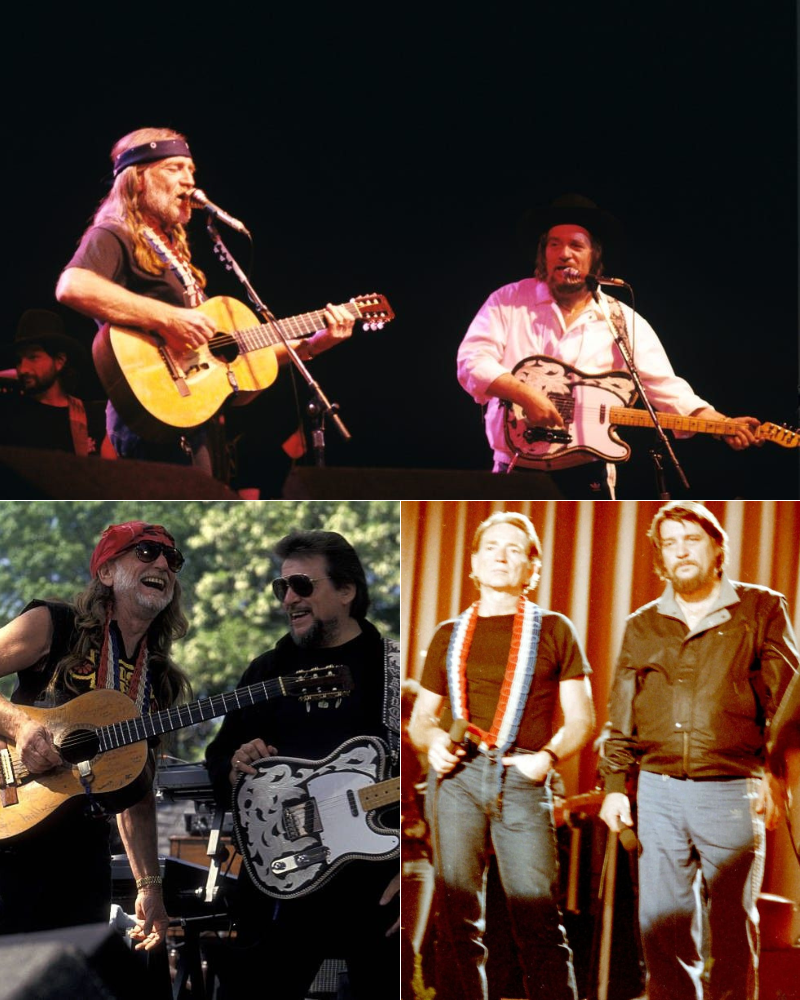

NASHVILLE — In the dusty annals of outlaw country, where rebels like Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson thumbed their noses at Nashville’s polished suits and cookie-cutter crooners, few tracks cut as deep as “Blackjack County Chains.” Recorded for their 1983 duet album Take It to the Limit, this gritty prison ballad isn’t just a song—it’s a raw reckoning with injustice, poverty, and the unbreakable human spirit, delivered by two icons who’d turned the genre on its head. Penned by Red Lane in the late 1960s and first cut by Nelson himself, the tune tells the gut-wrenching tale of a desperate man chained to a Southern chain gang for stealing bread to feed his starving family. No glorification of crime here—just a stark portrait of a system that crushes the forgotten. As Jennings’ gravelly baritone kicks off the verses with unflinching resolve, Nelson’s weathered tenor weaves in like a ghostly echo, their harmonies locking over sparse acoustic strums and wailing steel guitar. “I’m just a prisoner in these old Blackjack County chains,” Jennings growls, his voice dripping with the weight of hard miles, while Nelson’s resigned phrasing adds a layer of haunting finality. Released amid the duo’s peak as the godfathers of the Outlaw movement, the track stands as a timeless testament to their bond—a friendship forged in rebellion that gave voice to the voiceless and reshaped country music forever.

