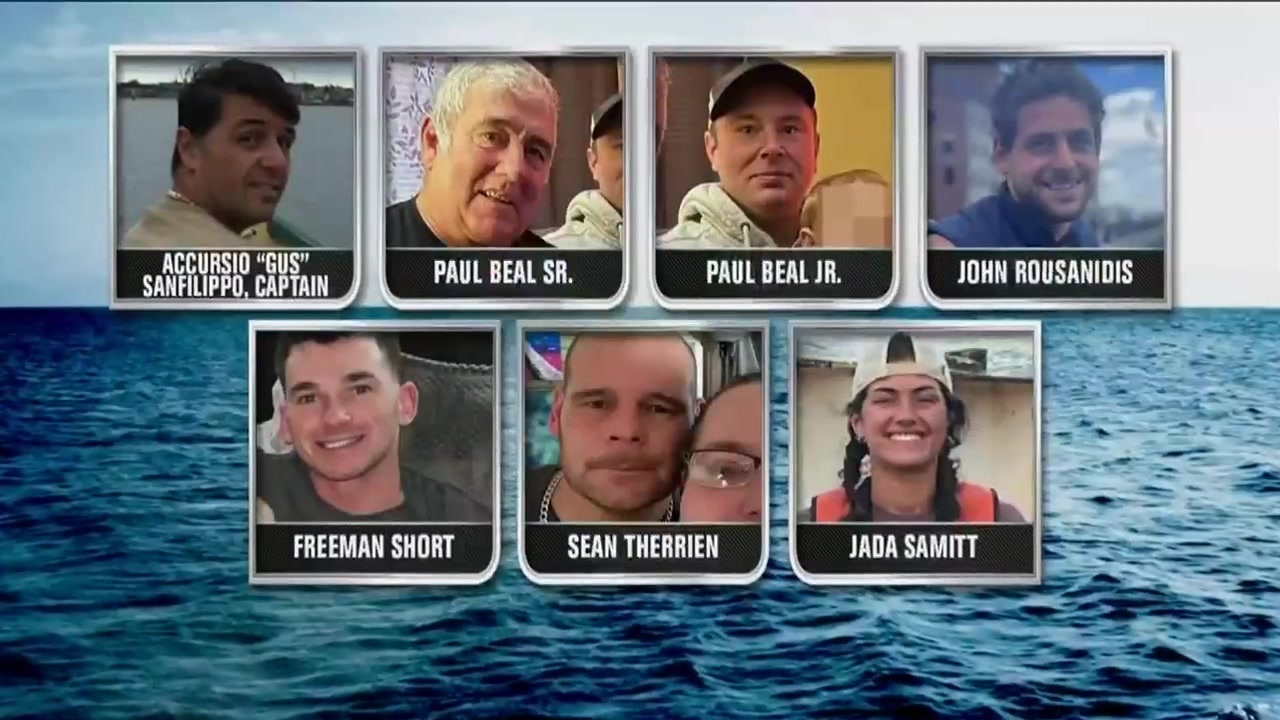

In the unforgiving freeze of Gloucester’s winter waters, where the Atlantic claims lives without mercy, the sinking of the fishing vessel Lily Jean has ripped open fresh wounds in America’s oldest seaport. Among the seven souls swallowed by the sea were Paul Beal Sr. and his son Paul Beal Jr.—a father-son duo whose unbreakable bond on the water ended in tragedy, leaving their family shattered yet clinging to one devastating sliver of solace amid the grief.

Lauren Beal, wife to Paul Sr. and mother to Paul Jr., stood outside St. Ann’s Church during a tear-soaked vigil, her voice trembling as she spoke of the unimaginable loss. “They are going to be deeply missed,” she said, the words heavy with sorrow. “It’s such a tragedy that this happened. But at least they were together when the boat went down. That’s all I can say.”

That raw, bittersweet admission has echoed through Gloucester like a tolling bell, capturing the profound pain and faint comfort in a community where fishing isn’t just a livelihood—it’s a family legacy, passed down through blood and salt. The Beals were part of that enduring tradition: Paul Sr., a veteran deckhand with decades on the Georges Bank, and Paul Jr. (often called PJ), following in his father’s footsteps as a dedicated crew member. Together they hauled scallops and groundfish, shared the grueling watches, and returned to harbor with stories and catches that sustained not just their household but the tight-knit fabric of Gloucester life.

The Lily Jean, a rugged 72-foot workhorse once spotlighted on the History Channel’s “Nor’Easter Men,” set out that fateful January 30, 2026, under Captain Accursio “Gus” Sanfilippo’s steady command. Conditions were brutal—air temperatures plunging to 12°F, wind chills biting harder, and freezing spray turning every surface into a hazard—but for these men, it was business as usual. No major storm warnings blared; the seas were manageable at 4 feet with gusts around 27 mph. Veterans like the Beals trusted their experience, their skipper’s judgment, and the boat’s proven track record. They slipped the lines and headed offshore, chasing the catch as generations had before them.

Then, silence. At 6:50 a.m., the vessel’s emergency position-indicating radio beacon (EPIRB) fired off an automated distress signal—no voice crackling over the radio, no mayday plea, just a desperate electronic scream from 25 miles off Cape Ann. Coast Guard helicopters and cutters raced through the dawn chill, arriving to a scene of pure devastation: floating debris scattered across the swells, an empty life raft drifting aimlessly, and one unresponsive body in the frigid 39°F water. That body was later confirmed as Captain Sanfilippo, the fifth-generation fisherman whose infectious smile had welcomed so many home.

