In the opulent corridors of Buckingham Palace, where crystal chandeliers cast a perpetual glow over gilded banqueting halls and the air hums with the faint clink of silverware on porcelain, meals have always been more than sustenance—they are theater, tradition, and a subtle barometer of power. For decades, the royal kitchens buzzed with the quiet urgency of fulfilling whims that could range from the Queen’s simple grilled fish to elaborate state banquets fit for emperors. But few tales from those hallowed hearths reveal the stark contrasts in royal palates quite like the recent disclosures from Dan Ottaway, a former Buckingham Palace chef whose tenure spanned the late Queen’s reign. Speaking candidly to the Irish Independent, Ottaway has peeled back the layers on Prince Andrew’s notoriously demanding dining habits, painting a portrait of a prince whose eleventh-hour extravagances tested the limits of even the most seasoned culinary staff. As Andrew navigates his diminished status amid financial scrutiny and family pressures, these revelations serve as a poignant reminder of a bygone era of unchecked indulgence, one that once defined his life at the heart of the monarchy.

Ottaway, a Wicklow-based culinary veteran who traded the Palace’s rigid protocols for the emerald serenity of Ireland’s coast, served in the royal kitchens during a pivotal time—the 1990s and early 2000s—when the House of Windsor grappled with divorces, scandals, and the inexorable march toward modernity. His reflections, delivered with the wry detachment of someone who has plated pheasant for presidents and poached eggs for princes, zero in on Andrew as the outlier among his siblings. “Prince Andrew was quite difficult,” Ottaway recalled, his tone laced with the exhaustion of recalled chaos. “Much more demanding than the others.” While royals like Charles (then Prince of Wales) and Anne submitted detailed menus weeks in advance—meticulous spreadsheets outlining dietary preferences, portion sizes, and even the arrangement of garnishes—Andrew operated on a whim, flooding the kitchens with elaborate last-minute requests that upended the day’s rhythm. A casual lunch for a handful of guests could balloon into a feast requiring fresh lobster airlifted from Cornwall or truffles shaved tableside, all demanded with the nonchalance of someone accustomed to the world bending to his fork.

These impulses weren’t mere caprice; they stemmed, in Ottaway’s view, from Andrew’s cherished position as the Queen’s favorite son. Born second to Charles in 1960, Andrew—christened the “routinely charming” spare by palace insiders—enjoyed a gilded youth unmarred by the heir’s burdens. His naval service in the Falklands War elevated him to national hero status, and post-marriage to Sarah Ferguson in 1986, he reveled in the trappings of a playboy prince. Palace staff whispered that this favoritism granted him a velvet rope around protocol: no advance notice required, no budgets strictly enforced. “Nobody would tell him off,” Ottaway noted, a sentiment echoed by countless ex-employees who navigated Andrew’s orbit with a mix of deference and dread. One particularly vivid anecdote from Ottaway’s tenure involved a spontaneous polo afterparty in the mid-1990s. With mere hours’ notice, Andrew insisted on a buffet for 20 riders—rare Wagyu steaks grilled to bloody perfection, caviar blinis stacked like silver dollars, and vintage Dom Pérignon chilled to 42 degrees Fahrenheit. The kitchens, already prepping for a state dinner, scrambled like commandos, repurposing silver salvers and commandeering the butler’s pantry. “It was chaos,” Ottaway admitted, “but that’s what made it Andrew.”