The song’s origins trace back to a simpler, sadder time in Nashville’s underbelly. Red Lane, a journeyman songwriter known for crafting hits like Tanya Tucker’s “What’s Your Mama’s Name,” penned “Blackjack County Chains” in the late 1960s, drawing from real-life tales of Southern poverty and penal cruelty. It first surfaced on Nelson’s 1970 album Willie Nelson and Family, where his lonesome drawl painted the lyrics with poignant restraint: a man “sentenced to hard labor for the rest of my life” after a petty theft born of hunger, forgotten by the world as his “sweet darlin’ baby” waits in vain. The track simmered on the edges of the charts, a cult favorite among die-hard fans who appreciated its unflinching honesty over the era’s saccharine strings. But it was the 1983 Jennings-Nelson duet that elevated it to legend status, transforming a solitary lament into a defiant dialogue between two outlaws who’d battled the Music Row machine together.

By the early ’80s, Jennings and Nelson were more than collaborators—they were brothers in arms, the beating heart of the Outlaw country revolution that exploded in the mid-1970s. Frustrated with Nashville’s formulaic factory—where producers dictated every twang and tear—the pair, along with comrades like Johnny Cash, Kris Kristofferson, and Tompall Glaser, formed the Highwaymen supergroup and carved their own path. Jennings, the long-haired Texan with a rebel yell and a penchant for amphetamines, had already scorched the charts with Honky Tonk Heroes (1973) and Wanted! The Outlaws (1976), the first platinum country album. Nelson, the Red Headed Stranger with braids and a battered Martin guitar, had flipped the script with Shotgun Willie (1973) and Red Headed Stranger (1975), blending jazz, folk, and honky-tonk into a sound that was authentically, unapologetically him. Their duets, starting with 1978’s Waylon & Willie, were magic—raw, road-tested chemistry that turned barroom confessions into bonfire anthems.

Take It to the Limit, released on Columbia Records in January 1983, captured them at their peak: grizzled but golden, trading verses like war stories over tracks like “The Conversation” and the title cut. “Blackjack County Chains” slotted in as the album’s somber centerpiece, a stark contrast to the rowdy romps elsewhere. Clocking in at 3:23, it’s stripped bare—no frills, just Jennings’ Telecaster twang, a mournful pedal steel from Reggie Young, and the duo’s voices intertwining like barbed wire fences. Jennings opens with a baritone that’s equal parts fury and fatigue: “They put me in the jailhouse for stealin’ a loaf of bread / To feed my darlin’ baby and my kids that I must feed.” Nelson picks up the thread in the second verse, his phrasing laced with world-weary wisdom: “The judge he looked me over with a sneerin’ kind of grin / And then he said, ‘Boy, you’re gonna do some time.’” The chorus hits like a chain clank: “I’m just a prisoner in these old Blackjack County chains,” their harmonies swelling with a sorrow that’s almost spiritual, evoking the bluesy ache of Lead Belly’s prison laments but filtered through a country lens.

What elevates the track beyond a simple sob story is its unflinching social commentary—a hallmark of the Outlaw ethos. In an era when country radio peddled escapist fantasies of pickup trucks and honky-tonk honeys, Jennings and Nelson dared to drag the darkness into the daylight: systemic poverty that turns a father’s hunger into felony, a justice system rigged against the ragged, and the quiet despair of being “forgotten like a bad dream” behind bars. Lane’s lyrics, simple yet searing, paint the prisoner not as villain but victim: “They work me from sun up till the settin’ of the sun / And I know that my sweet darlin’ baby waits for me to come.” Jennings, who’d battled his own demons with drugs and the IRS, infused his delivery with hard-won grit, while Nelson—ever the philosopher-poet—added a layer of existential elegance, his voice trailing off like smoke from a lonesome campfire. Produced by Chips Moman at Nashville’s Soundshop Studios, the arrangement keeps it lean: a shuffling bass line from Mike Leech, subtle fiddle fills from Buddy Spicher, and no overdubs to muddy the message. It’s country at its core—honest, harrowing, and human.