A massive search ensued, scouring over 1,000 square miles with aircraft, cutters, and small boats battling ice and exhaustion. But the ocean yielded nothing more. The remaining six crew—Paul Beal Sr., Paul Beal Jr., John Rousanidis (33), Freeman Short (31), Sean Therrien (44), and NOAA fisheries observer Jada Samitt (22)—were presumed lost when the effort was suspended on January 31 as another nor’easter threatened. The Coast Guard’s Northeast District, with potential NTSB support, has launched a formal probe into the cause: perhaps a sudden hull breach from ice accumulation, a catastrophic gear failure, or some unseen peril in depths of 350-400 feet where the wreck may lie forever out of reach.

The double loss of father and son has amplified the heartbreak exponentially. Paul Sr. was a fixture in the harbor, known for his reliability and quiet strength; Paul Jr. brought youthful energy to the deck, learning the ropes from the man who raised him. Family members, including uncle Ricky Beal, described the blow as “just devastating—I can’t explain it.” A GoFundMe for the Beal family quickly surpassed $19,000 of its $30,000 goal, with nephew Dean DeCoste writing that the men were “gone too soon… a husband, grandfather, father, son, brother, uncle, cousin, and great friends to many in the community.”

Their story is one thread in a tapestry of grief enveloping Gloucester. John Rousanidis brought kindness from the Salem area; Freeman Short’s sister Grace Bernaiche remembered his “strong man” physique matched by a “loving and gentle” heart; Sean Therrien offered humor and help whenever needed. Jada Samitt, the 22-year-old Virginia native and University of Vermont graduate, shone with compassion and bravery—her family mourning a vibrant spirit who believed deeply in ocean protection and pulled double duty as observer and crew.

Vigils at St. Ann’s drew crowds of weathered fishermen, families, and neighbors sharing tears and candles. Flowers and cards pile at the iconic Fisherman’s Memorial, where Gloucester’s mayor Paul Lundberg vowed the Lily Jean names would join thousands etched in stone. Donations pour into Fishing Partnership Support Services marked “Lily Jean,” while NOAA paused observer deployments amid the sorrow and incoming weather.

This tragedy echoes past horrors—the Andrea Gail, endless empty berths—but strikes harder in its suddenness and proximity. No raging Perfect Storm, just routine winter fishing turning lethal in an instant. Yet Gloucester’s spirit endures. The fleet will head out again because the sea provides, because tradition demands it, because men like the Beals lived for it.

For Lauren Beal and her family, the pain is raw and unending. But in the darkest hour, that one fragile comfort persists: father and son, together to the end, bound by love, work, and the unforgiving ocean that finally claimed them both. Seven lives extinguished, a community forever changed, but the harbor’s heartbeat—fierce, resilient—beats on.

News

“NOT EVERYONE AGREED WITH THIS PLAN”: Police Reveal Second Handwritten Letter in Mosman Park Horror—Jarrod Clune’s Handwriting Confirms He Alone May Have Orchestrated the Murder-Suicide, Wife and Sons Unaware of Deadly Pact

In the sun-drenched streets of Mosman Park—one of Perth’s most exclusive enclaves, where ocean breezes mask hidden desperation—a family’s final…

HEARTBREAKING NEWS: One Month After Swiss Bar Inferno, 29-Year-Old Eleonora Palmieri Remains Hospitalized with Disfigured Face—Survivor Breaks Silence on Horrific Stampede Where Panicked Revelers Pushed Toward Locked Door in Deadly Chaos

One month after flames devoured the Le Constellation bar in the glamorous Swiss ski resort of Crans-Montana, turning a jubilant…

“WE NEVER THOUGHT IT WOULD END LIKE THIS…”: Police Uncover Second Handwritten Letter in Mosman Park Horror—Parents’ Secret Pact Revealed Behind Closed Doors in Devastating Double Murder-Suicide

In the affluent quiet of Mosman Park—one of Perth’s most exclusive suburbs, where manicured lawns and ocean views hide everyday…

“OUR HEARTS ARE BROKEN”: Parents of 15-Year-Old Sharon Maccanico Confirm Devastating Loss in Mount Maunganui Landslide—Inseparable Teens Sharon and Boyfriend Max Furse-Kee Taken Together in Seconds, One Heart-Wrenching Detail from Tribute Leaves Community in Tears

In a nightmare that no parent should ever endure, the parents of 15-year-old Sharon Maccanico have spoken out in raw…

“The Gentlemen Choose to Stay”: Heroic Act of Chivalry Revealed in Lily Jean Tragedy—Crew Gave Sole Life Vest to Young Observer Jada Samitt, Dooming Themselves as She Was Found Dead from Hypothermia Clinging to It

In the merciless freeze of the North Atlantic, where water temperatures hovered at a lethal 39°F and air plunged to…

“If I Don’t Come Back, Tell Them I’m Sorry”: Heartbreaking Final Note from Captain Gus Sanfilippo Found in His Pocket by Devastated Wife and Children—Last Words Before Lily Jean Vanished into Icy Atlantic with Entire Crew

In the salt-crusted home of Gloucester’s most beloved skipper, where fishing gear still hangs in the hallway and the smell…

End of content

No more pages to load