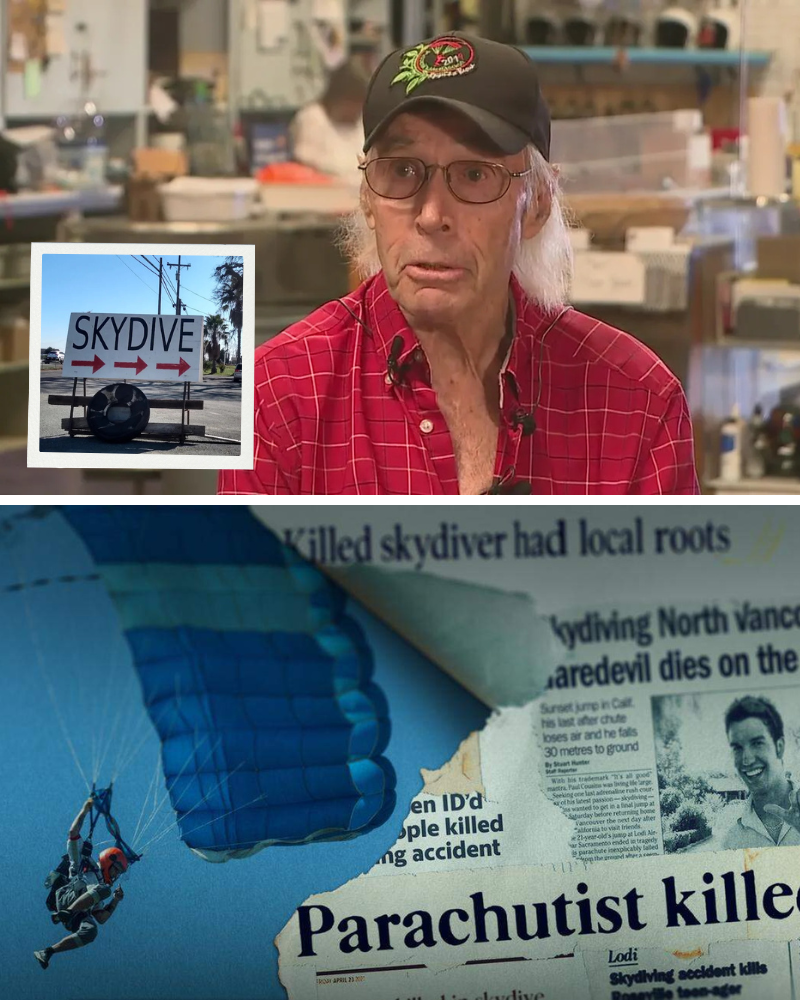

William “Bill” Dause, the 81-year-old owner of the Lodi Parachute Center in California, has consistently maintained that skydiving is an inherently risky sport and that the facility’s 28 fatalities since 1985 are unrelated incidents, not evidence of systemic failure, famously likening them to traffic accidents that do not result in road closures.

Dause, who purchased the land at Lodi Airport in Acampo in 1981 and has operated the drop zone under various names including Skydive Lodi and Acme Aviation, has built a reputation for a no-frills, high-volume operation catering primarily to experienced jumpers. With over six decades in the industry—starting as a rigger in the 1960s—he estimates thousands of annual jumps without maintaining formal logs, a practice he defends as standard for smaller facilities.

In multiple interviews following high-profile incidents, Dause has articulated a philosophy rooted in personal responsibility and the sport’s inherent dangers. His most quoted analogy came in a 2016 conversation with The Sacramento Bee after the tandem jump tragedy involving 18-year-old Tyler Turner: “When there’s an accident on the freeway, you don’t see them close the freeway,” he said, emphasizing that isolated events should not halt operations. He reiterated this stance in 2021 following the death of Sabrina Call, telling reporters, “People die. It’s part of life. You can’t stop everything because someone gets hurt.”

Dause argues that each incident—from parachute entanglements to wind drifts—stems from individual errors or environmental factors, not operational flaws. “We’ve had people from all over the world jump here safely,” he stated in a 2023 phone interview with SFGATE. “The ones who don’t make it? They made a mistake, or the wind changed, or equipment failed in a way no one could predict. That’s skydiving.” He points to the center’s longevity and lack of insurance claims paid out as proof of prudent management, despite a $40 million judgment against him in the Turner case, which remains uncollected.