This penchant for the impromptu extended beyond solo suppers to grand gestures that blurred the line between hospitality and hubris. During his tenure as the UK’s trade envoy in the 2000s—a role that took him jet-setting to Silicon Valley salons and Gulf state galas—Andrew’s Palace soirees became legendary for their excess. Chefs recall frantic calls at dusk for “something special” to impress Kazakh oligarchs or American tech moguls: think osso buco simmered for eight hours in Barolo, paired with a 1982 Château Margaux decanted precisely at serving time. Ottaway highlighted how these demands cascaded down the chain, pressuring junior sous-chefs to improvise without waste— a tall order when Andrew’s appetite, ironically, was as fickle as his moods. “He ate like a bird,” the chef observed, contrasting the prince’s nibbling with the hearty portions he’d order. Starters might vanish untouched while mains cooled on ornate Wedgwood platters, a testament to the performative nature of his entertaining. Yet, no plate went uneaten for long; palace protocol dictated that “tastings” be dispatched to staff quarters, turning royal rejects into midnight feasts for the below-stairs brigade.

Andrew’s ex-wife, Sarah Ferguson—the vivacious Duchess of York whose red hair and ready laugh once symbolized the monarchy’s attempt at relatability—emerges as a co-conspirator in this culinary caper. Their 1986 wedding, a spectacle of tartan sashes and fairy-tale frocks, masked a union that would soon strain under the weight of extravagance. As detailed in Andrew Lownie’s 2023 exposé The Crown in Crisis (often misremembered as Entitled in tabloid retellings), a dismissed palace courtier spilled the beans on Fergie’s nightly indulgences, which made Andrew’s quirks seem tame by comparison. “Every night she demands a whole side of beef, a leg of lamb, and a chicken,” the insider alleged, describing a ritual where these hauls were laid out on the dining room sideboard like a medieval hunt’s bounty. For Fergie and her daughters, Beatrice and Eugenie—then wide-eyed girls enchanted by the Palace’s grandeur—the spread was a nightly Narnia. But reality bit hard: much of the bounty rotted untouched, carved sporadically before being discreetly discarded to avoid scandal. “It was Henry VIII-level excess for three people,” the courtier quipped, estimating the waste at thousands of pounds weekly in today’s currency.

This profligacy, Lownie argues, wasn’t isolated folly but a symptom of the Yorks’ gilded isolation. Post-1996 divorce, Fergie—stripped of her HRH but not her tastes—continued mooching off the Palace’s largesse, her demands a lifeline amid mounting debts from bad investments and tabloid-fueled spending sprees. The side-of-beef saga, corroborated by multiple staffers in Lownie’s interviews, underscores a deeper dysfunction: Andrew and Fergie’s shared love of the lavish masked deeper insecurities. He, the Falklands hero turned Epstein associate, sought validation through virtuoso hosting; she, the “Fergie who would be queen,” through feasts that echoed her pre-royal equestrian feasts. Palace economists, quietly tallying the toll, linked these habits to the couple’s chronic cash crunches—Fergie’s 2010 toe-sucking scandal barely registering against her £4 million in bailouts from Andrew, funded in turn by shadowy donors. “The table was their downfall,” one anonymous footman reflected in Lownie’s tome, a line that captures the tragicomic irony of royals felled not by swords, but by surpluses of sirloin.

In stark relief stand the more measured appetites of Andrew’s relatives, as Ottaway’s anecdotes illuminate the monarchy’s evolving palate. The late Queen Elizabeth II, whom Ottaway served with reverent awe, epitomized restraint. “She ate to survive,” he said plainly, describing her routine as a model of monastic minimalism: poached eggs on toast for breakfast, Dover sole with steamed greens for lunch, and a modest dinner of roast chicken or game pie, portioned to the gram. No seconds, no fuss—dessert a rare compote of fruit from the Sandringham orchards, savored in solitude with a single gin and Dubonnet. This frugality, born of wartime rationing and unyielding duty, extended to her family: Charles favored foraged mushrooms and organic heirlooms from Highgrove, while Anne demanded her salmon grilled “just so,” with a side of tartare sauce measured in teaspoons. Even the youthful exuberance of William and Kate brought gratitude, not entitlement. Ottaway beamed recounting how the then-Duchess of Cambridge would parade her children through the kitchens post-meal, little George and Charlotte piping “thank you” choruses that melted the hardened hearts of line cooks. “Kate made it personal,” he said. “She understood the human side of the service.”