The duet’s release came at a pivotal pivot for both men. Jennings was fresh off a career resurgence with Black on Black (1982), shedding his “Hippie Cowboy” skin for a more mature menace, while Nelson was riding high on Always on My Mind (1982), his Grammy-sweeping cover of the Patsy Cline classic cementing his crossover clout. Take It to the Limit peaked at No. 3 on the Billboard Country Albums chart, spawning hits like the title track (a Eagles cover that hit No. 12) and “Blackjack County Chains,” which climbed to No. 25 on the Hot Country Singles. Critics hailed it as a masterclass in minimalism: Rolling Stone called it “the sound of two old gunslingers trading tales by firelight,” while The Village Voice praised the chains track for “turning personal pain into public poetry.” For fans, it was catharsis: bootleg tapes circulated like contraband, and live versions from their joint tours—where Jennings would growl the verses and Nelson croon the chorus—became must-hears at Outlaw reunions.

“Blackjack County Chains” endures as a fan favorite not just for its sonic simplicity, but for the stories it stirs. At Nelson’s 90th birthday bash in 2023, a hologram Jennings “joined” for a virtual duet, the crowd weeping as the opening bars rang out. Kristofferson, before his 2024 passing, called it “the song that chained our hearts together—raw truth in rhyme.” Today, it streams 2 million times monthly on Spotify, spiking during prison reform pushes and economic hard times. Covers abound: Johnny Cash’s estate released a 1990s outtake in 2020, while rising stars like Sturgill Simpson nod to it in live sets. For Jennings, who died in 2002 at 64 after a lifetime of lung battles, and Nelson, still touring at 91 with his signature bandana and battered guitar, the track is a bridge across broken chains—a reminder that outlaw country wasn’t about rebellion for rebellion’s sake, but redemption through revelation.

In an age of Auto-Tune and algorithm anthems, “Blackjack County Chains” stands defiant: a three-minute manifesto of mercy, sung by two men who knew chains of their own. As Nelson quips in a 2018 interview, “We weren’t singing about jail—we were singing about the jails we all carry inside.” For a new generation discovering the Outlaws via TikTok duets and Yellowstone soundtracks, it’s a gateway to grit: proof that the best country comes not from studios, but from souls who’ve stared down the dark. Grab your guitar, pour a whiskey, and let the chains sing—Waylon and Willie would approve.

News

HAZBIN HOTEL SEASON 3 (2026) – When Structure Enters Hell

Season 3 of Hazbin Hotel marks a pivotal evolution for the series. Long defined by chaos, emotional excess, and musical…

MAXTON HALL SEASON 3 (2026) – Fairytale or Control

Season 3 of Maxton Hall enters darker and more complex territory, pushing the story beyond romantic fantasy into a confrontation…

XO, KITTY SEASON 3 (2026) – The Chase Begins With Stillness

Season 3 of XO, Kitty signals a tonal evolution for the series. While previous seasons thrived on youthful chaos, misunderstandings,…

YOUR FAULT: LONDON SEASON 2 (2026) – Love After Trauma

When Your Fault: London returns for Season 2 in 2026, it deliberately slows its pace — not to soften the…

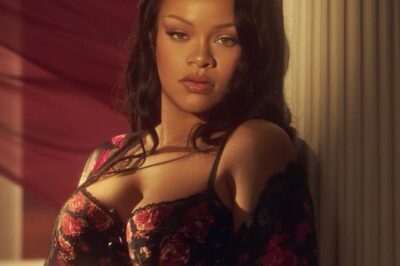

Rumor Swirls: Rihanna Reportedly Appears on Track 3 of A$AP Rocky’s New Album “DON’T BE DUMB” Ahead of Friday Release

As anticipation builds for the release of DON’T BE DUMB, a new rumor has sent fans into a frenzy: Rihanna…

Crans-Montana Fire: Autopsy Reveals Riccardo Minghetti Died From Trampling Injuries, Not Flames

The autopsy of Riccardo Minghetti, one of the victims of the deadly Crans-Montana fire, has revealed a grim and unsettling…

End of content

No more pages to load