This perspective aligns with his decision to operate outside the United States Parachute Association (USPA). Dause has never enrolled the center in the organization, citing cost—up to $750 annually—and philosophical differences. “The USPA wants control, but I’ve been doing this longer than most of them have been alive,” he told The Modesto Bee in 2019. “Their rules are for big commercial places. We’re a club for real jumpers.” He maintains that his staff, though not USPA-certified, are experienced, with some holding thousands of jumps.

Supporters within the skydiving community echo elements of Dause’s view. Veteran jumper Cory Christiansen, a retired Army parachutist, told Parachutist magazine in 2022 that “risk is baked into the sport—zero defects isn’t realistic.” He noted that Lodi attracts advanced practitioners attempting complex formations, which carry higher statistical danger than tandem novice jumps at USPA-affiliated sites. Online forums like Dropzone.com feature defenders who praise the center’s “old-school” vibe and low prices, with one user writing in 2024, “Bill keeps the spirit of skydiving alive. Not everything needs a corporate handbook.”

Critics, however, challenge the freeway analogy as dismissive. Francine Turner, whose son died in 2016, responded in a 2023 interview: “Highways have traffic engineers, speed limits, inspections. Skydiving at Lodi has… Bill’s opinion.” She and other families argue that without jump logs, incident reviews, or third-party audits, patterns go unaddressed. The USPA’s Ron Bell counters that while no system eliminates risk, data-driven protocols—like mandatory reserve repacks every 180 days—reduce it significantly, citing a national fatality rate drop from 1 in 56,000 jumps in the 1980s to 1 in 253,000 today.

Dause’s stance has legal ramifications. In the 2021 civil ruling holding him personally liable for Turner’s death, Judge Lesley Holland noted his “cavalier attitude” toward safety documentation, including missing training records for instructor Yong Kwon. The October 2024 conviction of instructor Robert Pooley for forging certifications—training conducted at Lodi—further undermined claims of rigorous oversight.

Regulatory bodies remain limited in reach. The FAA fined the center nearly $1 million in 2010–2011 for aircraft maintenance violations but collected nothing, and skydiving operations fall outside direct federal jurisdiction beyond pilot and rigger certifications. San Joaquin County has no specific ordinances, and “Tyler’s Law” (2017) only mandates credential verification, not affiliation.

As of October 2025, Dause continues daily operations, answering phones and scheduling loads. The center ceased tandem jumps per FAA guidance post-2019 but hosts solo and formation skydiving. No fatalities have been reported since 2021, which Dause cites as vindication: “See? We learn, we adjust, we keep jumping.”

His philosophy resonates with a segment of the community that views skydiving as a personal pact with gravity. Yet for families and safety advocates, it reads as resignation. The National Transportation Safety Board’s 2023 call for centralized jump data—currently voluntary via USPA—could shift the debate, but implementation lags.

Dause, now in his ninth decade, shows no signs of retiring. “I’ll be here till they carry me out,” he told a local reporter in 2024, standing beside a Cessna as another load boarded. For him, the sky remains open—risks and all. Whether that openness invites progress or peril remains the question families like the Turners refuse to let fade.

News

Rihanna Responds to a Fan Saying, “They Saying It’s 2016, Rih”: What Her Viral Reply Really Means

When a fan recently commented, “They saying it’s 2016, Rih,” few expected Rihanna to respond. She often ignores random online…

Rihanna’s Unmatched Face Card: How One Look Became a Cultural Phenomenon

Few celebrities command attention the way Rihanna does. Across red carpets, candid street photographs, and unfiltered social media moments, one…

400,000 FRANCS FOR RELEASE: PROSECUTORS SEEK BAIL FOR OWNERS AFTER DEADLY CRANS-MONTANA NEW YEAR FIRE

Prosecutors in Sion have requested a total of 400,000 Swiss francs in bail to grant provisional freedom to Jacques and…

📰 RCMP RELEASES NEW TIMELINE DETAILS IN LILLY AND JACK SULLIVAN CASE AS ALLEGED MESSAGES SPARK FRESH CLAIMS

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has entered another sensitive phase as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police released new…

JUST NOW: Investigators Flag Timeline Issues and Re-Examine Key Details in the Disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has taken an unexpected and unsettling turn, according to the latest update released…

A new wave of controversy erupted online this week after the daughter of an NBA legend reportedly came forward with what she described as troubling information involving Stefon Diggs and his relationship with Cardi B.

According to circulating social-media claims, she suggested that Cardi B should reconsider her involvement with the NFL star, citing alleged…

End of content

No more pages to load