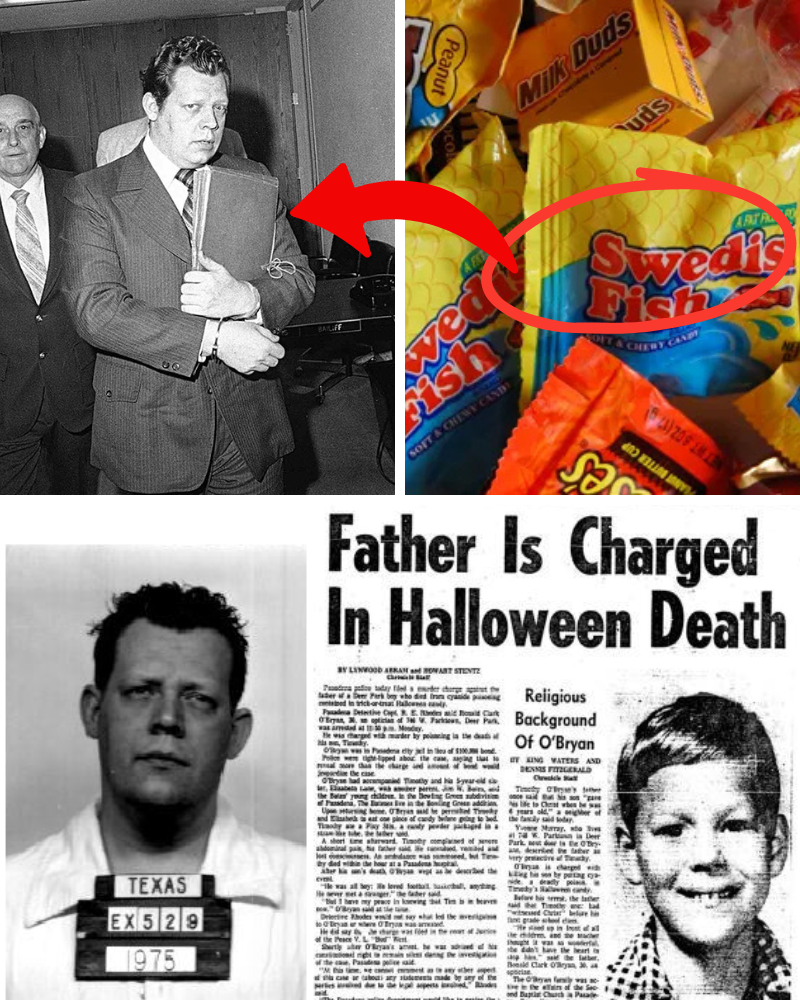

Halloween 1974 was supposed to be like any other in the quiet Houston suburb of Deer Park, Texas—a night of flickering jack-o’-lanterns, costumed kids darting door-to-door, and parents sorting through hauls of chocolate bars and gummy treats under porch lights. But for 8-year-old Timothy O’Bryan, dressed as a caped crusader that rainy evening, it became a fatal finale. After returning home from trick-or-treating with his father, Ronald Clark O’Bryan, and a group of neighborhood children, Timothy eagerly sampled a giant Pixy Stix from his bag. Within minutes, he was vomiting and convulsing. By 10:30 p.m., the boy was dead—poisoned by potassium cyanide laced into the candy tube. What followed was a investigation that exposed not a stranger’s malice, but a father’s cold-blooded scheme, forever altering how America celebrated the holiday.

The case, which gripped headlines for months, revealed O’Bryan as the architect of his son’s demise. Dubbed “The Candy Man” and “The Man Who Killed Halloween” by tabloids, the 30-year-old optician had tampered with five oversized Pixy Stix tubes, replacing the top inches of powdered sugar with enough cyanide to kill several adults. His motive? Crushing financial debt—over $100,000 from failed business ventures and a string of 21 firings in a decade—and the lure of $40,000 in recently purchased life insurance on Timothy. But O’Bryan didn’t stop at one victim. To cloak his crime, he distributed the deadly treats to his own 5-year-old daughter, Elizabeth, and three neighborhood kids, including the sons of family friend Jim Bates. By sheer luck—or divine intervention, as some later called it—none of the others consumed theirs. One boy even tried sucking on his but stopped, stymied by the staple O’Bryan had crudely used to reseal the tube.