These contrasts paint Andrew not as an anomaly, but as the last echo of a vanishing royal archetype—the entitled second son, shielded by maternal indulgence until the world intruded. His scandals, from the 2019 Newsnight interview to the Epstein fallout, have stripped away the silverware’s shine, forcing a reckoning with austerity. Today, at 65, Andrew clings to Royal Lodge, the sprawling Windsor pile he shares with Fergie in a post-divorce détente of convenience. King Charles, ever the eco-austere heir, has slashed his brother’s £250,000 annual allowance, prompting whispers of eviction to the smaller Frogmore Cottage—once Harry and Meghan’s exile. Palace menus have slimmed accordingly: no more eleventh-hour extravaganzas, just sensible suppers of seasonal veg and lean proteins, aligned with Charles’s “farm-to-fork” ethos. Fergie, battling her own health woes (a 2024 skin cancer diagnosis following breast cancer), has pivoted to frugality, hawking her A Most Intriguing Lady novels and Weight Watchers ambassadorships to offset the ghosts of gluttony.

Yet, as Ottaway’s tales remind us, the royal table has always mirrored the throne’s tempests. In an age of Netflix exposés and Instagram feasts, Andrew’s demands—once the stuff of below-stairs gossip—now symbolize a monarchy at the crossroads: shedding excess to survive scrutiny. For the chefs who toiled in its shadow, like Ottaway now crafting Wicklow seafood specials in his coastal haven, the memories linger like a well-seasoned sauce—bitter, bold, and utterly unforgettable. As Andrew faces potential downsizing, one wonders if his palate, too, will adapt: from sides of beef to simple slices of humble pie. In the end, the most demanding diner may not be the prince at the head of the table, but time itself, portioning out legacies with impartial precision.

News

“My Son’s Blood Is on Their Hands”: Distraught Mother Blames Crans-Montana Authorities After 17-Year-Old Son Vanished in New Year’s Bar Fire

The devastating fire that tore through Le Constellation bar in the upscale Swiss ski resort of Crans-Montana on New Year’s…

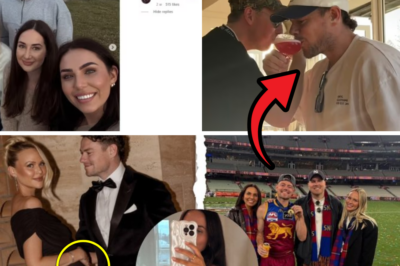

Evidence from Instagram — Lachie Neale and Tess Crosley’s Relationship Began When Jules Was Pregnant, Netizens Claim

The scandal surrounding Brisbane Lions star Lachie Neale has deepened with online sleuths uncovering what they claim is compelling evidence…

“I Will Not Let What Happened Between Me and My Husband Affect the Children” — Jules Neale Shares Her Future Plans for Piper and Freddie

Jules Neale has shared her upcoming plans for her children amid the ongoing fallout from her separation from Brisbane Lions…

“Tess Knew All Our Secrets — And Seemed So Excited to Hear About My Family” — Jules Neale Breaks Silence on Tess Crosley’s Close Ties to the Neale Family

The scandal engulfing Brisbane Lions co-captain Lachie Neale has taken another emotional turn as his estranged wife, Jules Neale, has…

Tess Crosley May Have Revealed a Cryptic Clue About Her Marriage Status Amid the Scandal Rocking AFL Star Lachie Neale’s Shock Split from Wife Jules

The off-season drama surrounding Brisbane Lions superstar Lachie Neale has escalated into one of the most talked-about scandals in Australian…

Tragic Discovery in Lake Michigan: Police Recover Linda Brown’s Body and a Suspicious Item — Her Husband Collapses Upon Seeing It

The search for missing Chicago Public Schools teacher Linda Brown ended in heartbreak on January 12, 2026, when her body…

End of content

No more pages to load