules Neale has shared her upcoming plans for her children amid the ongoing fallout from her separation from Brisbane Lions…

“Tess Knew All Our Secrets — And Seemed So Excited to Hear About My Family” — Jules Neale Breaks Silence on Tess Crosley’s Close Ties to the Neale Family

The scandal engulfing Brisbane Lions co-captain Lachie Neale has taken another emotional turn as his estranged wife, Jules Neale, has…

Tess Crosley May Have Revealed a Cryptic Clue About Her Marriage Status Amid the Scandal Rocking AFL Star Lachie Neale’s Shock Split from Wife Jules

The off-season drama surrounding Brisbane Lions superstar Lachie Neale has escalated into one of the most talked-about scandals in Australian…

Tragic Discovery in Lake Michigan: Police Recover Linda Brown’s Body and a Suspicious Item — Her Husband Collapses Upon Seeing It

The search for missing Chicago Public Schools teacher Linda Brown ended in heartbreak on January 12, 2026, when her body…

End of content

No more pages to load