6,000 years ago, a ghost people roamed Colombia’s misty highlands—hunter-gatherers with DNA that defies EVERY Native American lineage. 😱 Ancient bones spill their secret: They crossed from Central America, built lives in isolation, then POOF—erased from history without a trace. No descendants, no mixing… just vanished.

What wiped them out—and why does their “extinct” blood echo in today’s chaos? 👉 Tap to unearth the DNA bombshell rewriting the Americas

In a discovery that’s upending the timeline of human migration across the Americas, scientists have sequenced ancient DNA from 21 skeletons unearthed in the misty highlands of the Bogotá Altiplano, revealing a long-lost population of hunter-gatherers who arrived around 6,000 years ago—and then mysteriously vanished, leaving no genetic footprint in modern Indigenous groups. Dubbed the “Checua people” after their high-altitude settlement site, this enigmatic lineage shows no direct ties to North American ancestors like the Clovis culture or to any South American communities today, challenging long-held models of a single, continuous peopling of the continent. The findings, published Thursday in the journal Nature, suggest these early migrants from Central America lived in genetic isolation for millennia before being abruptly replaced by waves of newcomers around 2,000 years ago—sparking debates over what catastrophe, migration, or cultural shift erased them from the gene pool.

The Checua site, a windswept plateau at 2,600 meters (8,500 feet) above sea level in present-day Cundinamarca, has long intrigued archaeologists for its layered history: from nomadic campsites yielding stone tools and charred bones to later Muisca settlements with gold artifacts. But it was the DNA that delivered the shock. Led by geneticist Andrea Casas-Vargas of Universidad Nacional de Colombia, the international team extracted mitochondrial DNA and genome-wide markers from bones and teeth dating from 6,000 to 500 years ago. The oldest samples—two individuals from around 5,800 years before present—carried a unique ancestral signature: a southern Native American branch that diverged early from the main migration wave but showed zero admixture with later groups.

“We expected continuity—a fading echo in today’s Chibchan speakers,” Casas-Vargas said in a press conference at Bogotá’s National Museum of Colombia, her tone a mix of awe and frustration. “Instead, their genes just… stop. No descendants, no blending. It’s as if they were a parallel thread in the Americas’ tapestry, woven in and then snipped clean.” The Checua profile aligns loosely with the earliest South American forays—likely via a coastal or Isthmian land bridge from Central America—but lacks the North American markers seen in Clovis sites or California’s Channel Islands remains. Y-chromosome data (haplogroup Q1b1a, common in Native Americans) hinted at male-line continuity, but broader genomes screamed isolation: elevated levels of rare alleles tied to high-altitude adaptation, perhaps from archaic admixture, but no overlap with Amazonian or Andean lineages.

This isn’t the first “ghost” in America’s genetic attic. Earlier studies flagged the Ancient Beringians in Alaska—isolated Arctic hunter-gatherers from 11,500 years ago with no living kin—and Australasian traces in some Amazonians, hinting at Pacific crossings. But the Checua case is stark: Their disappearance coincides with the Herrera ceramic complex around 3,000 years ago, when migrants from Mesoamerica introduced pottery, maize farming, and Chibchan languages—sweeping aside the old ways without a genetic merger. “It’s replacement, not replacement with mixing,” noted co-author Cosimo Posth of Germany’s Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, who sequenced the genomes in a Tübingen lab. “These newcomers brought tech and tongues, but the locals? Wiped from the record.”

The Bogotá Altiplano’s role as a migration nexus amplifies the mystery. Straddling the Darién Gap’s northern fringe, it’s a natural crossroads: Ice Age hunters funneled south via Panama around 15,000 years ago, splitting into northern and southern Native American clades. Checua fits the southern branch but as an outlier—perhaps a relict group that hunkered down in the Andes’ embrace, adapting to thin air and tubers while coastal waves pushed onward to Peru’s Caral or Brazil’s Serra da Capivara. Artifacts back the isolation: microliths for hunting tapirs and deer, no ceramics until the Herrera influx, and burial practices—flexed bodies in shallow pits—unlike Muisca elites’ urns.

What doomed them? Theories swirl. Climate shifts around 4,000 years ago—drier conditions shrinking highland game—may have starved the plateau, per paleoclimate data from Lake Fúquene sediments. Disease from trade routes, warfare with expanding farmers, or voluntary absorption into dominant groups all loom. “No mass graves, no trauma marks—it’s a silent fade,” said archaeologist Silvia Esperanza Rodriguez of Colombia’s National University, who excavated Checua in 2018. “But the DNA doesn’t lie: They were here, thriving, then ghosts.”

