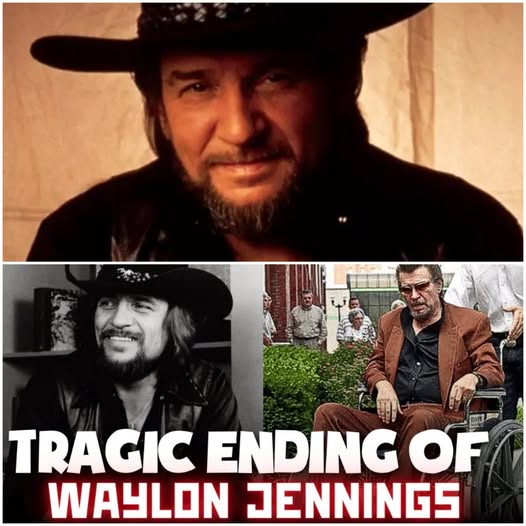

Waylon Jennings wasn’t just a voice in country music; he was a Molotov cocktail hurled at the industry’s polished facade. The Texas-born troubadour, who died in 2002 at age 64, embodied the 1970s “outlaw country” movement, a gritty backlash against Nashville’s slick production machine. Standing tall with Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash, and Kris Kristofferson in the Highwaymen supergroup, Jennings’ bass-baritone growl and defiant swagger turned him into a symbol of rebellion. But peel back the leather and long hair, and you’ll find a saga of addiction, loss, and redemption that nearly derailed his legend.

Born in 1937 in Littlefield, Texas, Jennings cut his teeth as a teen DJ and bass player for Buddy Holly. Tragedy struck early: On February 3, 1959, Jennings gave up his plane seat to J.P. Richardson (The Big Bopper), dooming him to the crash that killed Holly and Ritchie Valens. “The Big Bopper wouldn’t go on without a bass player,” Jennings later quipped darkly, a ghost that haunted him. By the ’60s, he’d landed in Nashville, signed to RCA under Chet Atkins’ watch. But the “Nashville Sound”—overproduced with strings and crooners—clashed with Jennings’ raw edge. He chafed under creative shackles, once smashing a studio console in frustration.

The outlaw era ignited in the early ’70s. Jennings and Nelson, both battling label contracts, demanded autonomy. Their fight birthed hits like Jennings’ 1972’s “Ladies Love Outlaws” and the anthemic “Good Hearted Woman,” co-written with Nelson. By 1976, “Wanted! The Outlaws,” the first platinum country album, featured the duo alongside Cash and Tompall Glaser, selling over a million copies and grossing $10 million on tour. Jennings’ 1977 masterpiece “Ol’ Waylon” spawned No. 1 smashes “Luckenbach, Texas (Back to the Basics of Love)” and “Mammas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys.” His mustache, bell-bottoms, and amphetamine-fueled marathon sessions defined an era when country ditched petticoats for denim and drugs.

Yet glory masked chaos. Jennings’ amphetamine addiction, kickstarted in the ’60s to power through tours, escalated into a daily 500-pill habit by the ’70s. Cocaine followed, fueling paranoia and blackouts. “I was a junkie,” he admitted in his 1996 autobiography. Personal tolls mounted: Three failed marriages before wedding Jessi Colter in 1969, with whom he had a son. Colter’s hit “I’m Not Lisa” was penned amid their turbulent romance. Health crises peaked in 1978 when doctors gave him days to live from overdose complications. Clean in 1984 after a brutal detox—”I woke up sober and stayed that way”—Jennings quit cocaine cold turkey, later ditching amphetamines too.

His influence rippled wide. The outlaw sound paved the way for bro-country and Americana, inspiring Sturgill Simpson and Chris Stapleton. Jennings scored an Emmy for the ’70s TV show “The Dukes of Hazzard” theme, narrated by his gravelly drawl. Inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2001, he leaves 16 No. 1 singles, 60 million records sold, and a net worth once topping $15 million.

Critics hail him as country’s punk rocker. “Waylon made it okay to be real,” Nelson said at his funeral. But whispers persist: Did the plane curse follow him? How close was he to total ruin? In today’s algorithm-driven charts, Jennings’ raw honesty feels revolutionary—a reminder that true rebels don’t just sing about freedom; they live it, scars and all.

As Nashville evolves, Jennings’ legacy endures in dive bars and playlists alike. The man who growled “I’ve always been crazy” proved it, outlasting fame’s temptations to become eternal.

News

Chicago Train Inferno Victim Bethany MaGee: Family’s Heartbreak Deepens as She Battles Gruesome Burns, Clinging to Life Amid Calls for Justice

The flames that engulfed Bethany MaGee on a Chicago Blue Line train didn’t just scar her body—they seared a wound…

Chicago Train Inferno Victim Bethany MaGee: ‘Very Gentle’ Indiana Honors Student Clings to Life After Being Set Ablaze by Repeat Offender

The Windy City’s underbelly has always simmered with stories of random violence, but the Nov. 17, 2025, inferno aboard a…

Anna Kepner Cruise Horror Escalates: Official Homicide Ruling and ‘Bar Hold’ Asphyxiation Ignite Outrage, But Family Demands Full FBI Disclosure

The high-seas tragedy that claimed the life of 18-year-old Anna Marie Kepner—a vibrant Florida cheerleader whose blended-family cruise was meant…

Anna Kepner Cruise Tragedy Unraveled: Asphyxiation ‘Bar Hold’ Confirmed as Cheerleader’s Killer, But Stepbrother Probe Fuels Fury Over Hidden Horrors

The veil has finally lifted on the chilling final hours of Anna Marie Kepner, the 18-year-old Florida cheerleader whose sun-kissed…

Anna Kepner Cruise Death Explodes: Ex-Detective Uncovers Forensics ‘Red Flags’ in Stepbrother Probe

The high-seas nightmare engulfing the Kepner family has veered into thriller territory, with a grizzled ex-detective now poring over leaked…

Florida Cruise Horror Deepens: Stepbrother ‘Doesn’t Remember’ Anna Kepner’s Final Moments, Grandmother Reveals Amid FBI Probe

The sun-drenched family getaway aboard the Carnival Horizon was supposed to be a milestone for the Kepners—a blended brood chasing…

End of content

No more pages to load