Pasadena police, initially baffled by the rarity of a poisoning via trick-or-treat candy, launched a frantic retracing of the group’s route. The evening had started innocently enough: O’Bryan, a church deacon with a reputation for piety, joined Bates and their children for dinner at the Bates home in nearby Pasadena. Around 7 p.m., as a light drizzle fell, the dads chaperoned the kids through the streets—ghosts, witches, and superheroes giggling amid the rustle of plastic bags. At one dimly lit house on Winchester Street, no one answered the door. The impatient children pressed on, but O’Bryan lingered. When he caught up minutes later, he triumphantly produced the five Pixy Stix, claiming the mysterious occupant had cracked the door and handed them out as “special treats.” He doled one to each child in the group, pocketed the fifth for Elizabeth, and later slipped it to a 10-year-old boy from their South Lawn Methodist Church congregation who knocked on their door later that night.

Back home in Deer Park, O’Bryan allowed his children one piece of candy before bed. Witnesses later testified that Timothy hadn’t picked the Pixy Stix on his own—O’Bryan suggested it, even helping his son pour the powder into his mouth when it wouldn’t flow easily. “It tastes funny,” Timothy reportedly said, grimacing at the bitter tang. His father dismissed it, urging him to chase it with Kool-Aid. The boy complied, retiring to his room in his superhero costume. Soon after, screams pierced the quiet house. Timothy’s stomach heaved; his small body seized in agony. Paramedics rushed him to Texas Children’s Hospital, but the cyanide—25 times a lethal dose for an adult—had already ravaged his system. He was pronounced dead at 10:35 p.m.

The next morning, as news of the “poisoned Halloween candy” spread like wildfire, panic engulfed Houston. Parents dumped bags of treats into police stations; schools canceled costume parades; neighborhoods formed candy-inspection patrols. Detectives, led by Sgt. J.S. “Jim” Norman, tested Timothy’s haul and zeroed in on the Pixy Stix. Retrieving the other four tubes proved harrowing—Bates’ son had clutched his uneaten one while sleeping, a staple glinting under the bedside lamp. Lab results confirmed the nightmare: all five contained cyanide granules. But who bought the poison? O’Bryan had, purchasing 10 ounces of sodium cyanide from a Houston chemical supply firm two weeks earlier, under the pretense of rat extermination at his workplace. Receipts and employee testimonies placed him there, quizzing clerks on dosage lethality.

Suspicion pivoted to O’Bryan swiftly. Neighbors recalled his odd behavior: lingering too long at houses, his excitement over the “rare” Pixy Stix seeming forced. Bates, the unwitting escort, grew uneasy when O’Bryan pressed him not to mention the mysterious house. Financial forensics painted a damning portrait—the O’Bryans were drowning in debt from a botched plastics molding business and unpaid loans. Just months prior, O’Bryan had doubled down on life insurance: $10,000 on Elizabeth, $40,000 on Timothy, with himself as beneficiary. He even bragged to co-workers about “big plans” post-payout, including a family trip to Disney World. During the investigation, O’Bryan’s wife, Daynene, shattered the facade, testifying that her husband had forced Timothy to eat the candy—not the boy’s choice, as he’d claimed. “He wanted that money more than anything,” she told jurors, her voice steady despite the betrayal.

O’Bryan’s arrest came on November 5, 1974, five days after Timothy’s death. Pasadena erupted in outrage—reporters swarmed the modest brick home on Luella Avenue; protesters chanted outside the jail. His defense leaned on urban legends: the bogeyman of razor-laced apples or poisoned treats, a myth that had circulated since the 1950s but lacked a single verified case until now. O’Bryan took the stand, tearfully denying involvement, blaming a shadowy figure at the unlit house. But the jury—nine women, three men—saw through it. After six hours of deliberation in June 1975, they convicted him of capital murder. “Guilty,” the foreman intoned, sealing his fate. Judge Wallace Moore sentenced him to death, calling it “a crime against humanity itself.”