The revelation has ignited a firestorm online and in academia. On X (formerly Twitter), #ChecuaGhost trended with 3.5 million posts by Thursday, blending Indigenous pride with wild speculation. One viral thread from Colombian anthropologist @AndesAncestry dissected the genomes: “Not aliens, not lost tribes—just forgotten kin. Time to rewrite textbooks.” It racked up 1.2 million views, amplified by shares from podcaster Joe Rogan: “Another layer peeled off the Americas’ onion—makes you wonder what else we’re missing.” YouTube explainers like “Ancient DNA Shock: Colombia’s Vanished People” from History Unboxed hit 2 million watches overnight, while Reddit’s r/Archaeology buzzed with threads tying Checua to Amazonian “ghost” signals in 2022 Cell papers.

Indigenous voices add poignant weight. The Muisca Confederation, descendants of Altiplano farmers, issued a statement hailing the find as “ancestral validation—not erasure, but reclamation.” Leader Rubén Darío Rodríguez told local media: “We’ve always known our lands hold secrets. This proves the plateau birthed nations, even if some faded like morning mist.” But sensitivities run deep: Colombia’s 2021 constitutional ruling mandates Indigenous consent for genetic studies, and some Chibchan groups in Panama decry “colonizer science” commodifying DNA.

Broader implications ripple through migration lore. The Americas’ peopling—once a tidy Beringian funnel 15,000 years ago—now sprawls with branches: A 2023 Live Science model posits three basal splits, including “unsampled ghosts” like Checua, detected only in Mixe genomes from Mexico. Harvard’s David Reich, whose 2022 Cell study flagged two “unknown” South American clades, called it “a mosaic, not a line—each dig chips away at the monolith.” Critics like Kim TallBear, a Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate citizen and Indigenous STS scholar, warn in Native American DNA: “Genes don’t define belonging—relations do. This ‘vanished’ label risks othering living kin.”

Fieldwork ramps up: A joint Colombian-German expedition returns to Checua next spring, armed with LiDAR for hidden settlements and aDNA kits for more bones. UNESCO eyes the site for World Heritage status, alongside Tiwanaku’s ruins. For now, the ghosts whisper through isotopes: Elevated strontium in Checua teeth points to local diets—quinoa, guinea pigs—untouched by outsiders until the Herrera wave.

In a continent scarred by conquest—Columbus’s 1492 “discovery” erasing millions—this find humanizes the prelude. The Checua weren’t conquerors or victims; they were adapters, eking life from thin air until the winds shifted. Their vanishing? A cautionary echo in today’s migrations—climate refugees, border walls. As Casas-Vargas put it: “They remind us: Humans are threads, not roots. Pull one, the weave frays.”

The Nature paper drops full genomes online Friday; Bogotá’s museum hosts a free exhibit through December. In the Altiplano’s eternal fog, a vanished voice endures—proof the Americas’ story is far from told.

News

The victim, identified as Alexander E. Sanchez-Montilla, suffered multiple gunshot wounds to both legs around 6 p.m

🚨 FACEBOOK MARKETPLACE NIGHTMARE: A simple car-buying meetup turns into a BLOODBATH – 41-year-old dad Alexander Sánchez-Montilla steps into a…

The remaining three fatalities were professional guides from Blackbird Mountain Guides: Andrew Alissandratos

🚨 HEARTBREAK IN THE MOUNTAINS: Six incredible moms—wives, best friends, passionate skiers—buried alive under a massive avalanche the size of…

Duxbury Mom Lindsay Clancy Makes First In-Person Court Appearance Ahead of Murder Tria

🚨 SHOCKING COURTROOM MOMENT: The mom who stra-ngled her three babies—Cora (5), Dawson (3), and tiny Callan (8 months)—finally wheeled…

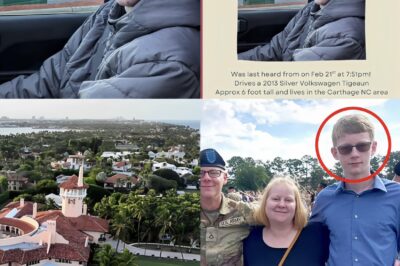

Armed Intruder Fatally Shot at Mar-a-Lago Perimeter: 21-Year-Old North Carolina Man Identified as Austin Tucker Martin

🚨 BREAKING: A 21-year-old “quiet” golf-loving kid from North Carolina drives 700+ miles overnight… armed with a SHOTGUN and a…

Tragedy in Ocala: U.S. Coast Guard Veteran and Family of Four Found Dead in Suspected Carbon Monoxide Poisoning

🚨 IMAGINE THIS: He calls his mom that afternoon, laughing, planning dinner… “See you soon, Ma.” THAT NIGHT, silence. A…

The disappearance of 36-year-old Shana M. Umbreit from this small Lake Huron community has ended in tragedy

A small-town Michigan mom vanishes after a late-night gas station stop. Three weeks later, her body turns up in a…

End of content

No more pages to load