The trial, held in Houston’s Harris County Courthouse, drew national scrutiny. Prosecutors Mike Hinton and Erwin Ernst paraded 80 witnesses: chemists detailing the cyanide’s industrial sourcing, insurers confirming policy dates, even O’Bryan’s sister recounting his pre-Halloween mutterings about “easy money.” Daynene’s testimony proved pivotal—she’d overheard him scheming, piecing together his cyanide inquiries from work friends. O’Bryan, unrepentant, smirked through much of it, but crumbled when Elizabeth, then 5, was mentioned. The girl, spared only by her disinterest in the “weird straw candy,” grew up under protective custody, her innocence a stark counterpoint to her brother’s fate.

Appeals dragged on for nearly a decade, O’Bryan insisting innocence from death row at Huntsville Unit. He filed writs citing jury bias, ineffective counsel—even a biblical argument against execution. But Texas law prevailed. On March 31, 1984, at 12:01 a.m., the state strapped him to the gurney. His last words? A rote prayer: “I want to thank you for your love and support. I forgive those who wronged me.” Witnesses, including Hinton, watched as lethal injections coursed through. “He died as coldly as he lived,” Hinton later reflected. O’Bryan’s body was cremated; no family claimed it.

The ripple effects extended far beyond Texas. Dubbed “The Death of Halloween” by Time magazine, the case ignited a cultural sea change. Pre-1974, trick-or-treating was a freewheeling ritual—kids roaming unsupervised till 10 p.m., sorting candy by flashlight. Post-Timothy, fear gripped suburbs nationwide. The Consumer Product Safety Commission issued warnings; cities like Los Angeles banned door-to-door collecting. By 1975, “X-ray your candy” became parental gospel—hospitals reported surges in “poison checks.” Urban myths proliferated: needles in Snickers, LSD on lollipops. Though experts like Joel Best, author of Threatened Children, later debunked stranger-danger poisonings as “moral panic,” the damage stuck. Today, 70% of parents inspect treats, per a 2023 National Safety Council survey, and organized trunk-or-treats outnumber street hauls in many towns.

For the survivors, scars linger. Daynene remarried, raising Elizabeth in seclusion; Bates, haunted by the near-miss, became a vocal advocate for child safety laws. Timothy’s grave in Houston’s Forest Park Cemetery draws quiet pilgrims each October 31—flowers, notes reading “Rest easy, little hero.” The O’Bryan home sold quickly, razed for a vacant lot now overgrown with weeds.

Fifty years on, as ghosts and goblins reclaim streets, the Candy Man’s shadow endures—a cautionary specter in orange and black. It reminds that true horror hides not in costumes, but in the hearts of those we trust most. In a holiday built on playful frights, Ronald O’Bryan’s legacy is the one that refuses to fade.

The Crime Desk reached out to Bates family descendants for comment; a spokesperson declined, citing privacy. Daynene O’Bryan could not be located.

News

Rihanna Responds to a Fan Saying, “They Saying It’s 2016, Rih”: What Her Viral Reply Really Means

When a fan recently commented, “They saying it’s 2016, Rih,” few expected Rihanna to respond. She often ignores random online…

Rihanna’s Unmatched Face Card: How One Look Became a Cultural Phenomenon

Few celebrities command attention the way Rihanna does. Across red carpets, candid street photographs, and unfiltered social media moments, one…

400,000 FRANCS FOR RELEASE: PROSECUTORS SEEK BAIL FOR OWNERS AFTER DEADLY CRANS-MONTANA NEW YEAR FIRE

Prosecutors in Sion have requested a total of 400,000 Swiss francs in bail to grant provisional freedom to Jacques and…

📰 RCMP RELEASES NEW TIMELINE DETAILS IN LILLY AND JACK SULLIVAN CASE AS ALLEGED MESSAGES SPARK FRESH CLAIMS

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has entered another sensitive phase as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police released new…

JUST NOW: Investigators Flag Timeline Issues and Re-Examine Key Details in the Disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has taken an unexpected and unsettling turn, according to the latest update released…

A new wave of controversy erupted online this week after the daughter of an NBA legend reportedly came forward with what she described as troubling information involving Stefon Diggs and his relationship with Cardi B.

According to circulating social-media claims, she suggested that Cardi B should reconsider her involvement with the NFL star, citing alleged…

End of content

No more pages to load